Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

24 Sep, 2021

|

Democrats' fuel-neutral approach to hydrogen deployment is putting the party's energy policy leaders at odds with climate activists and environmental justice advocates, who want a hydrogen production process that uses clean energy. Source: Getty Images North America |

After U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm met with grassroots organizers in Brooklyn in June, the leader of Latino community organization UPROSE was optimistic about the Biden administration's outreach to citizens on climate policy. However, the community leader expressed concerns over one of the administration's energy policy priorities: harnessing the potential of hydrogen coupled with carbon capture and sequestration.

Hydrogen derived from fossil fuels and the supporting technology are "false solutions" in the view of UPROSE Executive Director Elizabeth Yeampierre. The efforts would benefit big corporations at the expense of communities of color like hers in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. "They haven't even been able to show that these interventions work," Yeampierre said in an interview after the meeting. "But what we do know for certain is that they don't produce the benefit that is necessary for climate change, and they harm our communities."

Yeampierre's comments reflected a rift that has emerged between climate activists and the Democratic-controlled White House and Congress over how to use hydrogen to decarbonize the economy. While the administration plans to fund multiple pathways for hydrogen production, including using natural gas and nuclear power, many environmental groups adamantly oppose using anything besides zero-carbon renewable electricity.

The split threatens to complicate the Biden administration's pledge to fight climate change even as it gives environmental justice groups a bigger role in policymaking. Under a federal government definition, environmental justice communities are low-income or minority populations that have historically been vulnerable to industrial development.

Congressional Democrats have signaled that they will take a technology-neutral approach to low-carbon hydrogen deployment. The U.S. Department of Energy has also embraced various forms of hydrogen — in an effort it calls Hydrogen Shot — from the product of renewable-powered electrolysis known as green hydrogen to the product of natural gas reforming with carbon capture known as blue hydrogen.

"We're really trying to get away from the color," Sunita Satyapal, director of the DOE's Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office, said in an interview. "It's difficult to have a one-size-fits-all. The point is really the clean hydrogen and the carbon intensity."

But climate groups have built support around a single pathway: green hydrogen produced using zero-carbon renewable electric power. These groups argue that the nation should only produce green hydrogen for a handful of hard-to-decarbonize sectors, including industries that currently rely on carbon-intensive hydrogen, such as petroleum refining, metals treatment and fertilizer production, aviation, long-haul road and sea transport, and high-heat industrial processes like steelmaking.

"By ignoring the impacts to climate change, public health and the environment, proponents of blue hydrogen are essentially pushing for more fossil fuel development, including fracking, pipelines and harms to Black, Indigenous and other people of color, often hurt first and worst because of the systemic patterns of industrial development built alongside marginalized communities," said a group of roughly 150 national, state and local organizations in a Sept. 7 letter to Democratic leaders.

Political rifts like this are not new, but environmental justice groups have historically lacked a national platform to amplify their positions, according to David Konisky, an Indiana University professor who has studied the groups' relationship with the federal government.

"What is a little bit different today is that the Biden administration has made considerable efforts to have the environmental justice community represented throughout government," Konisky said in an interview. "And these organizations, these individuals feel empowered to voice their opposition and to expect the Biden administration to not just listen, but to change policy accordingly."

Blue hydrogen becomes wedge issue

A scientific paper finding that the combustion of blue hydrogen for heat is worse for the climate than burning natural gas has helped environmentalists press their case to policymakers. But the paper has attracted scrutiny from some researchers, and the Senate's bipartisan infrastructure bill includes substantial support for blue hydrogen and other production pathways opposed by environmentalists.

"This is an all-of-the-above fuel," Sen. Joe Manchin, D.-W.V., said at the DOE Hydrogen Shot Summit 2021, which ran Aug. 31 and Sept. 1.

A recent DOE request for information showed substantial interest among U.S. stakeholders in developing blue hydrogen. The DOE Loan Programs Office is considering about $3 billion of loan guarantees to hydrogen projects, Jigar Shah, the office's director, said at the summit.

Through Hydrogen Shot, the DOE will aim to cut the cost of clean hydrogen by 80% to $1 per kilogram within a decade, a goal that could be easier to reach with blue hydrogen if U.S. gas costs stay low and carbon capture technology improves. On the other hand, hydrogen from renewable energy today averages $5/kg, according to the DOE. Some policymakers believe blue hydrogen will be critical to scaling up demand while green hydrogen costs fall.

Defining 'clean hydrogen'

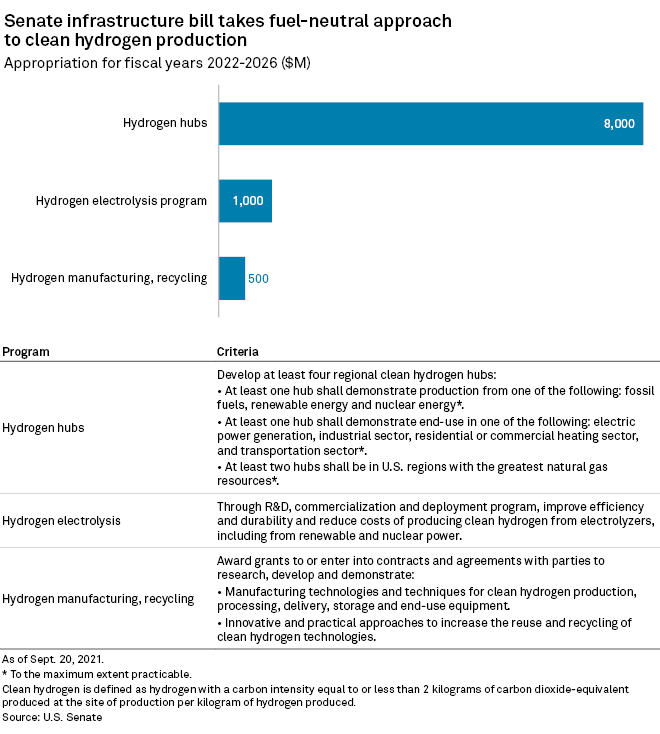

The infrastructure bill would refocus a long-running DOE hydrogen program on producing strictly "clean hydrogen." The bill initially defines clean hydrogen as yielding no more than 2 kilograms of carbon dioxide-equivalent greenhouse gas emissions for each kilogram of hydrogen at the production site.

The DOE has not yet provided a definition for clean hydrogen. The agency has begun to develop an agreement on such a definition and other standards through the International Partnership for Hydrogen and Fuel Cells in the Economy, or IPHE, comprised of 21 nations and the European Commission. International standards will be critical to a global low-carbon hydrogen trade that actually delivers climate benefits, according to energy experts.

|

The U.S. has the resources to produce both green and blue hydrogen at scale, so it has the potential to become an export leader, Bernd Heid, a senior partner at McKinsey & Co. Inc. who leads the consultancy's global hydrogen service line business, said at the summit.

"Globally, there's a lot of interest in increasing [hydrogen supply], because we know that some countries will not be able to meet their climate goals just with the clean electrons," said the DOE's Satyapal, who serves as co-vice chair for IPHE.

Competing views within environmental justice communities

Hydrogen's potential to spur economic development is particularly exciting where the opportunity exists to repurpose fossil fuel infrastructure in economically distressed areas, said Kate Gordon, senior adviser to Granholm, on an environmental justice panel at the summit.

Yet in a sign of the impasse over blue hydrogen, Anthony Rogers-Wright, director of environmental justice for New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, or NYLPI, pushed back on Gordon's assessment in his opening statement.

"It's important to be clear from the outset that while environmental justice communities and organizations accountable to them — allies like NYLPI — have no aversion to innovation, we do consider the proliferation of fossil fuel infrastructure, use and disposal — especially in environmental justice communities — anathema to climate and environmental justice," he said.

|

U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm discussed place-based approaches to implementing federal climate policy with UPROSE Executive Director Elizabeth Yeampierre in Brooklyn, N.Y., as part of the Biden administration's efforts to engage frontline communities. Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence |

NYLPI is worried that hydrogen deployment will produce exactly that outcome, Rogers-Wright added. New York environmental justice communities are also concerned that efforts to blend hydrogen in power plants and distribution systems will crowd out community solar projects and building electrification, said Sonal Jessel, director of policy at WE ACT for Environmental Justice.

But representatives of Native American communities called for the DOE to support hydrogen development pathways.

The Crow Nation in southern Montana has long sought to develop its large coal reserves and gas resources, and it now sees potential in carbon capture-enabled hydrogen production, said CJ Stewart, energy director for the tribe's executive branch, at the summit.

The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of southeastern Idaho have an interest in leveraging their relationship with the DOE's Idaho National Laboratory and their agricultural economy to develop hydrogen from nuclear and biomass, Tribal Energy Department Director Talia Martin said.

"Membership and leadership work to determine what's the best thing for the tribes by looking for technologies that will provide the community with environmentally and economically friendly energy technology," Martin said. "This is really important where the poverty rate is higher than the national average."

The exchanges at the summit illustrated the DOE's challenge in taking a place-based approach to developing hydrogen hubs. The DOE has aimed to prioritize a range of communities, including those facing energy cost and access burdens, environmental justice communities and fossil fuel-dependent economies at risk of being left behind in the energy transition, Gordon said.

The hydrogen policy also committed the DOE to "deep engagement" with communities to develop strategies through shared decision-making, Gordon added. "That is a big shift for a lot of us at DOE, I will be honest."