Rising interest rates in Japan could drive up credit costs for banks and crimp lending if the central bank accelerates its policy normalization.

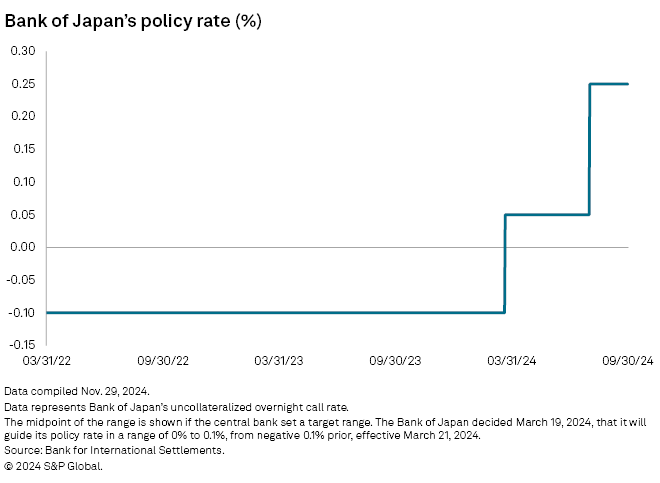

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) is expected to announce another rate increase as early as this month as the central bank moves further away from its experiment with negative rates, which it abandoned in March with the first hike in nearly 17 years. A second rate hike in July took the benchmark interest rate to 0.25%. Economists expect the rate to rise to 1.0% by 2026, based on inflation and economic growth numbers — and this at a time when the rest of the world looks at monetary policy easing.

While higher rates can help boost net interest margins at banks, they can also dent loan demand by driving up the costs for borrowers.

"The biggest challenge banks could face [from higher rates] would be credit cost," said Hideo Oshima, senior economist at Japan Research Institute, a unit of Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group Inc., one of the nation's three megabanks. "Higher rates would pose the risk of cash-strapped companies falling into a worse funding environment," Oshima said.

Balancing act

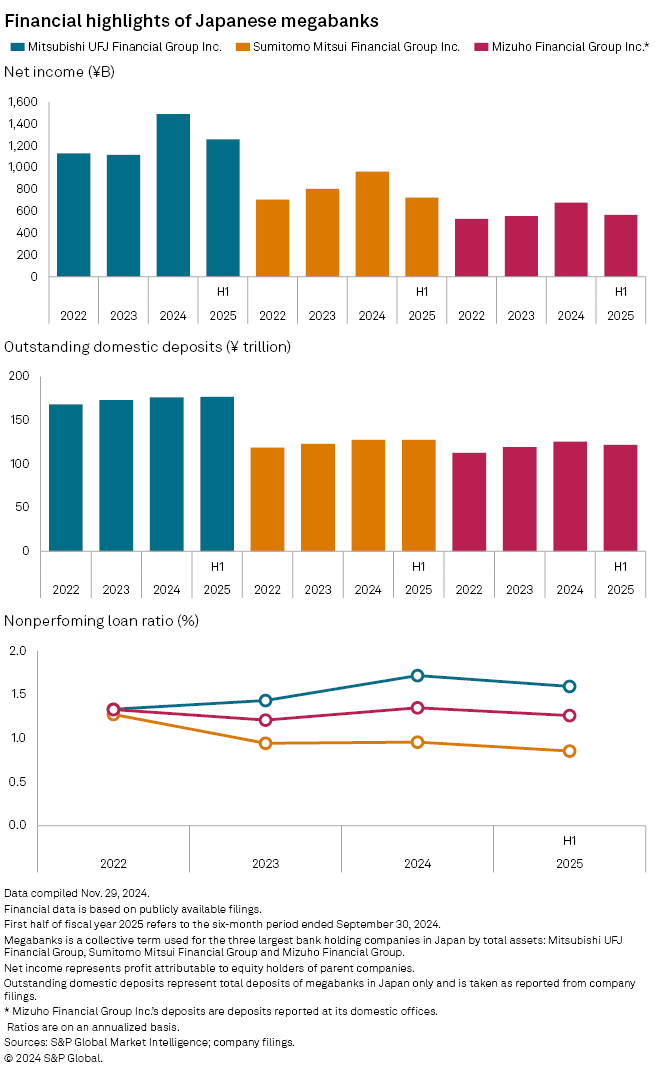

The BOJ, under Governor Kazuo Ueda, faces a delicate balancing act as major global central banks, especially the US Federal Reserve, are poised to cut rates to stimulate economic growth. Several Japanese banks have business operations outside Japan, which means both domestic and international policy moves will have an impact. Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc., Mizuho Financial Group Inc. and SMFG, the three megabanks, have substantial lending in the US and are among the world's biggest holders of US Treasurys, making them directly and indirectly exposed to global rate cycles.

"While it is unlikely that the credit cost ratio [at banks] overall will increase substantially, with the price pass-through gradually spreading, future developments warrant careful attention," the BOJ said in its Financial System Report in October.

Deposits under pressure

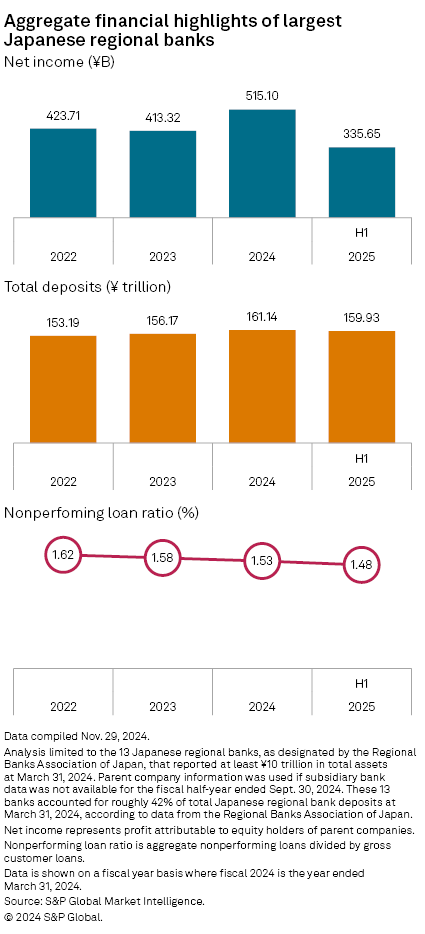

Deposits at banks could also come under pressure from higher rates.

"Money shifts to higher-yielding place[s] or products," SMFG CEO Toru Nakashima said during a Nov. 14 earnings press conference. "That’s why our domestic deposits declined."

Rising rates could cast a shadow over the economy, which would be a headwind for banks, said Takahide Kiuchi, executive economist at the Nomura Research Institute. Japan's economy grew 0.3% for the July-to-September period from the previous quarter, on a seasonally adjusted basis. The country's year-over-year inflation rate was 2.3% in October, slightly above the BOJ's 2.0% target.

Megabanks often have a better ability to pass higher rates to their borrowers as more of their customers are financially stronger. Still, higher rates trigger backlash from customers and intense competition for deposits. Aggregate lending growth at Japanese banks slowed to 3.0% year over year in October, from 3.5% in July, according to BOJ data. Major banks, which include the three megabanks, posted an even sharper drop in lending growth — to 2.5% in October, from 4.1% in July.

"Although higher interest rates are more often positive for banks in general than lower interest rates, naturally it depends on the competitive dynamics for both lending and procuring deposit funding," said Michael Makdad, a senior analyst at Morningstar. "We cannot say that higher interest rates are always positive for banks' net interest margins."

Rising stress

Bankruptcies are already on the rise in Japan. A total of 8,323 small businesses filed for bankruptcy in the first 10 months of this year, up 17.6% from the same period of the previous year, according to data from Tokyo Shoko Research. The final tally for the year may cross 10,000 in 2024 for the first time in 11 years, Tokyo Shoko estimates.

Stress may not be limited only to smaller companies.

"I doubt increasing bankruptcies will remain limited to smaller companies," said Toyoki Sameshima, a senior analyst at SBI Securities. A potential extension of default risks to larger companies would tarnish assets even at larger local lenders and major banks, Sameshima said.

Regional banks, which have a greater proportion of small businesses as customers, have less leeway to pass higher rates to their price-sensitive borrowers. Deposit rates offered by all banks rise in tandem across all lenders due to competitive pressures.

Regional lenders cannot "raise lending rates forcefully because they have been supporting local businesses in a rural community," Japan Research Institute's Oshima said. AAs a result, more than half the Japanese local lenders failed to improve net interest margins for the fiscal first half to September from the same period of the previous year. Oshima noted that these lenders delayed raising lending rates for many customers.