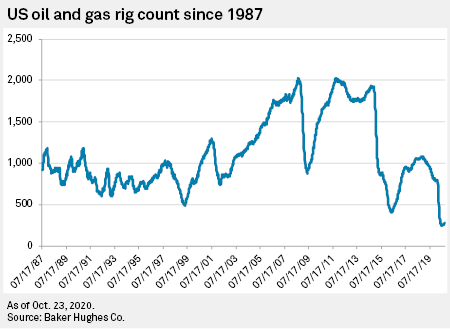

The U.S. oil and gas industry is flat on its back, with the fewest rigs in the field since consistent records were kept.

The shale boom — an all-American oil and gas frenzy fueled with cheap money funding pricey horizontal drilling rigs that produced record supply — is now a bust, cut off at the knees as the world retreats into its living room to wait out the coronavirus pandemic.

The oil and gas industry is no stranger to boom-and-bust cycles. However, the speed and severity of the latest downturn, coupled with the uncertainty of a global pandemic on an industry that is on the verge of an energy transition, has even the most optimistic industry veterans wondering if oil and gas will ever see another boom.

"What came out of the blue in the last seven months is COVID[-19], which is the worst disruption to global oil demand in modern history," Raymond James & Associates oil, gas and clean technology analyst Pavel Molchanov said. "That was the catalyst of the oil crash."

Anthony Lucas's gusher, the first in Texas, blew on Jan. 10, 1901, on Spindletop hill in Beaumont, Texas, and sprayed over 100 feet above the derrick for nine days until the well was capped. Source: Texas Energy Museum/Newsmakers via Getty Images |

A history of cyclicality

Mergers and acquisitions in the oil patch is one of the classic responses. John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil bought up refineries, pipelines and producers in the early 20th century, trying to bring order to a chaotic industry through monopoly. The courts eventually broke up Standard Oil — at one point estimated to control 90% of the country's oil and gas business — because of anti-trust issues.

Standard Oil's direct descendants still produce, ship and sell oil and gas under names like Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp. and ConocoPhillips, with other parts of Standard Oil doing business as units of BP PLC, Marathon Oil Corp., Marathon Petroleum Corp. and Sunoco LP, among others.

Boom and bust has been with the oil industry since its birth in Pennsylvania's Appalachia. Three years after Edwin Drake drilled the first oil well in Titusville in 1859, more and more "rock oil" chased prices that got as high as $10 per barrel in January 1861, only to crash to 10 cents per barrel by year's end.

Like Pennsylvania in the 19th century, the U.S. oil and gas industry and its hundreds of exploration and production companies is splintered and ripe for consolidation when prices are low, Molchanov said.

"What this acceleration in M&A tells us is the smaller players see strength in numbers, strength in scale, and the smaller players are willing to sell the business … at valuations that in the past would have been perceived as too low," Molchanov said.

"We expect consolidated markets with higher barriers to entry to show clear profitability improvements: as capital becomes scarcer, the industry typically gets better at managing existing infrastructure and returns improve," analysts at Goldman Sachs said in an Oct. 22 note. "Shale's fragmented ownership at the moment prevents effective logistics and data management, making it the marginal producer and increasing pressure for it to consolidate further."

Can low prices be the cure?

The crippling of demand caused by COVID-19 accelerated what were existing structural issues of overproduction and low prices, observers said, all occurring in the shadow of hydrocarbon demand shrinking as the developed world sets zero carbon emissions and decarbonization goals to flight climate change.

Will the classic adage, "low prices cure low prices," bring buyers and consumers back to oil and gas, igniting the next boom?

"I have talked to some people that think there is going to be another boom," Regina Mayor, global head of energy for KPMG, said. "They're convinced that they can see it two-fold: that there will be a $5 [/Mcf] gas and that, with the lack of development in 2020 and 2021, then there will be a rebound to triple-digit oil prices."

"I am not bullish we will see this scenario," Mayor said. "I think it is bad because it's not going to be a return, a renaissance in fossil fuels. We're going to have to figure out our role in the energy transition and our place in a less fossil fuel-centered world."

Oil and gas acquisitions and divestitures attorney Austin Lee, a partner in Bracewell LLP, began his career as an oil and gas landman signing owners up for production leases before he went to law school. He is an oil optimist. "I don't think anybody is going to admit to there being a last boom in the oil industry," Lee said. "That's kind of part and parcel of the way things work in the business."

"What you're seeing right now in the way of M&A, in the way of restricted access to capital, to layoffs … is that the industry is being forced to react to forces like supply and demand, which had an unprecedented black swan event in the last six months," Lee said.

Charles Beckham, an attorney with Haynes & Boone LLP, a firm specializing in oil and gas bankruptcies, agrees. "I don't think we're going to end up with a bunch of giants [large independents through consolidation] and that's it," Beckham said. "The entrepreneurial spirit of the independent oil and gas producer still survives. They've taken some punches in the nose, but those people believe. You don't drill a well if you don't believe."

'If there's money to be made, money will flow'

|

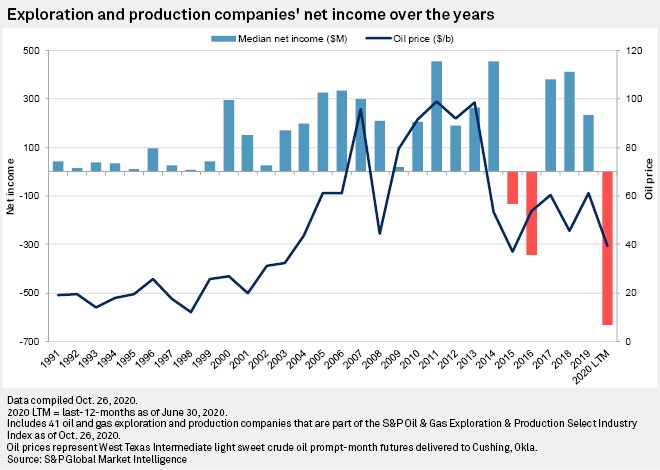

Booms and busts are endemic to the oil and gas industry because forecasts and the commodity price set by supply and demand do not always agree.

"New wells get drilled when demand is high, but they don't stop pumping when demand goes down," Richard Newell, the president and CEO of Resources for the Future, an established energy and environmental think tank, explained.

"That's the short-term dynamic, which I think is largely unchanged, except that shale oil has made the system more responsive more quickly," said Newell, who was the administrator of the Energy Information Administration, the federal government's energy data arm, from 2009 to 2011. "In the background of this short-term dynamic is the long-term trend. And that's where the bigger change is happening."

Newell said three areas of uncertainty that make forecasting difficult: the rate of economic growth and thus demand for energy, in a pandemic environment; the pace of technological innovation in energy efficiency and renewable power; and the wild card of government policy changes in reaction to climate change. "The third very important one is the speed and stringency of clean energy and climate policy and I think that, that's the biggest single factor," Newell said.

"Current policy is heading us in the direction of roughly flat oil demand globally at around 100 million barrels per day after a short-term recovery from COVID," Newell said, as demand from growing economies like China and India offsets declining demand from developed economies in Europe and the U.S. "Business as usual, that itself is a change. You see that in BP's outlook, you see that in OPEC's outlook, you see that in the International Energy Agency's outlook"

"But if there's money to be made, money will flow," Newell said. "I wouldn't totally overdo it and we have — there's a lot of private equity now."

New capital might be hesitating at the thought of financing another boom. "What I'm hearing from investors is that limited partners don't want to be in oil and gas," said Andrew Gillick, energy data firm Enverus' managing director and energy sector strategist. He said private equity investors are "following the money and the money is going into renewables."

"The question is, how are you handling the energy transition?" KPMG's Mayor said. "Are you the Netflix that survives or the Blockbuster that goes out of business?"