The recent surge in the benchmark U.S. Treasury 10-year bond yield has bolstered the pandemic-battered U.S. dollar, but whether the greenback's momentum will continue depends on yields keeping a rapid pace of gains and if shorter-term bond yields begin to move.

"Yield is the driver now, but if short-term rates remain well-anchored ... then the upside for the U.S. dollar will be more limited," said Derek Halpenny, head of research for global markets EMEA and international securities at finance company MUFG, in an interview.

The U.S. Treasury yield curve is steepening, which is largely supportive of the dollar, Halpenny said, but short-term rates remain stagnant. That, Halpenny said, is "less supportive than an outright shift in the entire yield curve."

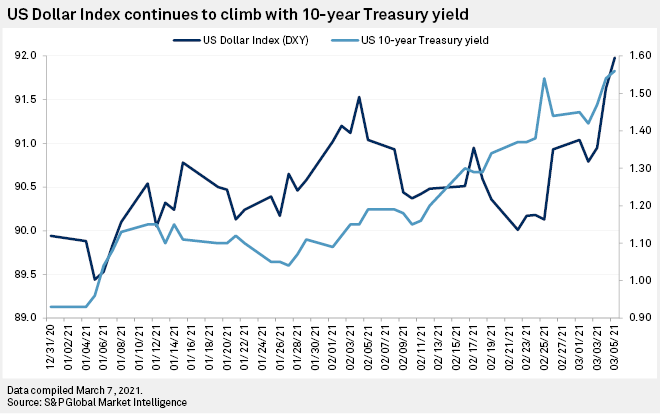

The 10-year yield surged to 1.54% on Feb. 25, up 61 basis points since the start of the year and the highest yield since Feb. 2020. The benchmark yield continued to climb into this week and closed at 1.59% on March 8, its highest settlement since Feb. 14, 2020.

The Dollar Index, which measures the U.S. currency against a basket of six peers, has risen with bonds, climbing 2% from 90.17 on Feb. 23 to 91.98 on March 5, its highest settlement since November. The index was trading near 92.40 on March 8.

Rising bond yields indicate a decline in demand for bonds and a rally in 10-year yield tends to indicate a positive outlook from investors on the U.S. economy.

While it may prove temporary, the jump in the 10-year yield has given life to the U.S. dollar, which struggled against its G10 peers throughout 2020.

Last year, all nine developed-market peers gained on the dollar, led by the Swedish krona, which gained over 12%.

This year, the dollar has reversed the trend, gaining on seven of nine of its G10 peers, lagging only the British pound sterling, which has gained nearly 1.1%, and the Canadian dollar, which has gained 0.4%. Since the rally in bond yields on Feb. 25, the U.S. dollar has gained ground on all nine of its G10 peers, including a more than 4.1% jump on the New Zealand dollar. The U.S. dollar has gained an average of more than 2.8% on its G10 peers since Feb. 25.

"Money tends to flow from countries with low-interest rates to countries with higher interest rates so that investors can earn the higher yield," said Marshall Gittler, head of investment research at brokerage BDSwiss Holding. "People borrow in low-interest-rate currencies and invest it in higher-interest-rate currencies. So when US bond yields move up, foreign investors buy dollars to buy those higher-yielding bonds and the dollar moves up."

Much of the current strength in the dollar is from how quickly the benchmark yield has risen, said Francesco Pesole, a foreign currency strategist with banking and financial services company ING, in an interview.

"The speed at which yields are rising is probably the key variable there," Pesole said. "A disorderly sell-off in bonds inevitably spills-over into market sentiment and hits the generally overvalued equity segment, all of which comes to the support of the safe-haven dollar."

Traditionally, however, it is the front-end of the bond yield curve — typically the yields on the government bonds that mature in two years or less — that influences the foreign exchange and this remains dollar negative, Pesole said. The carry trade strategy, which relies on borrowing in low-interest-rate currencies and investing it in higher-interest-rate currencies, is based on shorter rates.

While long-term yields have surged since Feb. 25, short-term yields remain grounded. The two-year yield, for example, settled at 0.14% on March 5, roughly where it has been since July.

Those short-term yields, and the ongoing steepening of the yield curve, are expected to continue, Pesole said, with the Federal Reserve firmly sticking to its accommodative monetary policies, including keeping rates near zero and continuing its bond-buying program.

"A volatile and disorder bond sell-off can continue to push the dollar higher," Pesole said. "A controlled rise in yields in line with vaccine-related recovery prospects and higher inflation expectations… does not automatically imply [U.S. dollar] strength."