INTRODUCTION TO PREFERRED STOCKS

What Are Preferred Stocks?

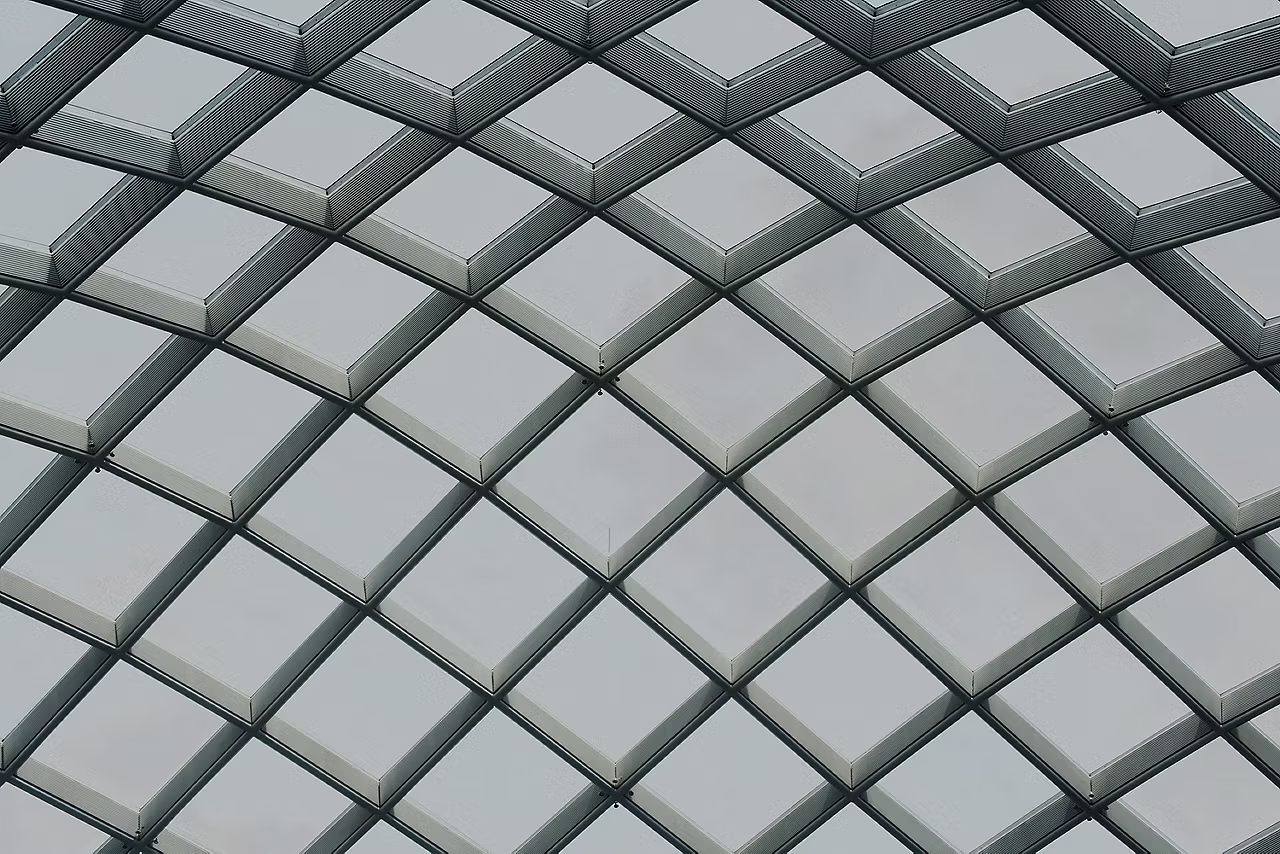

Preferred stocks are hybrid securities, blending characteristics of stocks and bonds. They sit between common stocks and bonds in a company’s capital structure, thus having a higher claim on a company’s assets and earnings than common stocks, while having a lower claim than bonds (see Exhibit 1).

Like common stocks, preferred stocks represent ownership in a company and are listed as equity in a company’s balance sheet. However, certain characteristics differentiate preferred stocks from common stocks. First, preferred stocks provide income to investors in the form of dividend payments, typically providing higher yields than common stocks. Second, preferred shareholders lack voting rights, resulting in less influence on corporate policy. While common stock shares offer investors the potential for share price and dividend increases, investors generally look to preferred stocks for their high-yielding, stable dividend payments.

Preferred stocks are issued at a fixed par value, similar to bonds, with most paying a scheduled fixed dividend. Preferred stocks are rated by independent credit rating agencies. The rating is generally lower than bonds since preferred stocks offer fewer guarantees and have a lower claim on assets. While a company risks defaulting if it misses a bondcoupon payment, it can withhold a preferred dividend payment without facing default risk.[1]