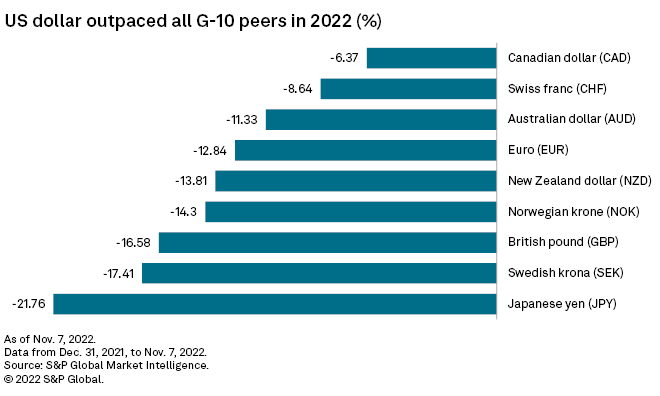

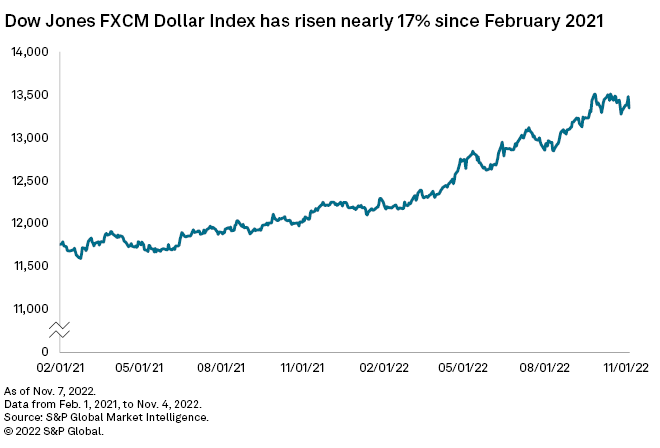

Central banks worldwide are weighing substantial policy efforts to fight against the strongest U.S. dollar in decades, but crushing post-pandemic inflation, imbalanced global economic growth and aggressive interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve are making these efforts particularly difficult.

So far this year, Japan has spent tens of billions of dollars since September on a pair of currency interventions that largely failed to staunch the yen's historic slide against the dollar. Meanwhile, the People's Bank of China's efforts to both raise foreign exchange risk reserves and contain yuan trading within fixing limits have not stopped the currency's relative weakness to the dollar, and Turkey's push to prevent its lira from further slumping has been largely unsuccessful.

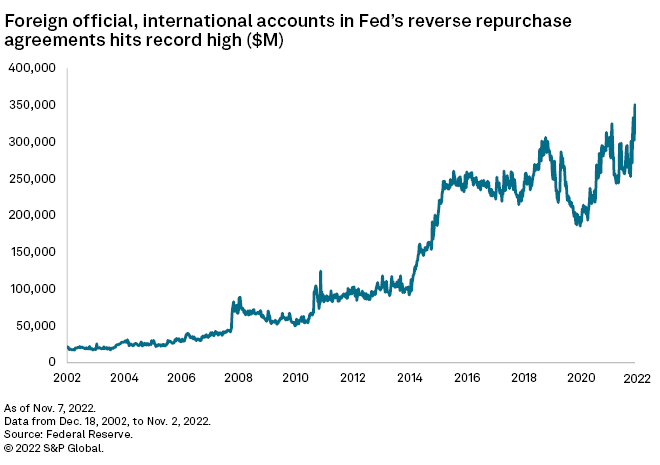

Foreign governments have also poured a record amount of cash into the Fed’s overnight reverse repurchase facility, an indication they could be getting ready to sell dollars soon, one potential intervention aimed at slowing the greenback's historic rally. Still, as their currencies slide and the dollar appears likely to continue to strengthen as the Fed raises rates higher, foreign central bankers have few options outside of letting their currencies weaken further or tightening rates in an attempt to keep the differential with the U.S. from widening further.

"The key theme here is that defending currencies is proving very difficult, at best they're slowing the bleed," said Craig Erlam, a market analyst at OANDA.

Dollar pressure

The strong dollar has caused severe inflationary pressure around the globe, particularly for net importers like Japan. It has also made it more costly for nations to finance their debt.

"At some point they need to defend their currencies against the rising dollar," said Richard Farr, chief market strategist at Merion Capital Group.

In order to put downward pressure on the U.S. dollar and prop up their own currencies, central banks would likely sell available dollars first. In one possible preparation for this, foreign central banks have moved hundreds of billions of dollars into reverse repurchase agreements with the Fed, which allow them to both invest dollars and keep them close at hand if they deem selling them necessary. Through these so-called reverse repo agreements, the Fed sells securities and buys them at a higher price the next day.

Foreign official and international accounts in reverse repurchase agreements reached a record $350.74 billion on Nov. 2, according to the Fed's latest data.

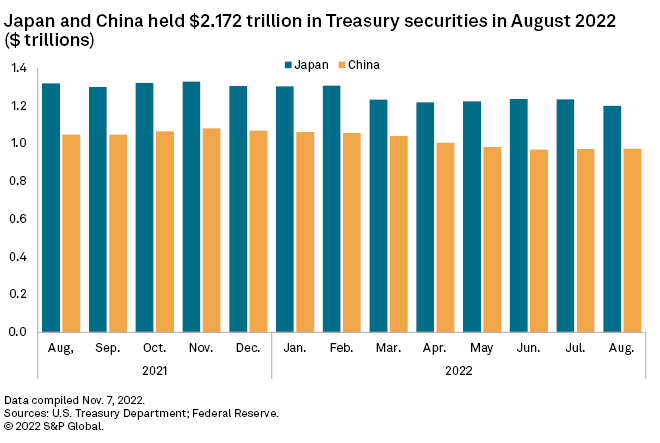

Foreign central banks may also look to sell off some of the trillions of dollars worth of Treasury securities held by their governments.

This is likely the path the Bank of Japan pursued in its recent interventions to attempt to prop up the struggling yen by selling off its foreign-exchange reserves, Farr said.

As of August, Japan was the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasury securities, with $1.200 trillion. This is $119.9 billion less than Japan held a year earlier, according to U.S. Treasury and Fed data. Foreign governments held a total of $7.509 trillion in Treasury securities in August, down $69.8 billion from a year earlier.

"In general, foreign central banks have stopped buying Treasuries on net and have mildly reduced their Treasury exposure, which is what we normally see in rising dollar environments," said Lyn Alden, an independent investment research provider.

China's Treasury holdings fell to $971.8 billion in August from $1.047 trillion in August 2021, while the U.K., the third-largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasurys, increased its holdings to $644.7 billion from $568.9 billion over that time.

Varied defenses

Not all currency defenses look the same, Alden said. Brazil, for example, responded early with significant interest rate increases, but that is a less tenable path for foreign developed countries with significant debt levels. The Brazilian real has gained about 8.9% on the dollar since the start of this year.

"In the current volatile and uncertain environment, short-term rate differentials do not drive the majority of currency moves, risk sentiment does," said Francesco Pesole, a foreign-exchange strategist at ING. "So we think efforts to help local currencies by central banks would need to require targeted FX interventions to prove successful."

Previously, a strong dollar has resulted in widespread insolvency throughout regions, such as in Latin America in the 1980s or Southeast Asia in the late 1990s, Alden said.

That may not prove the case now, as the largest emerging market countries have built up relatively significant reserves, Alden said.

China holds roughly $3.052 trillion in foreign-currency reserves as of October, the most in the world, while Japan is second with $1.078 trillion, according to government data.

With reserves of this size, intervention from central banks could result in "at least slowing" a foreign currency's slide against the dollar, said Derek Halpenny, head of research at MUFG. Still, the impact of any intervention may prove limited.

Higher rates

Foreign currencies are unlikely to gain much traction against the dollar until the Fed begins easing from its aggressive pace of tightening through rate hikes.

"Other central banks can probably slow the advance of the U.S. dollar as the Bank of Japan has done, but the direction of travel is likely to remain the same unless we get a sign that the Fed is looking at coming to the end of its hiking cycle," said Michael Hewson, chief market analyst with CMC Markets. "The only clue as to when that might happen is how the U.S. economy performs between now and the end of the year."

On Nov. 2, the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee approved its fourth-straight 75-basis-point interest rate hike as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that talk of a pause in hikes was premature, indicating that a pivot in policy may not take place until well into next year.

If the Fed remains hawkish, this means the U.S. dollar's recent strength may not peak until the first quarter of next year, Halpenny with MUFG said.

"There remain compelling evidence that [foreign exchange] intervention without a shift in the fundamental backdrop that drove [foreign exchange] rates, the chances of success are limited," Halpenny said.