Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

15 Nov, 2022

| Ford Motor Co. and SK On broke ground on a new electric vehicle and battery complex in Tennessee in September. Observers say electric-vehicle makers will need to do more than sign off-take deals with miners if the world aims to achieve net-zero by 2050. Source: Ford Motor Co. |

It is time for electric-vehicle makers to go beyond lithium off-take agreements and get more involved in mining and processing, industry observers said.

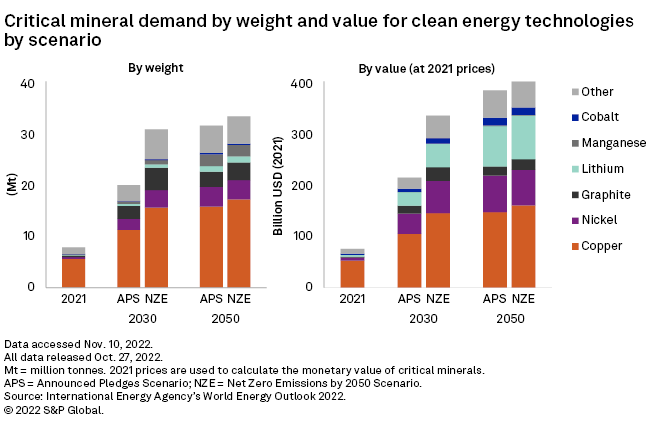

Recent price increases for certain metals showed their vulnerability to supply chain disruptions, which threaten to boost the cost of clean energy technologies and slow their deployment, the International Energy Agency, or IEA, said in its World Energy Outlook 2022, published Oct. 27.

"With rapid demand growth, [electric vehicle] makers are likely to strengthen their efforts to secure stable supplies through various ways, including not just long-term off-take agreements, but also equity investments, joint ventures and direct investments in mines and processing facilities," IEA Energy Analyst Tae-Yoon Kim told S&P Global Commodity Insights.

The challenge is particularly acute for lithium. Lithium prices have risen to even greater record highs, proving resilient against economic pessimism and China's COVID-19 lockdowns that have tempered other battery metals' prices. While the IEA sees significantly less lithium will be needed for the world to be carbon neutral by 2050 than thought just a year ago, it also suggested EV-makers may need to invest in miners neglected by some jurisdictions that have prioritized battery cell production over building out raw material supply.

"It's the car companies that need the lithium, but it's the car companies that are not writing the checks for that to happen," Canaccord Genuity head of mining research Reg Spencer told Commodity Insights, referring to the investments needed to get mines up and running.

"I see a not-too-distant future where you will start to see upward integration by the original equipment manufacturers [or OEMs]. You've seen them already start to move up into the midstream by planning to make their own batteries as Tesla Inc. does, but to make not only cathode materials but the metals feedstocks."

New mines needed quickly

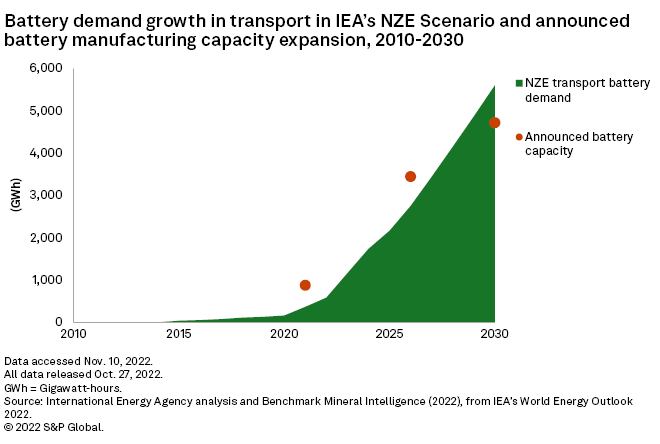

Battery cell-makers are "well-placed" to respond to increasing annual battery demand through 2030 thanks to strategic early investments in battery plant capacity, according to the IEA's net-zero emissions model. But the Paris-based agency warned that the supply of battery metals will need to rise well before new plant capacity could come online.

"While battery production factories can be built in under two years, raw material extraction requires investment long before production reaches scale. Investments in new mines will need to increase quickly and significantly if supply is to keep up with the rapid pace of demand growth," the IEA warned.

Though there are 320 battery facilities currently in various stages of production, the industry "neglected to finance and develop future raw material supply" when it was building battery production capacity, Argentina-focused lithium developer Lake Resources NL Executive Chairman Stuart Crow said in an interview.

"That is the reason we now have a supply deficit," which will remain for at least the next five to 10 years and continue to drive up prices, Crow said.

The lack of large-scale investments and large corporates entering the still-nascent lithium sector has been the main challenge in the last decade, Anand Sheth, founding chairman of the recently-formed International Lithium Association, told Commodity Insights in an email interview.

|

| International Lithium Association founding chairman Anand Sheth. Source: Paydirt media |

However, "we now see larger corporates and OEMs supporting the resource sector," Sheth said, and more of this needs to occur, "not only by OEMs, but potentially other companies too that believe in this transition."

Major disconnect

About $45 billion will be needed to meet lithium demand by 2030 alone as the industry's capital intensity has risen about 50% in the past four years, according to Spencer.

And carmakers have done little to help miners out, Spencer said. "At last count, ex-China OEMs had committed over $500 billion towards electrification, yet not one of them has committed any investment towards extraction of battery raw materials."

Owning lithium mines is a way EV-makers can mitigate their exposure to high lithium prices by ensuring security of supply, Spencer said. It also makes their batteries cheaper to produce, as they would effectively be paying about $10,000 per tonne for the cost of lithium production rather than $70,000/t for lithium chemicals to put into their batteries.

Spencer pointed out a "major disconnect" between what the customers want to do and where they think the material will come from. "If no one invests in new supply and demand stays high, there will be very high competition for a limited material which is going to be hideously expensive," Spencer said.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.