| The global energy crisis "turbo-charged" installations of solar, wind and other renewable sources in 2022, the International Energy Agency reported in December. A record 2,400 GW of clean energy is expected to be installed from 2022 through 2027. Source: Marco Bottigelli/Getty Images News via Getty Images |

Several global developments in 2022 brought unexpected hope amid the deluge of alarming reports about ever-rising greenhouse gas emissions.

Although Russia's invasion of Ukraine forced some European nations to fire up coal plants and U.S. producers to ramp up drilling and exports of natural gas, the International Energy Agency reported in October that the large deployment of renewables globally offset the increase in pollution. As a result, global greenhouse gas emissions are now expected to increase less than 1% in 2022, defying expectations, the IEA said.

The energy crisis that forced some European nations to lower their climate ambitions will likely be a temporary setback, researchers believe.

There was also some fresh optimism after the COP27 climate summit, held in Egypt in November. Expectations for the conference had been low, but Brazil's newly elected president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva announced to euphoric summit participants that he would restore the Amazon rain forest and hold illegal loggers accountable.

In addition, U.S. President Joe Biden and China President Xi Jinping agreed to restart bilateral climate talks that had been suspended earlier in the year over trade disputes. And wealthy nations agreed to secure funding to compensate developing countries for loss and damage from climate change, a major breakthrough.

Then in December, the IEA brought more good news: The energy crisis had, in fact, "turbo-charged" installations of solar, wind and other renewable sources, especially in China and the European Union. China's electric car market is also growing faster than any other and is showing no signs of slowing down.

"The responses from governments to the crisis are going in the right direction," Fatih Birol, IEA's executive director, said in a Dec. 9 press release. "The unprecedented financial support we are seeing for clean energy transitions is improving energy security and dampening the impact of high fuel prices on customers."

The agency now estimates that renewables will make up more than 90% of global electricity capacity expansion between 2022 and 2027.

US within reach of 2030 climate goal

The U.S. also racked up some significant climate wins on the federal and state policy fronts this year even as the country's emissions were expected to inch up 1.5% in 2022, according to the Global Carbon Budget Report released in November.

The new policies will not on their own take the U.S. across its 2050 net-zero emissions goal line, but they will allow it to get closer to that line, researchers say.

The most important climate-related development in the U.S. was the passage of the bipartisan Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law in August. The legislation will channel nearly $370 billion in federal spending to decarbonization efforts over the next decade.

The largest investment in clean energy and climate reduction programs in U.S. history could cut economywide emissions by about 40% from 2005 levels by 2030, the Rhodium Group has estimated.

Power companies, some of which had balked at an earlier proposal for a national clean energy standard, applauded the tax credit provisions under the Inflation Reduction Act. The Edison Electric Institute, the trade group representing investor-owned utilities, called the law "transformational."

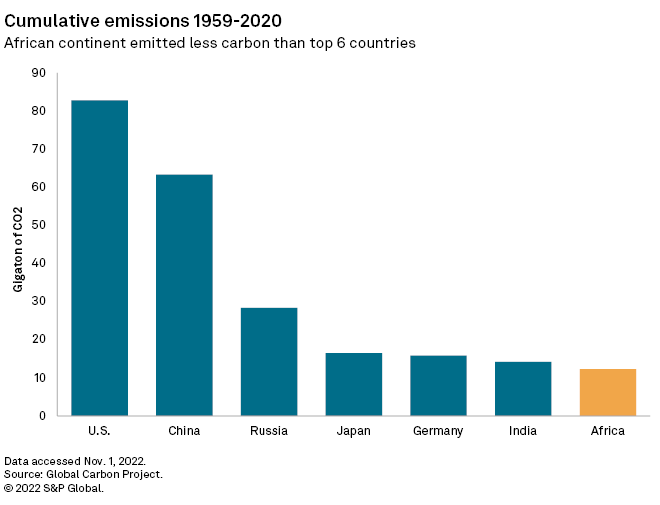

The legislation has been watched closely by other nations. The U.S. remains the second-largest greenhouse gas emitter after China and has historically released more carbon pollution than any other country.

"Thanks to the [Inflation Reduction Act], clean energy businesses will benefit from stable, long-term tax incentives like those enjoyed by the fossil fuel sector for more than a century," Gregory Wetstone, president and CEO of the American Council on Renewable Energy, told lawmakers during a Dec. 6 congressional hearing. "Congress has provided a welcome moment of hope in the face of a climate crisis."

Biden administration powered on

Still, researchers say the Inflation Reduction Act must be paired with other initiatives to fulfill the promise the U.S. made, under the Paris Agreement on climate change, to halve U.S. emissions by 2030.

To that end, the Biden administration in 2022 proposed tighter methane emission restrictions for oil and gas producers, building on a 2021 rule. The latest regulations are expected to avoid the equivalent of 810 million metric tons of carbon dioxide between 2023 and 2035 — almost as much carbon as all U.S. coal plants emitted in 2020, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated.

"Cutting methane pollution from the oil and gas industry is one of the most immediate and cost-effective ways to slow the rate of global warming while improving air quality and protecting public health," Jon Goldstein, a senior director of regulatory and legislative affairs at the Environmental Defense Fund, said in a statement.

Under a separate proposed rule, the administration is seeking to reduce methane pollution from natural gas and oil lease sites on federal and tribal lands. As a greenhouse gas, methane has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere.

States can 'go farther'

While governors and state legislators play a major role in implementing U.S. climate policies, many states are also moving forward with their own clean energy initiatives. Today, 24 states and territories representing 58% of the U.S. economy say they are on target to cut greenhouse gas emissions at least 25% from 2005 levels by 2025.

"What the states are doing is really critical," Casey Katims, the executive director of the U.S. Climate Alliance, said at a Dec. 2 congressional briefing. "We can also go farther than the federal government in many cases. We can innovate and push the envelope and create the next generation of climate actions."

Several of the states that are alliance members in 2022 set new or stricter climate targets than the Biden administration's nationwide 2050 goal for net-zero emissions. Maine's law calls for carbon neutrality by 2045, as does new legislation in Maryland, while Connecticut codified a 2040 zero-carbon target.

Other states established new interim targets or ramped up clean energy ambitions. California, for example, set a new goal to generate 25 GW of power from offshore wind by 2045. The state held its first offshore lease auction in December. California also announced a requirement in August to have all new vehicles be emissions-free by 2035.

Together, the Climate Alliance members obtain nearly half of their electricity from non-carbon sources, according to the coalition's 2022 annual report. That compares to about one-third for nonparticipating states.

Despite the advances, opponents of the president's climate agenda are gearing up for a court battle, empowered by the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark ruling in June in West Virginia v. EPA. The high court's conservative majority used that case to establish a new doctrine referred to as the "major questions doctrine," which states that courts should not defer to agency statutory interpretations that concern questions of “vast economic or political significance."

While the court did not detail how such determinations should be made, the new doctrine is being interpreted by some as sharply limiting the authority of federal agencies, including the power to issue new rules aimed at addressing climate change.

The Biden administration's emission standards for light-duty vehicles may be the first test of whether its regulatory climate initiatives will hold up to such legal challenges. In November, 16 Republican-led states asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit to halt "harsh new rules that unreasonably target car and light truck greenhouse gas emissions" they argued now fall outside EPA's authority.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.