Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Apr, 2022

By Brian Scheid

Recent protests in Colombo, Sri Lanka, have centered on a growing economic crisis in the country that has caused the government to suspend foreign debt repayments.

Source: Rebecca Conway/Getty Images News via Getty Images

Record debt levels, rising interest rates, surging food and energy prices, and Russia's invasion of Ukraine threaten to spark the worst sovereign debt crisis in 40 years.

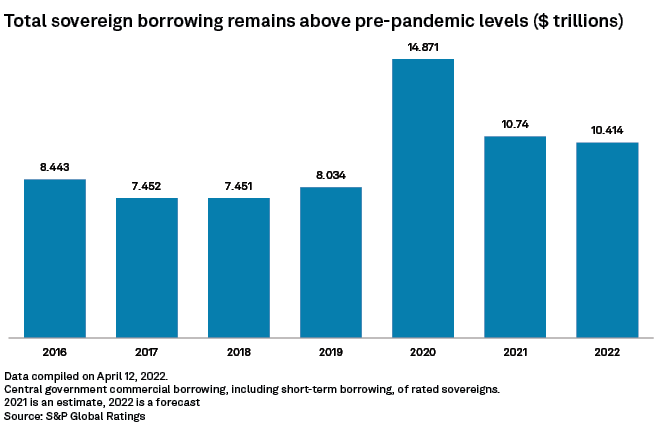

Sovereign government borrowing surged to a record $14.871 trillion in 2020 and will remain above pre-pandemic levels through at least 2022, according to S&P Global Ratings. Governments borrowed heavily to fund measures to ward off the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and are now facing steep cost increases to service that debt.

Those factors risk plunging many countries, especially those in emerging markets that are already teetering near distress, into deeper debt crises later this year. A rush of defaults could push up borrowing costs for affected countries, erode the value of their currencies, crash markets and send inflation higher, potentially leading to deep recessions.

"The pessimistic scenario is that the war gets worse, commodity prices all over the world start increasing further, and you add the new COVID variants that we don't know how to deal with and it's going to get very bad," said Mitu Gulati, a University of Virginia School of Law professor and sovereign debt scholar, in an interview.

If that pessimistic scenario plays out, as many as 30 counties could default, an economic disaster on the level of the Latin American debt crisis, Gulati said. That crisis unfolded as numerous Latin American countries — including Mexico, Brazil and Argentina — racked up record debt from commercial banks and other creditors throughout the 1970s that they were unable to service by the early 1980s.

"We don't really have an international mechanism to deal with a sovereign debt crisis that hits that many countries at the same time," Gulati said.

Modest decline

Sovereign borrowing in 2020 jumped 85% over the prior year as social services expanded by levels not seen in generations to offset the pandemic's economic toll, according to Ratings. The agency estimates borrowing dipped in 2021 and will drop by more than $300 billion in 2022, though the decline is minimal by historical standards as borrowing this year will likely be roughly one-third above pre-pandemic levels.

"That's still a huge amount," said Roberto Sifon-Arevalo, managing director and chief analytical officer for sovereign and international public finance ratings at Ratings.

Borrowing will remain high partly due to the decision by many G-7 and other countries to borrow as much money in as short a time frame as possible in 2020.

Total global debt rose to $226 trillion in 2020, or 256% of GDP, representing the largest one-year debt surge after World War II, according to the International Monetary Fund's latest data. Government borrowing accounted for 40% of total global debt, the highest share in nearly 60 years, according to the IMF.

Government commercial debt stock rose to 73.6% of GDP in 2020, up from 58.7% in 2019, according to Ratings. That debt stock has moderated somewhat but remains well above pre-pandemic levels. Ratings forecasts government commercial debt stock to fall to 67.7% of GDP in 2022.

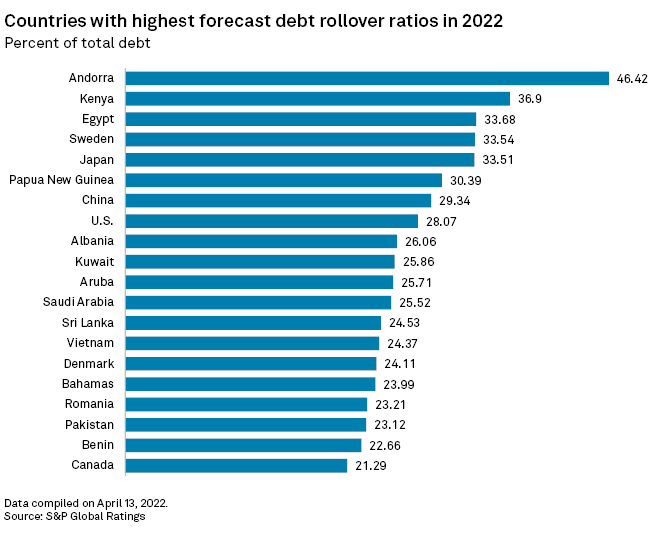

In the U.S., Japan and Germany, short-term borrowing increased to roughly one-third of all borrowing during the pandemic, leaving those countries with a historically large amount of shorter-maturity debt they need to refinance, Sifon-Arevalo said.

The rollover ratio, or amount of maturing debt to be replaced with newly issued debt, is now roughly 27% for G-7 nations, up from 21% in 2019, according to Ratings. The U.S. rollover ratio will be 28% in 2022 and Japan's will be 33.5%.

Borrowing will also remain relatively high through 2023 as governments face a backlash over the removal of some stimulus measures put in place at the height of the pandemic.

Big borrowing appetite

Fuel and food prices are rising worldwide, increasing political pressure for governments to borrow to continue to expand their social safety nets, said Lee Buchheit, a veteran sovereign debt restructurer and honorary professor at University of Edinburgh Law School. In addition, with the war in Ukraine showing no signs of ending, countries will be looking to expand their military budgets.

Central banks are raising interest rates to tackle rising inflation. That will force governments into the "odious position" of having to raise taxes or cut spending in order to pay to service their record-high debt stocks, Buchheit said.

And as debt stocks grow, borrowing could stall.

"At what point does the existing debt stock of a country begin to chill the willingness of investors to continue to lend to that country?" Buchheit said. "At some point, they'll simply stop lending altogether."

Emerging market pains

The cost of borrowing for emerging market economies has already picked up significantly as many central banks in these countries have accelerated monetary policy tightening, largely through rate hikes.

About 60% of low-income countries are near or at a level of debt distress where they are unable to fulfill financial obligations and debt restructuring may be required, according to the IMF. This is up from about 30% in 2015.

Emerging markets have to pay more to service their debts, but are also facing political pressure to use their foreign exchange reserves to continue buying food and fuel as prices skyrocket, Buchheit said.

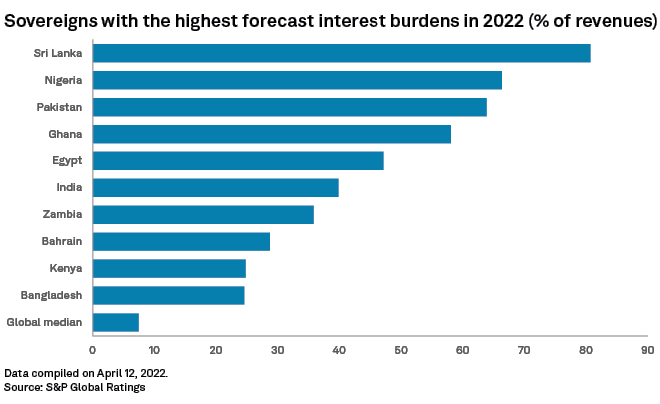

This is playing out in Sri Lanka, which on April 12 announced the suspension of payments on foreign debts amid struggles to import food and fuel as its foreign currency reserves declined. Sri Lanka will face the highest interest burden of any sovereign government in 2022 as nearly 81% of its fiscal revenues will go to interest payments, according to Ratings.

"Sri Lanka is an example of how quickly this can get much worse," said Gulati with the University of Virginia. "Just a couple of months ago that was a relatively manageable restructuring situation. Now, it's like pouring fuel on a small fire."