Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

5 Feb, 2021

By Brian Scheid

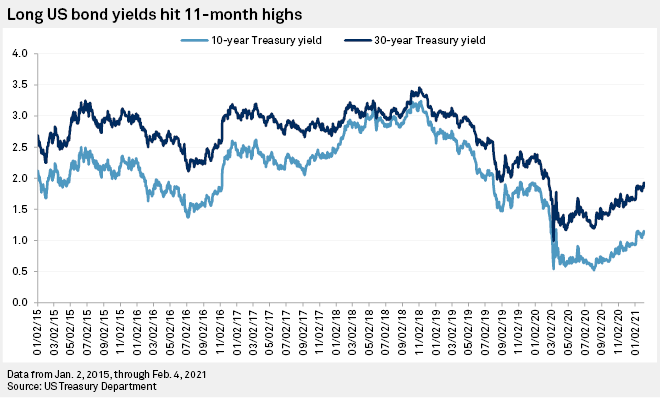

Long U.S. bond yields this week hit their highest points in roughly 11 months on trillion-dollar stimulus hopes, economic rebound prospects and inflation expectations.

The 10-year yield closed at 1.15% on Feb. 3 and Feb. 4, its highest point since March 2020. The 30-year yield closed at 1.93% on Feb. 4, its highest settlement since February 2020.

"Yields are up as the economy continues to improve," said Paul Schatz, president of Heritage Capital. "That should be the theme for at least the first half of 2021."

Schatz said he expects the 10-year yield to reach as high as 1.4% later this year.

The 10- and 30-year yields, which move inverse to prices, have jumped 19 and 23 basis points, respectively, since Democrats took control of the Senate, increasing the likelihood of another federal stimulus, potentially as much as $1.9 trillion.

"With economic data generally decent … the market is anticipating this injection of huge stimulus will push inflation higher, especially if vaccine distribution ramps up," said Tom Essaye, a trader and founder of The Sevens Report.

The improving outlook has pushed the yield curve to its steepest level since 2015. The gap between the 5- and 30-year yield reached 147 basis points Feb. 4, the largest spread since October 2015. The gap between the 2- and 10-year yield reached 104 basis points Feb. 4, the largest spread since May 2017.

Such steepening tends to signal rising inflation expectations.

"The bond market is anticipating that increased vaccine distribution globally will lead to a powerful global economic rebound later this year, and combined with all the stimulus, that should equal higher inflation," Essaye said.

The 10-year break-even rate, a measure of market inflation expectations, settled at 2.17% on Jan. 11, its highest level since October 2018.

Outside of inflation, however, the term premium, or the amount of compensation an investor needs to hold a long-maturity government bond, is a major factor driving yields up, said Michael Crook, deputy chief investment officer at Mill Creek Capital. Crook said that factor has been largely driven by Federal Reserve policy.

"The market believes the Fed is credible when it says rate hikes are a long way off, but is more focused on the Fed's tapering of asset purchases right now," Crook said.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has push back on talk of the Fed reducing its $120 billion in monthly bond purchases as early as this year, but investors do not appear entirely convinced, Crook said. The uncertainty has some preparing for an early tapering, which could cause Treasury yields to climb as much as 200 basis points from current levels.

"Even though Powell is pushing back on tapering discussion at this time, he's not doing a great job of clarifying which metrics the Fed will use to determine whether the economy has made enough progress to start tapering," Crook said. "Market participants respond to that uncertainty by requiring additional compensation (higher yields) for holding longer maturity Treasuries."

As long as the Fed keeps its bond buying program as-is, the purchases will continue holding down long-term yields even as they gradually rise with an improved economic outlook, said Patrick Leary, chief market strategist with Incapital, in a Feb. 4 note. The Fed's signaling that it would be patient on any short-term interest rate increases will also keep a lid on short rates, he added.

"This will keep short-term rates anchored and lead to further pressure on longer-dated bonds, assuming the Fed is able to achieve its goal of higher inflation expectations and realized inflation," Leary wrote. "So far, the data is going their way here."