S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

06 Mar, 2025

By Zack Hale

| An aerial view of an Amazon Web Services datacenter in Ashburn, Virginia, taken July 17, 2024. Source: Nathan Howard/Getty Editorial via Getty Images. |

Harvard University legal scholars are offering key recommendations for how utility regulators can shield ratepayers from hidden costs as large technology companies look to secure new power supplies and related grid upgrades for their rapidly expanding datacenter operations.

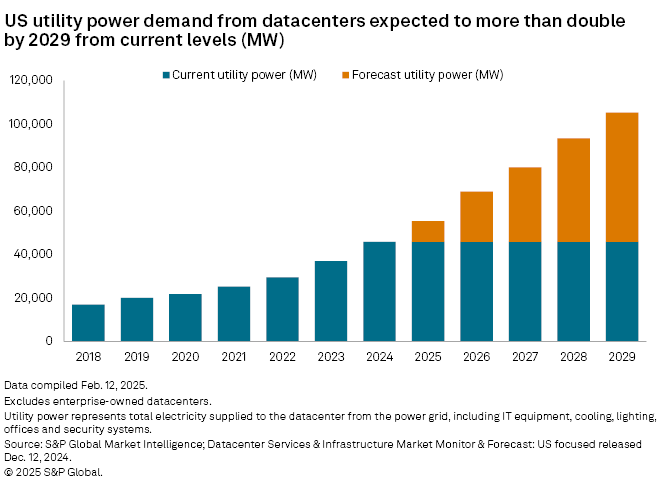

With US power demand from datacenters projected to double from current levels by 2029, utilities already have multiple ways to subtly embed datacenter-related costs in residential rates, according to a paper published March 5 by Harvard Law School's Environmental and Energy Law Program.

"Attracting datacenters is now this big competition among utilities, so we wanted to figure out the ways that utilities may be funding discounts or otherwise shifting the costs of datacenter energy and infrastructure to everyone else," Ari Peskoe, director of Harvard's Electricity Law Initiative and co-author of the paper, said in an interview.

Datacenter cost-shifting

One popular method of cost-shifting involves offering special, or "secret," contracts to datacenter customers, Peskoe and co-author Eliza Martin, a legal fellow at Harvard, explained in the paper.

Such contracts typically offer a price lower than the utility's cost to serve the customer. To recoup the forgone revenue, utilities will seek to raise rates for residential customers in subsequent rate cases, the paper said.

Peskoe and Martin identified 40 publicly available state public utility commission proceedings through their research in which regulators frequently approved special contracts "in short and conclusory orders."

"Challenging the utility's analysis is costly and time-intensive, and staff may not have the resources to provide robust analysis," the authors noted. "As a result, we find that many PUC orders approving special contracts simply conclude that the proposed contract is reasonable without meaningfully engaging with the proposal."

Utilities can also shift costs by exploiting gaps between federal and state regulation, the paper said.

As an example, the paper cited the PJM Interconnection LLC's $5.1 billion regional transmission expansion plan.

The mid-Atlantic grid operator's plan was approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in April 2024 over a protest from the Maryland Office of People's Counsel, the state's ratepayer advocate. The Office of People's Counsel had argued that PJM's plan would inappropriately charge Maryland residents for transmission upgrades needed to accommodate datacenter growth in Northern Virginia, an area that has seen a surge in datacenter development tied to state tax subsidies.

FERC ultimately approved PJM's proposal to allocate roughly half the cost of the plan to Northern Virginia, with Maryland ratepayers funding approximately 10%. However, the Harvard paper noted that investor-owned utilities in both states include more than half of their regional transmission costs in residential rates.

"Thus, in both states, residential ratepayers are paying the majority of regional transmission costs that are tied to datacenter growth," the paper said.

Meanwhile, datacenter customers can reduce what are known as "demand" charges by curbing their electricity use when the power system is at peak use — typically for just a few hours out of the operating year. This can shift regional costs for the system onto other customers who are unable to reduce their demand in the same way, the paper said.

The authors further noted that colocation models — where a datacenter receives behind-the-meter power from a nearby generator such as a nuclear power plant — can increase wholesale power market prices for other customers in the region. The Harvard researchers cited a recent warning from PJM's independent market monitor that the 13-state region would see "extreme" price impacts if all of its nuclear power plants attract colocated customers.

"Energy prices would increase significantly as low-cost nuclear energy is displaced by higher cost energy," the market monitor warned, adding that PJM capacity prices would also increase as supply is reduced through behind-the-meter arrangements.

Solutions for regulators

The Harvard paper offered four primary recommendations to protect consumers from hidden datacenter costs.

To begin, the authors said state regulators should establish more rigorous guidelines for reviewing special contracts. The Kentucky Public Service Commission, for example, in 2023 rejected a proposed special contract for a cryptocurrency miner after finding that the agreement did not shield ratepayers from the customer's power costs, the paper noted.

State regulators could also go further by requiring utilities to offer standardized terms and conditions for future datacenter customers, the authors said.

"This holistic and uniform approach ends the race-to-the-bottom competition that incentivizes utilities to attract customers by offering hidden discounts paid for by other ratepayers," they said.

At a broader level, state legislators could require datacenter customers to contract with competitive power suppliers, the paper suggested.

"Requiring the datacenter to contract with a competitive supplier rather than with the utility would ensure that all stranded costs associated with the generation are allocated between the datacenter and its supplier," the authors said.

Finally, Peskoe and Martin floated the idea of state-approved "energy parks," where sufficient on-site generation is available to power large datacenter operations. Locating energy parks outside of for-profit utilities' service territories could shield customers from hidden datacenter costs, the paper said.

"Some of these growth numbers are so astounding that they raise all kinds of challenges," Peskoe said in the interview. "Not just in setting the rates, like we're focused on in this paper, but all the things you need to do to build this infrastructure."

Peskoe noted that one of the paper's main conclusions is that state regulators are generally reluctant to veto utility contracts with large tech companies. "Putting aside all of the challenges for reform, some of these deals certainly have a lot of momentum behind them," he said.