Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Oct, 2022

By Brian Scheid

The U.S. government bond market is flashing strong signals of an imminent recession.

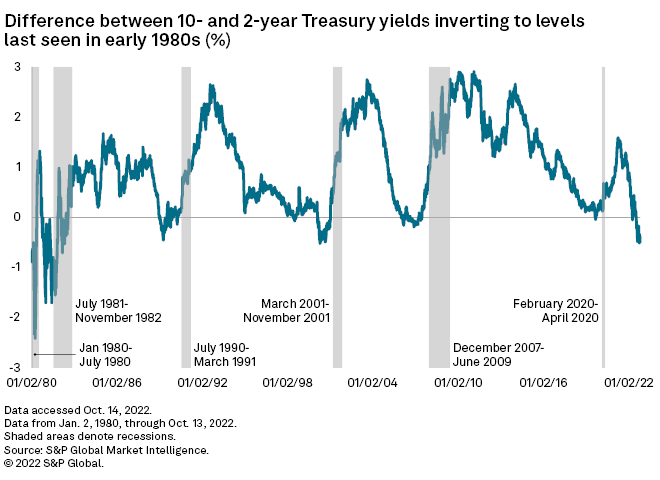

Key portions of the Treasury yield curve are nearing inversion or inverting to degrees not seen since the early 1980s. As inflation continues to soar to four-decade highs and the domestic labor market remains stubbornly tight, shorter-duration bond yields are expected to climb further and faster than longer-dated yields, creating further inversion and increasing the likelihood of a deep recession.

10 minus 2

After the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported on Oct. 13 that a key inflation measure had reached its highest level in more than 40 years, the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note settled 50 basis points lower than the 2-year bond. This inversion — in which the shorter duration yield is higher — was a 13-bps increase from Oct. 12 and a 169-bps reversal from one year ago when the 10-year was 119 basis points above the 2-year.

The inversion is now at levels last seen in 2000 and is expected to climb further, potentially nearing levels last seen in the early 1980s. In March 1980, the 2-year yield rose 241 basis points above the 10-year.

Another predictor

The yield curve has inverted before every recession for the past 50 years, although not every inversion has preceded a recession.

Rather than using the difference between the 10-year and 2-year yields, some economists prefer the difference between the 10-year and 3-month yields, which they view as a better predictor of a coming recession.

The gap between those yields settled at 18 bps on Oct. 13, compared to 151 basis points a year ago. The difference between the 10-year and 3-month yield last inverted in February 2020, when the global pandemic began and the U.S. was in its last recession.

A flatter curve

Over the past year, the yield curve has flattened, with short-duration yields surging as the Fed has raised rates after two years of keeping its benchmark federal funds rate near 0% in response to the pandemic.

The 1-year Treasury yield, for example, has jumped 435 bps over the past year and the 2-year yield has climbed 410 bps. The 10-year and 30-year yields have risen considerably less, increasing by 241 and 192 bps, respectively.

More hikes

The inversion has increased as expectations for additional rate hikes have grown.

The Fed has boosted rates by 300 bps since March, including three straight jumps of 75 bps at their last three meetings. The central bank is expected to raise rates by another 75 bps at its November meeting.

As of Oct. 13, the majority of the futures market was forecasting the Fed will increase rates by an additional 175 bps by February 2023, according to the CME FedWatch Tool, which measures investor sentiment in the Fed funds futures market.

Nearly 40% of the market expects the Fed to hike the federal funds rate to above 5%, a level it has not been at since 2007.