Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

18 Oct, 2022

By Sanne Wass

Climate stress tests are playing a growing role in bank supervision as more regulators and prudential authorities embrace this tool to assess banks' resilience to environmental risks.

The U.S. Federal Reserve announced last month that it would conduct a climate scenario analysis involving Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc., Goldman Sachs Group Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co., Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo & Co.

More than 100 eurozone banks have already taken part in the European Central Bank's supervisory climate risk stress test this year, while seven U.K. lenders were assessed in the Bank of England's Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario.

Elsewhere, regulators and prudential authorities in Canada, China, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, Mexico, Peru and Chile are accelerating their climate risk assessments through stress tests, according to S&P Global Ratings research released Oct. 3.

The tests, however, face challenges around data, scenarios and designs, meaning regulators will be careful in how they use the results for now.

Here are four key lessons learned from climate exercises so far.

Losses manageable but underestimated

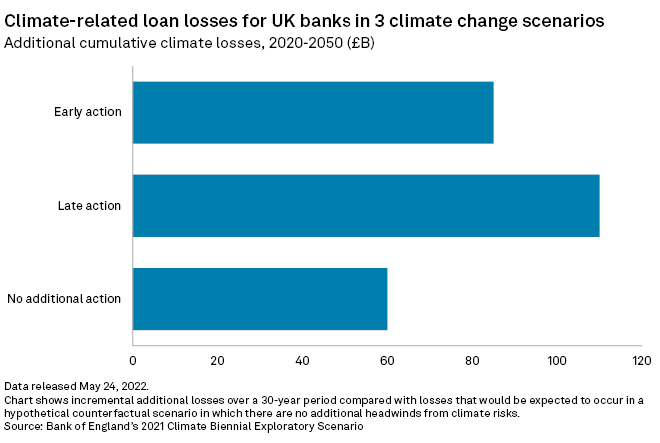

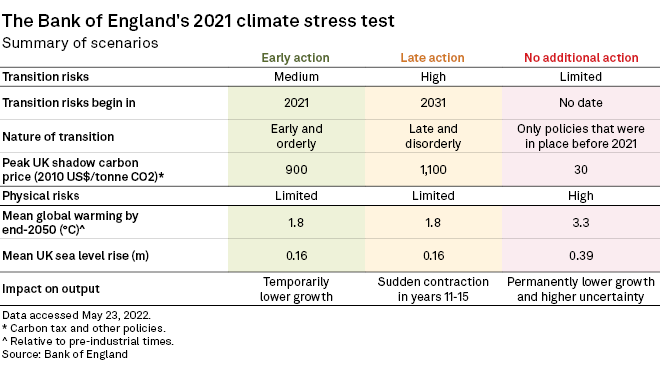

Some climate stress tests have disclosed quantitative results showing the potential impact of climate risk on bank losses. In the eurozone, 41 banks projected aggregate additional climate-related losses of about €70 billion over a three-year period, while in the U.K. seven lenders forecast up to £110 billion in loan losses over 30 years.

In both cases, the impact is "very manageable," and losses are low compared with those recorded in traditional financial stress tests, which assess banks' ability to cope with financial or economic shocks, said Fernando de la Mora, managing director at consulting firm Alvarez & Marsal, who advises banks on climate stress testing.

However, climate stress tests are likely to underestimate future losses, said Francesca Sacchi, associate director in S&P Global Ratings' financial institution team. Apart from data limitations, most exercises used "relatively mild assumptions," she said, adding that potential second-round effects on gross domestic product not captured by the scenarios could exacerbate the impact on losses.

Furthermore, climate stress tests have focused only on a portion of the banks' assets, Sacchi said. Exposures within the scope of the ECB's exercise, for example, only accounted for about one-third of total exposures of the 41 banks.

Data gaps a major challenge

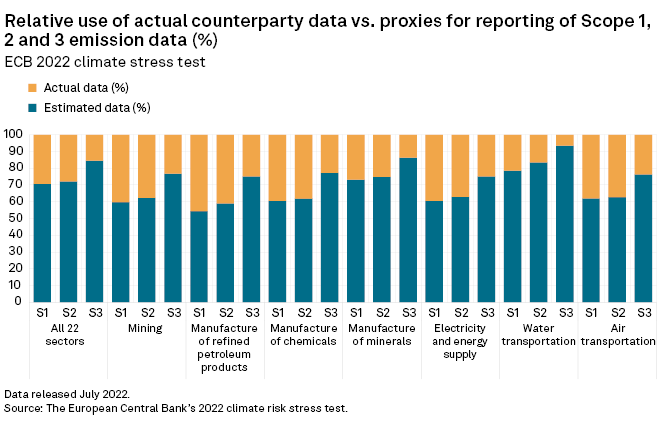

Lack of data was a key challenge in the climate stress tests, and banks relied heavily on proxies to make projections.

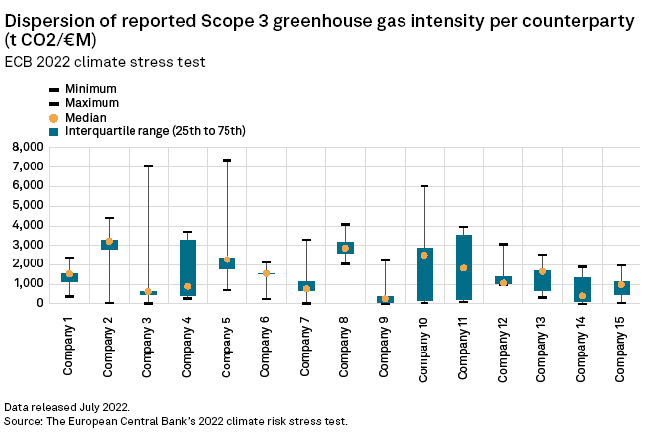

The ECB in its results in July reported that banks made widespread use of proxy data to compile key data points for Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions as well as energy efficiency ratings for mortgage and real estate exposures. This led to high dispersion of the data reported by banks, even for the same corporate counterparties.

In one example, one bank reported Scope 3 emissions intensity for a corporate client of more than 7,000 tons CO2/€ million revenue, while another bank reported this number at zero for the same counterparty.

In the U.K., banks' estimated loss rates differed "substantially" for the same corporate customers, according to the Bank of England, which released its results in May. The most conservative estimates for losses were around 10 times higher on average than the least conservative, it found.

"The tests display considerable gaps in models and data," said de la Mora. "There's a big discrepancy in terms of the results."

The good news is the exercises have driven better awareness of data gaps among banks and "served as a catalyst to accelerate the collection of climate change information from banks' clients and methodology developments," according to Wim Mijs, CEO of the European Banking Association.

Chithra Namboodiri, global head of wholesale environmental, social and governance risk analytics at HSBC Holdings PLC, said there was "a lot of effort involved to make sure we're building the right capabilities" as part of the Bank of England exercise, which enabled the bank to build its climate data further.

HSBC started engaging with internal stakeholders, including frontline, portfolio management and risk teams, to gather data where it was not available from external providers. This has helped to improve the bank's modeling, Namboodiri said, speaking at an event hosted by S&P Global Sustainable1 on Sept. 29.

Test designs impact results

Climate stress test designs have similarities across jurisdictions. For example, most directly use scenarios published by the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System, or NGFS, or an adjusted version of the scenarios, said Alban Pyanet, a partner at Oliver Wyman who works with global banks on climate stress testing. In other areas, designs vary, including the types of risks assessed and the level of prescription set by the regulators, he said.

"We have to keep in mind all those design decisions when it comes to interpreting the results," Pyanet said.

In measuring the physical risk impact on real estate, for example, the ECB provided the value of the shock based on property characteristics and location, while the Bank of England asked banks to estimate this shock themselves, Pyanet said.

"While a higher level of prescription by the regulator ensures better comparability of the results, giving institutions more flexibility often allows them to explore the methodologies and understand the risks in more detail," he said.

While the ECB and Bank of England tested banks against both physical and transition risks, other jurisdictions have explored only one of them, according to Sacchi. Physical risks are those that arrive from climatic events, such as wildfires, storms and floods, while transition risks result from policy action taken to drive the transition toward a low-carbon economy.

Not a traditional "stress test" — for now

The climate exercises are not stress tests in the traditional sense in that they are not used to set capital requirements for individual banks, said Pyanet. For that reason, some regulators have decided not to describe their exercises as a "stress test."

In contrast to traditional stress tests and transparency exercises, authorities have also opted to disclose aggregate results rather than firm-level disclosures. This makes it difficult for credit analysts to leverage the information provided in their work, said Nicolas Hardy, deputy head of financial institutions at Scope Ratings.

The Bank of England has named its climate exercise a "Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario," while the U.S. Fed calls its upcoming test a "pilot climate scenario analysis."

The ECB has described its "climate risk stress test" so far as a "learning exercise for banks and supervisors alike." The results will be integrated into the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process, or SREP, but in an indirect and qualitative way only. SREP assesses the way a bank deals with risks and helps supervisors determine Pillar 2 capital requirements or guidance for an institution.

ECB board member Frank Elderson in a June speech emphasized that the "typical number-crunching" to assess the impact of stresses is only one part of the overall exercise. "At this stage, the fact that banks provide proof of their climate stress testing capabilities is as important as the results of the test," he said.

In time, however, climate scenario analyses are expected to play an increasingly important role in bank supervision. "We did not come up yet with quantitative capital requirements, but that will come eventually," said Patrick Amis, director-general at the ECB, speaking at an S&P Global Ratings webinar Oct. 4.

S&P Global Ratings anticipates that supervisors will "fine-tune their stress tests over time" and provide more detailed quantitative measures of the climate-related risks at system and individual bank levels.

Alvarez & Marsal's de la Mora expects European banks will start to face climate-related Pillar 2 add-ons in the next two to three years.