Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

16 Feb, 2022

Cost of Care is a recurring column about the cost of U.S. healthcare, including drug pricing policy, regulatory decisions, investment in research and development, and more.

|

The disparity between the cost of drugs in the U.S. and abroad is pressuring legislators and experts to think creatively about the issue even as government-led efforts stall.

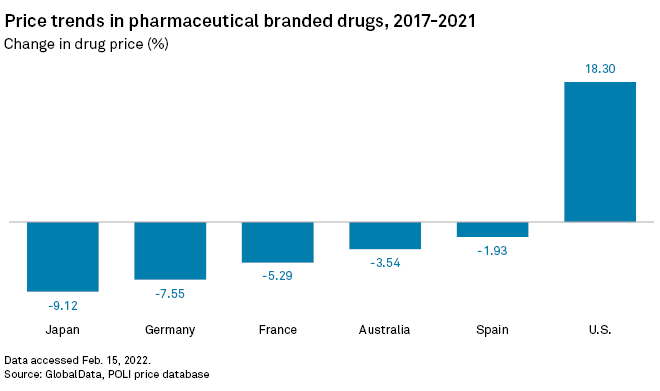

The price of branded pharmaceuticals in the U.S. rose by an average 18.3% between 2017 and 2021, while prices moved in the opposite direction in other developed countries such as Japan, Germany, France, Australia and Spain, according to a January report by data analytics firm GlobalData.

President Joe Biden's Build Back Better Act took aim at several of these dynamics, including proposals to allow U.S. insurance program Medicare to negotiate pricing and the creation of an international pricing index to maintain costs at a similar level to other countries. The bill was halted in Congress in December 2021, leaving lawmakers and health system experts to consider whether harnessing existing legislation or increasing transparency would have a similar impact.

"These leaders are taking a look at it and saying, 'OK, this can no longer be regulated by market forces, because it's getting too high and the population cannot pay for it,'" GlobalData Director of Healthcare Research and Analysis Floriane Reinaud said in an interview.

List prices in the U.S. were raised to compensate for mounting drug sale losses in other countries in the wake of the 2007 global financial crisis and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, Reinaud said.

Net drug prices in the U.S. — the actual cost to patients — can often be much lower than the list prices, thanks to insurance. Still, if the list price increases regularly, then the effect on the healthcare system is still detrimental, Reinaud said.

In the case of Biogen Inc. and Eisai Corp. Co. Ltd.'s recently approved Alzheimer's drug Aduhelm, the therapy had a list price of $56,000 upon launch, which was later cut in half as reimbursement faltered.

"Pharmaceutical companies have tried to, at least at launch, have a high price in the U.S. and then they try to increase that over time to compensate for the loss in other markets," Reinaud said. "Now it's getting the attention of the legislators in the U.S., so we see a lot more bad press."

The Bayh-Dole petition

One avenue legislators are exploring is the use of a decades-old federal law to allow competition to offset the high cost of an "unreasonably" priced drug. The Bayh-Dole Act, formerly known as the Patent and Trademark Act Amendments, enables universities and small businesses to own, patent and commercialize inventions developed under federally funded research programs.

Efforts to use the Bayh-Dole Act on pricing began in 2019 and were revived in a Feb. 8 letter from Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., and 11 fellow members of Congress, on the cost of prostate cancer treatment Xtandi from Japan's Astellas Pharma Inc. and partner Pfizer Inc. Xtandi was developed with grant funding from the U.S. Army and the National Institutes of Health.

The average wholesale price of the drug in the U.S. is $189,800 per year as of January, whereas in Japan the drug costs just $30,000 per year, they wrote in the letter to U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra.

"It is our strongly held view that it is not reasonable to charge U.S. residents as much as five times the cost for a drug invented using American taxpayer dollars than the price offered to residents of other high-income countries," the legislators wrote. They noted that Astellas has increased Xtandi's U.S. list price by 76% since entering the market in 2012, including a 5.9% increase in 2022.

The lawmakers requested an HHS hearing to weigh the decision to invoke "march-in rights," which would allow competitors to offer less expensive generic versions of Xtandi.

Astellas told S&P Global Market Intelligence that the company had invested more than $1.4 billion to develop Xtandi and the drug's pricing is in line with other prostate cancer therapies. Xtandi brought in ¥411.6 billion, or $3.56 billion, for Tokyo-based Astellas in the first nine months of fiscal year 2021, according to the company's earnings report.

What is reasonable?

Not everyone believes this is the correct use of the law, including Joe Allen, who was a professional staff member on the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee with former Senator Birch Bayh, D-Ind., and helped pass the act in 1980. Drug pricing has been challenged by similar petitions for 20 years, and they have all been dismissed, Allen said.

"If you're concerned about healthcare costs, which is legitimate, then address it head-on," Allen told Market Intelligence. "You can't misuse a tech transfer statute for doing things that it was not intended to do, because what's going to happen is you're not going to lower prices, you're going to kill innovation."

Without a clear definition of a reasonable price, the use of Bayh-Dole to fight high drug costs could lead to competitive misbehavior, Allen said.

The Bayh-Dole approach is similar to the argument to waive COVID-19 vaccine patents to accelerate access in lower-income countries, which also faced concerns about relinquishing intellectual property rights, said Allen, who is now president of Joseph Allen and Associates consulting firm.

"Certainly healthcare costs are a problem, and if a company's charging a price which is illegal, then they should be prosecuted," Allen said. "For that you have to pass a law, but what you can't do is misinterpret another law to get past that."

|

Muna Tuna, market access pricing and reimbursement leader at EY Business Consulting |

Transparency as a lever

The U.S. drug pricing system has too many obscured parts for either lawmakers or drugmakers to fix in one swift action, according to Muna Tuna, market access pricing and reimbursement leader at EY Business Consulting.

"There's really a lack of widespread understanding of the rationale behind drug prices, and given everything we're seeing with the current administration and past administrations as well, it's really not going to go away," Tuna told Market Intelligence. "For pharmaceutical manufacturers, they can either lead this topic or they can take a more reactive stance."

To take the lead, drugmakers should report how they decide on costs, which would convey the value of the medicines in relation to evidence, said Tuna, who advises life sciences companies.

"There are a few challenges to transparency, and some of it is just the way our ecosystem is organized with a level of confidentiality," Tuna said. "But there is also a lack of transparency because of the way that pricing of these drugs is articulated."

Knowing how value contributes to the determination of a drug's cost can lead to common knowledge to form a dialogue around pricing, Tuna said.

The relationship between manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers, who engage with payers and providers to determine the net price of drugs, is critical to articulating the value of drugs and reaching the right price, Tuna said.

"What's really important is getting pricing right from the very beginning of a drug's lifecycle, and what that entails is engaging with payers and PBMs earlier in the dialogue," Tuna said. "Whether the Build Back Better Act follows through or not, there will always be some uncertainty in our ecosystem around this topic, and getting the launch price right is the number one effort."