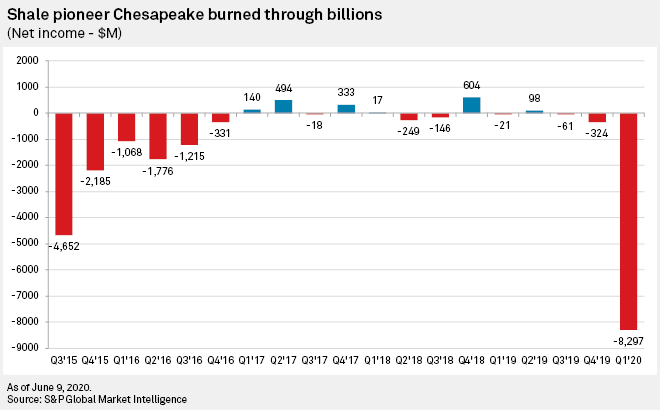

Years after failing to see its vision of a natural gas-powered future take flight, the driller that introduced "fracking" to the American vocabulary finally fell to earth. Chesapeake Energy Corp. filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection June 28, weighed down by billions in debt after two decades afloat on dreams and financial engineering.

Often accused, perhaps unfairly, of being a real estate company with a drilling rig parked in back, Chesapeake led the nation's "land grab" for shale oil and gas assets, investing indiscriminately in fields that would skyrocket and others that would flop. But, Chesapeake and others used fracking to produce far more gas than they could profitably sell; business plans devised around $6/MMBtu gas in the first decade of the century, collapsed at the $2/MMBtu pricing seen for the last few years.

At one time, Chesapeake was considered the model for independent oil and gas producers. But now in bankruptcy, the company has become a cautionary tale of what happens when growth is put ahead of budgetary concerns.

Fast out of the gates

Chesapeake was founded in Oklahoma City in 1989 by two men who would eventually become prominent players in America's shale revolution: Aubrey McClendon and Tom Ward. When shale gas production became more prevalent in the early 2000s, Chesapeake was at the forefront, snapping up positions in the Barnett, Marcellus and Haynesville Shales as rapidly as it could. As the company expanded, McClendon made it clear his vision for Chesapeake had few limits.

"We actually believe — not as a goal of the company so much, but just as a natural outcome of the growth plane that we're on, and also the decline path that some of our competitors are on — we'll likely be the largest gas producer in the country within two to two-and-one-half years," McClendon said in June 2007. The company went so far as to proclaim itself "America's Natural Gas Champion" and nearly made McClendon's boast come true. The company, at one time, became the nation's second-largest gas producer, trailing only Exxon Mobil Corp.

But as Chesapeake continued to expand its gas production and McClendon appeared at one industry conference after another touting the nation's natural gas future, something else was happening: gas prices were crashing. Ever the showman, Chesapeake's CEO started shifting the company's focus away from gas and toward shale oil. The results were as they were with shale gas: Chesapeake was at the forefront of the moment and seemed poised to capitalize.

As the company had with gas plays, Chesapeake began to invest in virtually every oil play it could. The debt began to pile up, but McClendon defended the approach by insisting the daring would succeed.

"For 150 years, this industry looked for oil and gas the same way it always did," he said in 2010. "But in five years … it was turned on its head. The winners of the next two decades to come will be the ones that acted with vision and conviction in these new plays. You either play or you don't play. And if you don't play … you're a loser forever."

McClendon justified his shopping spree in oil plays by claiming the rush to buy up assets would be fast and furious, ending by 2011. Unfortunately for McClendon and Chesapeake, a number of its bets turned out to be losers. The company aggressively went after shale oil plays in regions now largely considered second-tier at best or forgotten at worst. The list can be cringe-inducing to investors: the Mississippian Lime and SCOOP/STACK in Oklahoma, as well as the Cline and Eagle Ford shales in Texas, were major misses for Chesapeake. It invested heavily in the Utica Shale with the expectations it would be an oil giant, only to find it was another gas-heavy play.

The company's insatiable desire for growth, as well as its investments in the midstream sector, built Chesapeake into a company with a net value of $37 billion ― but also left it with considerable debt.

"It's the nature of the geology [of unconventional production]. You have to make very large front-end investments, and that kind of debt hangs over your forever," said Michelle Michot Foss, a fellow in Energy and Minerals at Rice University's Baker Institute. "The business model of the shale plays has always been tough."

Another problem faced by Chesapeake and other rapidly expanding producers was the reality that slowing down production was almost an impossibility. As it became a gas giant, Chesapeake had to drill to hold production and meet goals promised to shareholders. When it started to shift to oil production, the same costly process began again.

"It's the classic problem with economies of scale. On the gas side, it's been really hard to sustain the business. Over the years, oil has been the more valuable commodity. They followed the same strategy as everyone else and [got oil] back into the portfolio, and that [came] with a price," Foss said June 11.

Road to recovery becomes road to ruin

Chesapeake's net debt stood at more than $12.5 billion at the end of the fourth quarter of 2010, leading to the creation of the "25/25 plan" ― cutting debt by 25% over two years while increasing production by the same amount ― in January 2011. At that time, McClendon assured investors the company was done buying up assets and was entering a highly profitable "harvest mode." Chesapeake would maintain its best assets and exploit them while selling off others to help cut down debt. As part of this process, however, Chesapeake sold assets in the nation's most prolific gas play, the Marcellus Shale, to Southwestern Energy Co. Those assets have since become highly lucrative for Southwestern.

"This plan represents a fundamental shift from our aggressive asset accumulation of the past few years to a multiyear period of asset harvest, characterized by a clear focus on capital discipline and maximizing returns," he said. "Successful execution of our 25/25 plan should very substantially reward our shareholders in both the short and longer term."

It didn't work. Asset sales, largely in devalued gas plays, did not bring the desired returns. To add insult to injury, Chesapeake sold its holdings in the Permian Basin, now the crown jewel of unconventional oil production, in 2012.

Chesapeake's debt stood at approximately $10.28 billion and was rising at the end of 2011, while the always publicity-seeking McClendon was garnering headlines for all the wrong reasons. He was scorched when it became public that he had sold 31 million shares of company stock to cover margin calls between Oct. 8 and Oct. 10, 2008, as Chesapeake shares lost half its value. The board of directors later gave him a $75 million bonus, increasing his total compensation for 2008 to $112.5 million.

"When they made the margin call, they should have made some changes then," Morningstar analyst Mark Hanson said. "And giving McClendon a $75 million bonus? That's something you don't do."

Even with Chesapeake's debt issues piling up in 2011, McClendon ― who also served as the company's chairman of the board ― raked in $17.86 million in salary, bonuses and stock. That, along with the seemingly rudderless course taken by the company, began to infuriate investors.

"We're going into the Mississippian, then the Permian, then the Utica, then the Eagle Ford. Then you've only got one window in the Utica that's working, and the Williston was a bust. They've … tended to live and die by these big ideas that have imperiled shareholders. And they live and die by debt," Hanson said.

The last straw for McClendon came in April 2012, when it became public that he had taken out $1.1 billion in loans to cover his share of Chesapeake Energy's Founder Well Participation Program, which gave him a 2.5% stake in all Chesapeake oil and gas wells, provided that he paid 2.5% of the cost.

|

Shareholders, including activist investor Carl Icahn and major shareholder Southeastern Asset Management, forced the restructuring of Chesapeake's board and rejected the reelection of two of McClendon-supported board members at the June 2012 annual meeting. McClendon stepped down as chairman shortly thereafter and resigned as CEO under pressure in January 2013.

McClendon would not go quietly, starting another company, American Energy Partners, a short time later. His former company would later sue him, claiming he took proprietary information and used it at AEP; the suit was dropped after McClendon's death in March 2016 ― a day after he was indicted on federal bid-rigging charges.

The new CEO, Doug Lawler, came into the job with the mandate to cut debt and restore fiscal discipline at Chesapeake. Lawler saw success early on, helping drop Chesapeake's debt from $13.42 billion at the end of the first quarter of 2013 to $7 billion in the fourth quarter of 2014. But his task was made significantly harder by a two-year oil and gas price collapse from 2014 to 2016, and the debt began to creep up again.

"They wanted to build up positions and then flip them. They wanted to be in it for the long haul," Foss said. "The flipping part of this died in 2015. It's been very difficult to get out of these plays."

Even as rumors began to circulate that Chesapeake was considering bankruptcy earlier this year, Lawler struck an optimistic tone during the company's fourth-quarter 2019 earnings call in February.

"We have stripped massive costs from our system and reduced over $12 billion in debt and liabilities since we began our transformation, all while building and maintaining a standard of operational excellence and execution that is paramount for long-term value creation," he said.

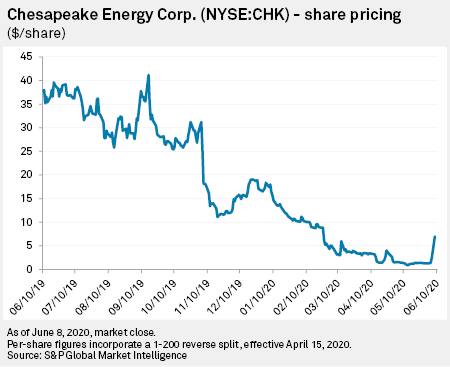

In spite of Lawler's confidence, Chesapeake's debt stood at $9.5 billion at the end of the first quarter and, with another price collapse and demand destruction caused by the coronavirus pandemic, there were few options left for the company, save for a bankruptcy filing. The once-mighty Chesapeake's market cap stood at just $114.7 million late in the day on June 28, and its stock was down to $11.85 per share.

It is likely Chesapeake will eventually emerge from Chapter 11, but in a form McClendon would not recognize. The company that was once in nearly every major unconventional play may once again be a gas producer in Appalachia.

"It was an exciting startup and in a particular business that happened to be more than everyone bargained for," Foss said. "Everyone [at Chesapeake] was proud of what they had built ... but they were a good example of the challenges."