Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

30 Nov, 2021

By Brian Scheid and Michael O'Connor

|

Restaurant workers are quitting in droves, and rising wages have yet to entice them back. |

Low-wage workers are leaving their jobs in record numbers searching for better pay and working conditions, signaling a potentially historic transformation in labor bargaining power.

More than 4.4 million Americans, roughly 3% of the domestic labor force, quit their jobs in September, according to the latest U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The percentage of U.S. workers who leave their jobs voluntarily, known as the "quit rate," is now at its highest level since the bureau began tracking the metric more than 20 years ago and has increased steadily since May, as more than 20.2 million workers have since left their jobs.

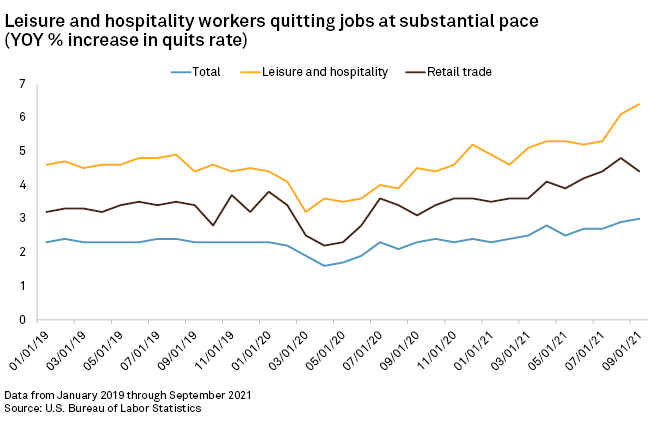

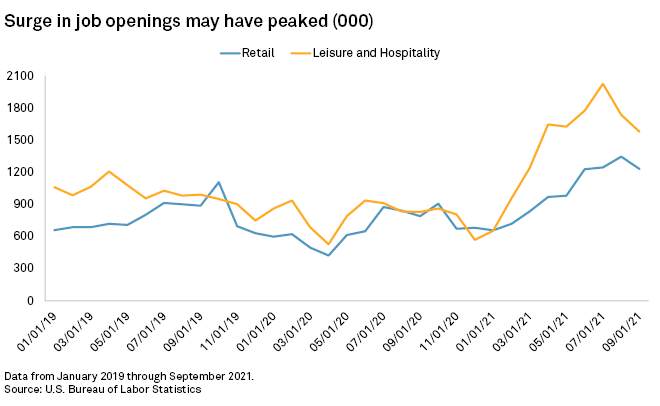

The starkest changes are taking place in sectors battered by the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in leisure and hospitality and retail jobs, where workers are quitting at record rates and employers are attempting to lure them back with higher pay and better working conditions.

The leisure and hospitality sector, a category of services jobs that includes fast-food cooks, waiters, hotel clerks and other relatively lower-wage positions, saw the number of workers who quit in September jump 6.4% in a year, the largest year-over-year increase of any employment sector. Quits in the retail sector jumped 4.4% from September 2020 to September 2021, above the overall average of 3%.

"This is a paradigm shift," said Aniket Shah, global head of environmental, social and governance and sustainability research at Jefferies Group. "The real, significant issue here is at the lower-income end of the spectrum. They're tired, they want more money and they want to be treated in a better way than they have been and they certainly were during COVID."

Intractable problem

Restaurants have struggled for years to balance tight margins with increasing labor challenges, but the pandemic supersized the restaurant industry's problems, according to David Henkes, a senior principal at restaurant research and consulting company Technomic.

"The nature of the restaurant industry, it's just not a particularly appealing thing for a lot of workers right now," Henkes said. "People coming out of the pandemic are looking for more out of their career and out of their jobs."

Squeezed by tight margins and rising costs, restaurant operators are limited in what they can do in response to the labor shortage, Henkes said. Rising wages have yet to offset workers' heightened health concerns, child care needs and desire for more stable work.

"It's in many ways an intractable problem," Henkes said. "If we talk in December of 2022, we will be having similar discussions about continued challenges that restaurants and food service operators are having."

Prior to the pandemic, EAT Restaurant Partners could rely on a stable pool of qualified workers for its 13 restaurants in and around Richmond, Va. Now, competition from other industries and the departure of so many from the labor market have made it harder to find experienced candidates, according to Chris Tsui, president of the company. EAT Restaurant Partners preferred hiring waiters with three years of experience but is now willing to take on candidates with less experience and put them through less training to get them working sooner, Tsui said in an interview.

"You've got to cut some corners because you just don't have enough people to work," Tsui said.

In an echo of what happened during the 2008 recession, many restaurant workers are leaving the industry with no intention to return given the improved mental health they gained in pursuit of other professions, according to Kiki Louya, a chef, former restaurant owner and executive director of the Restaurant Workers' Community Foundation. As the industry regains its footing, better working conditions, health benefits and career advancement opportunities can serve to attract workers, Louya said in an interview.

"On a day-to-day basis the amount of disrespect that you can get just in dealing with the public is really disheartening," Louya said. "It's less sometimes of a wage issue and more of just a people issue."

Labor competition

Intensified competition in the labor market and the broader trend of people rethinking the kind of working conditions they want are fueling the retail industry's struggle to fill positions, according to Mark Mathews, vice president of research at the National Retail Federation. A lower labor participation rate means industries across the economy are fighting for fewer workers, and the trend is impacting hiring in retail, which was already a high-turnover industry, Mathews said.

"Until we get to a situation where we get more people back in the labor force, we can expect to see continued competition to get people back working," Mathews said.

Rising wages in the retail sector could still attract more workers, Mathews said.

"Let's see where we stand in a few months once these wage rises have had a bit more of a chance to take effect," Mathews said.

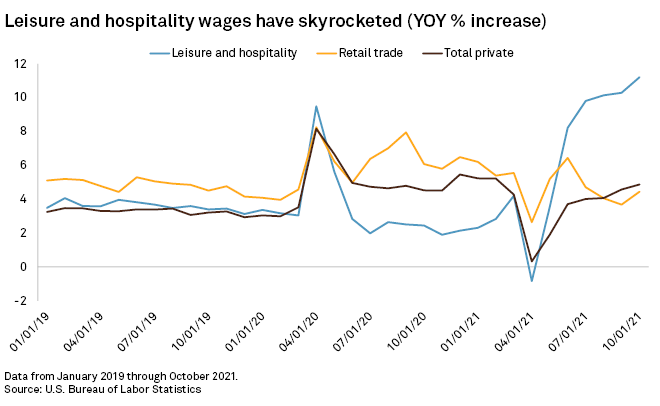

Attempting to retain workers and lure new ones, employers in the leisure and hospitality sector have boosted wages by more than 11% from October 2020 through October 2021, as all U.S. jobs saw a wage increase of about 4.9% over that period. The Bureau of Labor and Statistics will release November employment figures Dec. 3.

Great reshuffling

"These are signs of an economy in flux," said Claudia Sahm, a senior fellow at the Jain Family Institute.

Sahm, a former section chief at the Federal Reserve, said the jump in quit rates in restaurants and other relatively low-wage jobs is happening along with the shift from a services-oriented to a goods-oriented economy, as the pandemic caused consumers to spend more on appliances and automobiles and less on meals at restaurants and hotel stays.

This shift spurred a massive move of workers between sectors.

Waiters at downtown restaurants, now without their stable clientele of office workers, have found $15-per-hour warehouse jobs at Amazon.com Inc. Fast-food and grocery store cashiers, tired of health risks and unruly customers, have moved on to manufacturing and delivery jobs.

"It's more of a great reshuffling than it is a great resignation," said Daniel Zhao, a senior economist at Glassdoor. "It's not so much people throwing their hands up and giving up on work, it's more often people throwing their hands up and going to another job that offers better pay or treats them better."

A recent survey by Jefferies of employees aged 22 through 35 who quit their jobs within the past 18 months found that many respondents left for better pay at another job, but just as many resigned due to feelings of burnout.

The reasons for leaving also depend largely on education, which tends to correlate with pay. For example, respondents with only a high school education cited health concerns as a reason for quitting their jobs at a rate nearly four times that of respondents with associate or bachelor's degrees.

"We're not seeing huge amounts of turnover in high-end jobs, it's not people making a gazillion dollars [who] are going to reflect on aesthetics in the forest," said Shah with Jefferies. "This is really at the lower end of the spectrum of workers in terms of education and income."

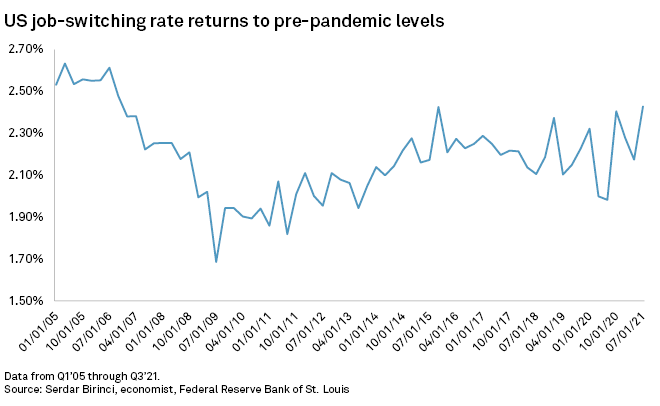

Workers are moving to new jobs at rates not seen since before the pandemic, according to an analysis of census data by Serdar Birinci, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The job switching rate, or the rate at which employed workers change jobs, climbed over 2.4% in the third quarter, up from about 2% in the third quarter of 2020 and the highest rate since the second quarter of 2008.

The rate differs based upon how much workers earn, Birinci said. Workers in the lowest earnings group, for example, switched jobs at a rate of 3.5% in the third quarter, while workers in the highest earnings group switched jobs at a rate of just 1.9%.

Worker leverage

The trend shows that the lowest-paid workers will likely emerge from the pandemic amid strong wage growth.

"Workers do have some leverage now," said Zhao with Glassdoor.

High quit rates and rising wages have led to signing bonuses and more flexible working conditions. It may also lead to an increase in bargaining power. Workers at Deere & Co. in November ended a five-week strike with a deal that included an immediate 10% raise and an $8,500 signing bonus.

Still, Sahm said those gains in bargaining power may be uneven.

The pay increase for Deere workers came amid a surge in demand for tractors. Custodial workers at downtown office buildings, largely vacated by companies that shifted to work-from-home, will likely have less power to negotiate for a higher salary.

"The workers have to be where the demand is," Sahm said.

The era of American companies with access to a readily available, easily replaced army of low-wage workers may be over, said Shah with Jefferies.

"The worker is becoming much more aware of their working conditions and is asking fundamental questions of whether they want to work in that environment or not," Shah said. "Employment shocks like this can really change the outlook of employees."