Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

29 Sep, 2022

By Jon Rees and Cheska Lozano

British banks will benefit from rising interest rates even as some withdrew mortgages after volatile debt markets made pricing perilous for lenders, industry experts said.

The new government, led by Prime Minister Liz Truss, unveiled on Sept. 23 its plan to slash £45 billion in taxes and increase borrowing. The announcement, which came as annual inflation hovers around 10% and just one day after the Bank of England said the country was in a recession, roiled the pound and markets. The tax cuts also drew criticism from the International Monetary Fund, which said that it "did not recommend large and untargeted fiscal packages at this juncture" given the inflationary context.

Following the government's announcement, the pound plunged to a historic low against the U.S. dollar, leading the Bank of England to put out a statement saying it would not hesitate to raise rates to curb inflation if necessary. On Sept. 28 it resumed purchases of long-dated government bonds after warning of a "material risk to U.K. financial stability."

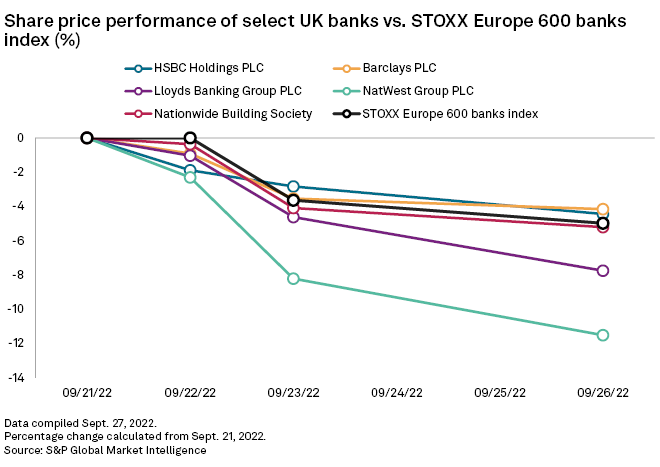

Though bank share prices have fallen since the government unveiled its plans, other encouraging economic indicators, such as low unemployment, mean the benefit of rising interest rates will still be a net positive for lenders, said Redburn analyst Fahed Kunwar.

"Higher rates are just better for banks' interest income on a fundamental level," Kunwar said.

Pricing pressure

Yields on U.K. five-year government bonds were higher than yields on those of Italy and Greece while yields on ten-year bonds, a government benchmark, reached a 12-year high of 4.25% before dropping back to 4.09% on Sept. 26. The yield on German government bonds was 2.11% on the same date.

Rising yields affect interest rate swaps, which mortgage providers use as a guide to mortgage pricing. The present volatility of the swap market has made lenders wary.

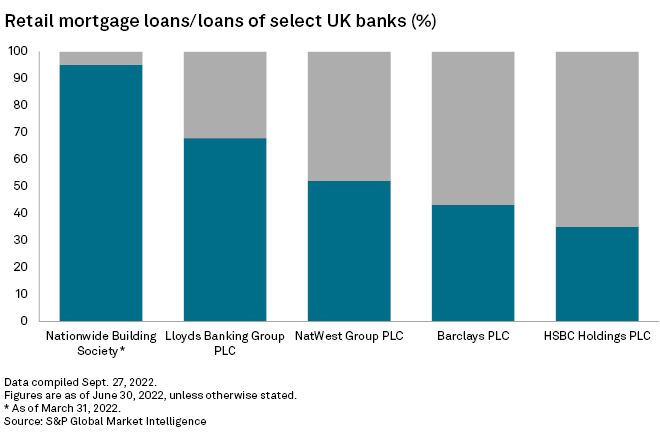

Nationwide Building Society, Lloyds Banking Group PLC and NatWest Group PLC have the highest proportion of mortgages within their loan books among the U.K.'s largest banks, S&P Global Market Intelligence data shows.

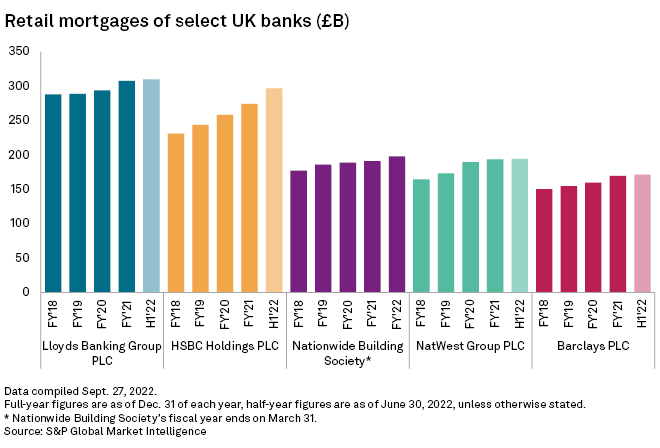

HSBC Holdings PLC, Santander UK PLC, Lloyds and Virgin Money UK PLC are among the groups that have paused offering new mortgage loans or withdrawn existing mortgages. Nationwide became the first big lender to increase its fixed rate deals with its two-year rate mortgage increasing to 5.59%. It offered a similar mortgage at 2.54% three months ago.

"Banks are withdrawing mortgage offers because their cost of funds has gone up so much," said Ray Boulger, senior mortgage technical manager at broker John Charcol. "Lenders have two choices: they can either immediately announce higher rates and take the risk that the markets will move again shortly and have to reprice, or else withdraw from the market until it settles down."

Bigger banks can afford to pause their offers and then reprice their mortgages in a volatile market, since new offers are likely to be a small part of their overall mortgage book, but smaller lenders have less flexibility, Boulger said.

The Bank of England, which raised interest rates to 2.25% in its Sept. 22 meeting, is next scheduled to meet Nov. 3 to assess monetary policy. Financial market analysts expect rates to rise by as much as 125 basis points to 3.5% in November.

Positive forecasts

All of the four major U.K. banks are forecast to grow net interest income year over year for full year 2023, according to Market Intelligence consensus analyst estimates. HSBC Holdings PLC, which, along with Barclays PLC, is more international in scope and has sharply increased its mortgage operations in the U.K. in recent years through its ring-fenced bank HSBC UK Bank PLC, is expected to record the biggest increase.

Profits are also forecast to rise at three of the four banks, with only Lloyds expected to post a slightly lower net profit on an annual basis.

While rising rates mean banks will also have to expect some increase in losses, these are unlikely to be significant as borrowers have built up more equity in their homes than in previous crises, Boulger said. Borrowers tend to prioritize mortgages above all other debts, and affordability tests introduced in the wake of the global financial crisis ought to make it less likely that they will get into difficulties with repayments, Boulger added.

"The issue is whether the rate cycle turns into a credit cycle and the key to that is unemployment," Kunwar said. "Historically, as long as unemployment remains low, and it is exceptionally low at the moment, then so have banks' loan losses."