Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Sep, 2021

By Brian Scheid and Zoe Sagalow

The political impasse over raising the federal debt limit could rattle markets and push back the Federal Reserve's plans to tighten post-pandemic monetary policy.

The federal government must raise its $28.4 trillion debt limit soon or suspend it in order for the U.S. to be able to pay its bills. The Treasury Department estimates the limit could be reached as soon as October. Congressional Republicans plan to oppose any debt ceiling increase in order to slow President Biden's economic agenda.

If the partisan impasse drags on until then, the odds of a government shutdown increase and the threat of a downgrade to the U.S. credit rating grows, said Gennadiy Goldberg, a senior rates strategist at TD Securities.

"While we view the problem of addressing the debt ceiling as largely a political issue, the fight over how the ceiling will be addressed increases the odds that negotiations go down to the wire, making markets nervous," said Goldberg.

In a Sept. 8 letter to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and other congressional leaders, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned that further delaying a raise to the debt limit could harm consumer confidence, increase borrowing costs and damage the U.S. credit rating.

"A delay that calls into question the federal government's ability to meet all its obligations would likely cause irreparable damage to the U.S. economy and global financial markets," Yellen wrote.

Then vs. now

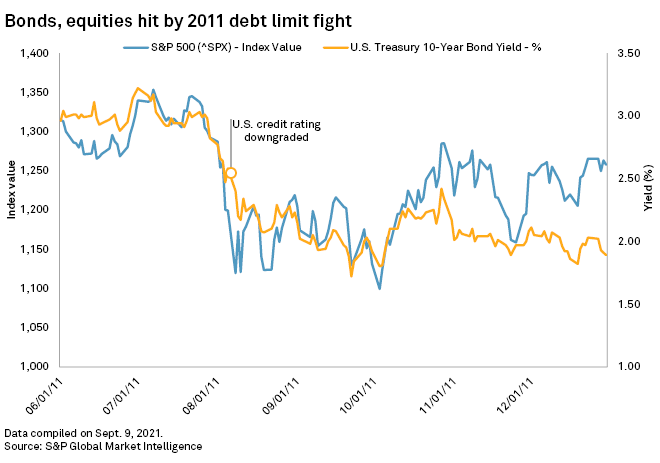

Tom Essaye, a trader and founder of financial research firm The Sevens Report, said the potential market response could look like August 2011, when a debt ceiling standoff led Standard & Poor's to downgrade the U.S. credit rating for the first time. The S&P 500 plunged nearly 7%, and the yield on the benchmark U.S. Treasury 10-year bond fell over 40 basis points in response to that event.

Essaye believes that with stocks at high valuations, the debt ceiling debate may not derail the ongoing U.S. stock market rally, but it could cause a sizable correction.

"I think in a market that's stretched, that doesn't have a lot of backing at these fundamental levels, if you get some sort of serious scare, it could take 5% to 10% out of the S&P 500 pretty quick," Essaye said.

Essaye said that while few expect the debt limit to be breached, investors will likely flood into bonds, sending yields on the 10-year bond nearly 20 points lower. Bond yields move inversely to prices, and a declining yield indicates a rise in demand.

"Everyone thinks this is brinkmanship and gamesmanship, but they still would want the security of bonds," Essaye said.

Derek Tang, a co-founder and president at LH Meyer Inc. and an economist, said that Treasury bills expiring in late October or early November, when the debt limit could be breached, are trading at higher yields than those with maturity dates before and after.

"Investors are demanding a higher return to hold them, to account for their higher risk," Tang said.

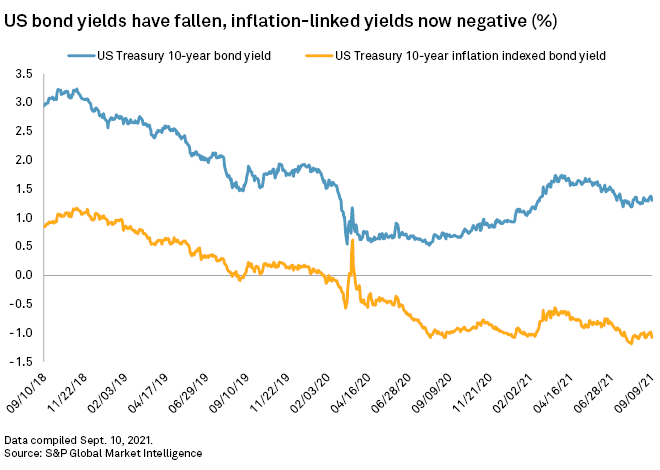

The potential impact on bonds may look far different than in 2011, largely due to the fact that yields are already relatively low, said Althea Spinozzi, a senior rates strategist with Saxo Bank. Bonds are already expensive, and real yields, which take inflation into account, are deeply negative.

Taper conundrum

In addition, the flight to bonds could be affected by the Fed's plans to taper its $120 billion monthly purchases of Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities, which analysts believe will begin late this year or early next year.

"The debt ceiling issue could derail their agenda completely and cause tapering to be postponed first, contributing to low U.S. Treasury yields," said Spinozzi. "But afterwards the Fed will need to taper more aggressively and eventually hike interest rates causing much more volatility than intended."

But economists and analysts are divided over whether the debt ceiling fight will affect the tapering schedule, which the Fed is expected to announce in November.

"I would well imagine that the Fed would be highly averse to potentially adding to market volatility by announcing a taper if we are in crisis mode around the debt ceiling and debt downgrade issues," said James Knightley, chief international economist at ING.

If the debt ceiling fight drags on and the U.S. faces another credit rating downgrade, there could be a flight into government bonds but also some credit deterioration to Treasurys with rates already relatively low, said Padhraic Garvey, regional head of research for the Americas at ING.

Tapering in that environment "could cause the market to become unstable and rates to rise," Garvey said in an interview. "That's the risk."

But if inflation proves to be persistent, central bank officials may be compelled to press forward with tapering plans, even if a debt limit agreement appears doubtful into October.

"The Fed is going to look at any debt ceiling shenanigans as temporary even if they go on for six weeks," said Essaye.

Repo and reverse repo

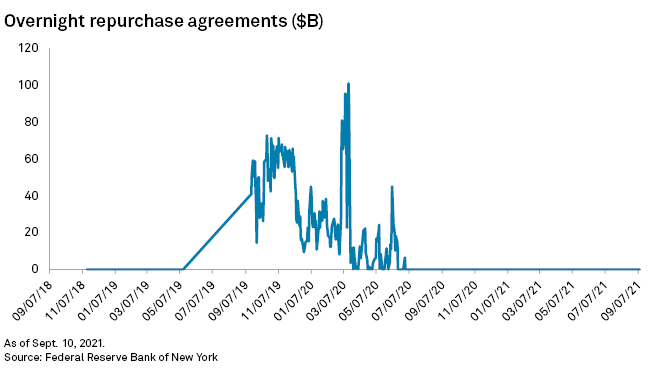

The looming debt ceiling deadline is also expected to have a significant impact on the repurchase agreement, or repo, market, in which borrowers can exchange low-risk assets such as Treasury securities for cash to meet certain obligations. The market also plays a critical role in the transmission of monetary policy, as the Fed's benchmark federal funds rate is influenced by movements in the repo rate.

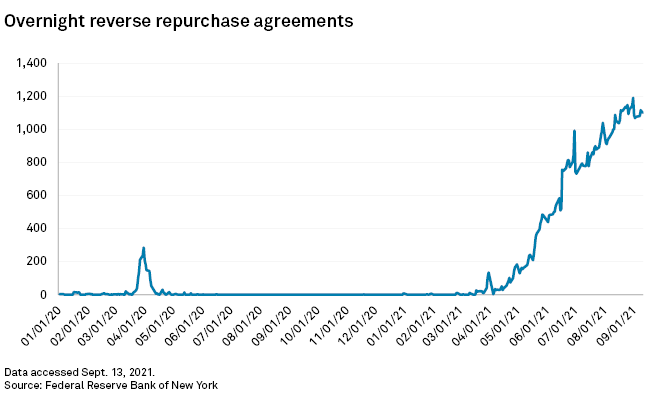

The Fed has facilities for repo and reverse repo operations, in which the central bank offers Treasurys for cash at a pre-announced offering rate. Thanks to low global rates and trillions of dollars in pandemic stimulus, demand for the Fed's reverse repo facility has soared this year as market participants seek to earn a low-risk return on their excess cash holdings.

Should debt ceiling negotiations drag on this fall, that demand is expected to increase further as the supply of Treasurys continues to shrink, said Barclays rates strategist Joseph Abate in a MarketWatch report. In the minutes of its July meeting, the Fed mentioned the possibility of raising its per-counterparty limit on reverse repo investments if "a number" of counterparties reach the limit and downward pressure emerges on overnight rates.

However, Tang with LH Meyer said debt ceiling turmoil could also result in heightened demand for the Fed's repo facility despite cash being in ample supply, especially if there is a chance that payments might get held up.

"All it takes is a bit of fear to make people want to hold cash instead of [Treasury bills], because even if the system looks safe, if I think that others might want to sell, I would want to sell before they do," Tang said in an email. "That would be a run or fire sale situation. It would be an extreme situation and quite unlikely though."

This S&P Global Market Intelligence news article may contain information about credit ratings issued by S&P Global Ratings. Descriptions in this news article were not prepared by S&P Global Ratings.