With commodity trade finance suffering from low volumes and high loan losses during the coronavirus pandemic, banks are retreating from the market. That leaves a funding vacuum that will be painful for midsize companies in particular, but which may attract alternative lenders, according to industry observers.

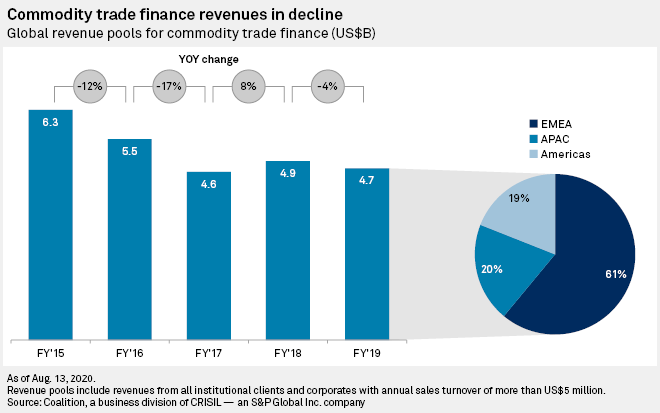

Total commodity trade finance revenues for banks globally dropped 40% year over year in the second quarter of 2020, according to figures from Coalition, an S&P Global-owned research company. For the first six months of the year, they dropped 29%.

"From these revenue figures you can see why, all of a sudden, so many banks [are starting] to review their strategies in this business," said Eric Li, research director at Coalition, in an interview.

ABN Amro Bank NV said Aug. 12 that its trade and commodity finance activities will be "discontinued completely," while other large players are re-evaluating their strategies in the sector.

This type of finance covers lending across the energy, agricultural and metal commodity value chains, from producers to refineries and distributors, as well as financing for the "middlemen," the commodity traders, a space dominated by large trading firms such as Glencore PLC, and Trafigura Group Pte. Ltd.

ABN Amro is one of the most active commodity trade financiers globally, along with Dutch peers ING Groep NV and Rabobank and French banks BNP Paribas SA, Société Générale SA and Crédit Agricole SA.

Its decision to exit the trade and commodity business completely was "shocking," said John MacNamara, previously Deutsche Bank's global head of structured commodity trade finance and now an independent commodity specialist.

"ABN Amro has always been a commodity bank; it's got commodity in its DNA. To see them retire tells you that there is something wrong in the kingdom of commodity trade finance," he said in an interview.

Other industry observers were less surprised.

"I completely understand why some banks decide to pull the plug now," Li said. "Uncertainty in the next 12 to 18 months is huge. We could easily have more big write-downs in these books, if anything bad happens."

ABN Amro is not alone in its hesitation about financing this form of trade. BNP Paribas has suspended new commodity trade finance deals while it reviews its involvement in the business in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, Bloomberg reported in the week of Aug. 3.

It followed reports from the same news outlet that Société Générale is closing its trade commodity finance unit in Singapore following a decision to freeze funding to oil traders in Asia-Pacific after the collapse of trading firm Hin Leong Trading (Pte.) Ltd.

'A perfect storm'

"From a banker's perspective, ABN Amro's decision is unfortunately not surprising," said Jean-François Lambert, founding partner of commodity trade finance consultancy Lambert Commodities, and a former trade finance executive with HSBC. "Banks are reviewing their activities, and commodity trade finance doesn't shine in that review."

Even before the pandemic hit, profit margins for this type of lending had narrowed significantly due to low interest rates and growing compliance costs, leading to "a perfect storm in the making," Lambert told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

In 2019, the total revenue pool for commodity trade finance was $4.7 billion, down from $6.3 billion in 2015, according to Coalition data. For this reason, together with the sometimes high-risk nature of the business, a lot of banks are not involved in commodity trade finance at all, said Li.

For those banks active in the market, a drop in transaction volumes in light of historically low oil prices and a number of high-profile bankruptcies are now making the business look increasingly unattractive.

The collapse of Singapore-based Hin Leong Trading has been particularly painful for lenders. Banks including HSBC Holdings PLC, Standard Chartered Plc, Deutsche Bank AG and DBS Group Holdings Ltd. have a combined exposure of at least $3 billion to the beleaguered oil trader, according to Bloomberg.

And while second-quarter revenue figures look bleak, the worst might not be over. Commodity trade finance still faces "a massive revenue decline" of the kind the industry has not seen in the past couple of years, according to Li.

"Everybody is still waiting to see whether the shale gas industry in the U.S. is going to shut down even further, or whether there's going to be more commodity traders going bankrupt. That risk has not been fully removed," Li said. Even some of the known bankruptcies may not have been fully booked in banks' financial results yet, Li said, as lenders are still attempting to recoup their money.

He said oil prices are unlikely to recover to pre-pandemic levels soon, if ever, meaning industry revenues for commodity trade finance could stay depressed at 2020 levels "for a very long time."

New players

Li estimates that individual banks will see a drop in commodity trade finance revenues of between 25% to 60% by the end of the year, making it increasingly hard for some of them to justify to their shareholders a decision to maintain the business.

As a result, banks around the world will likely follow ABN Amro and decide to reduce their exposure to the commodity sector, said Lambert, although he is hopeful that other financial institutions will not quit the business altogether.

He said banks' decision to withdraw or reduce their commodity trade finance lending could trigger a liquidity squeeze for the sector. The big losers will be the midsize companies, which will struggle to find banking support while cost of funds will increase across the board, he added.

Other players may decide to enter the market and reintroduce commodity trade finance in a "different format," said Li. He added that it takes a bank 12 to 18 months "at a bare minimum" to exit a commodity trade finance portfolio, and only after this "transition period" will it be clearer how the market will be reshaped.

Among the winners are the large commodity trading firms, who still have access to "massive resources" and are increasingly acting as banks by financing their own trades, MacNamara said.

Funds, too, will look to get more business in light of rising prices, MacNamara said, adding that he is being approached on a daily basis by existing funds that wish to move into trade finance.

The number of trade finance funds has been growing in recent years to meet rising demand from institutional investors. Lambert, however, is less convinced that these investors will still see the asset class as an attractive investment in light of recent news.

"Everybody now is reassessing things. And I'm not sure that investors will be so keen to fill the gap," he said.