Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

2 Aug, 2022

|

East Coast cities like Burlington, Vt., are using several policy pathways to restrict the use of natural gas and other fossil fuels in new buildings. |

Three years after the unofficial start of a movement to prohibit natural gas use in new buildings, West Coast-style policies are gathering momentum in the Eastern U.S.

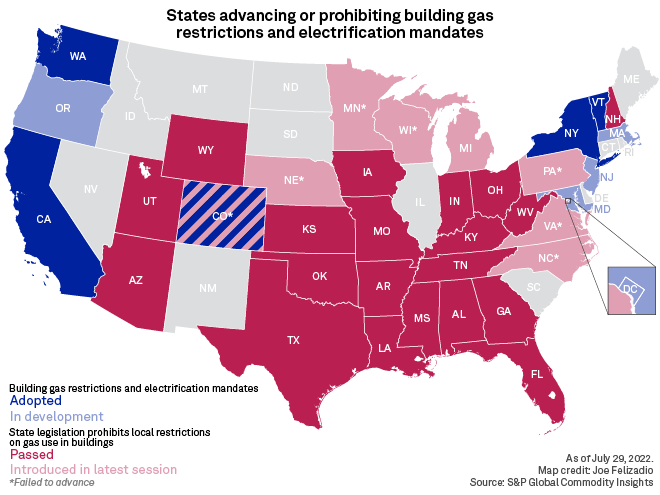

Strategies to require building electrification advanced in New England and Washington, D.C., while an effort to prohibit local gas bans failed in Pennsylvania, the nation's second-largest gas-producing state. Even as statewide gas ban legislation died in New York, policymakers created new opportunities to tackle building electrification.

Meanwhile, this type of policy continued to expand in California, Oregon and Washington. Headlining the developments, Los Angeles lawmakers signaled that they will likely restrict gas use in buildings in the nation's second most populous city.

And capping off several months of building decarbonization activity, the U.S. Senate surprised the nation with a last-minute climate and clean energy spending package, with billions of dollars allocated to building electrification and energy efficiency.

Massachusetts poised to pilot gas bans

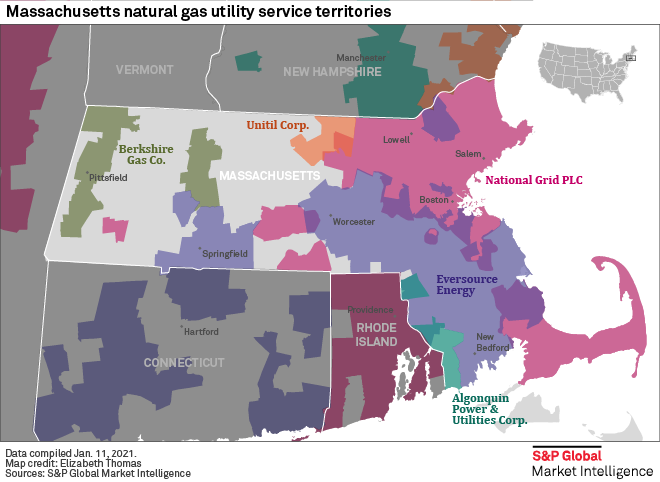

Some Massachusetts towns and cities could finally get permission to ban new gas hookups following a multiyear campaign. The Massachusetts Legislature passed a compromise climate bill that directed the state Department of Energy Resources, or DOER, to establish a demonstration project that would allow up to 10 cities and towns to pass ordinances or bylaws that restrict fossil fuel use in new construction.

Lawmakers included the provision after several setbacks for building electrification advocates. The attorney general has twice overturned gas ban bylaws in Brookline, Mass. A voluntary energy code proposed by the DOER frustrated climate activists because it did not fulfill state lawmakers' intention to give local governments explicit authority to restrict gas use in new construction.

The demonstration projects would require local governments to pass an ordinance or bylaw and secure authority from the state legislature to prohibit gas use, a process some towns and cities have already started. The DOER would have to collect data on the gas bans' impacts on emissions and building and operating costs. Utilities would additionally compare electric and gas consumption and customer bills in participating towns and cities with a sample of nonparticipating municipalities.

Also in Massachusetts, the DOER released draft stretch energy code updates that encourage and in some cases require building electrification. Meanwhile, the state's Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs established emissions limits for building heating and cooling through 2030. Remaining within the limits will require rapid adoption of electric heat pumps, the agency said.

Vermont reboots building electrification agenda

Lawmakers in Burlington, Vt., expanded an ongoing effort to decarbonize new buildings after receiving broader authority from the state to regulate building emissions. The Burlington City Council on May 2 asked the city's municipal electric utility to also explore decarbonization pathways for existing commercial buildings, major renovations and city-owned property.

In 2021, Burlington sought authority to place a carbon fee on new buildings that choose to connect to fossil fuel infrastructure. That policy is still under consideration, but the Burlington Electric Department, or BED, also proposed expanding its primary renewable heating ordinance, adopted in June 2021 as a companion policy to the carbon fee.

|

* Access more details on energy and utilities news. * Access more details on retail gas sales by sector and state. |

The ordinance requires new commercial buildings to meet at least 85% of their design heating load with renewable energy, including electricity, wood or biogas. The ordinance currently only applies to space heating, but the city could expand it to water heating, clothes drying and cooking, BED said in a July 11 report.

To decarbonize existing commercial buildings, the utility is exploring building performance standards, which require owners to achieve emissions reductions or efficiency gains. BED has explored performance standards adopted in Boston and New York, as well as a Denver policy that also requires building owners to replace end-of-life gas equipment with electric alternatives when cost-efficient.

Anti-gas ban movement suffers defeat in Pennsylvania

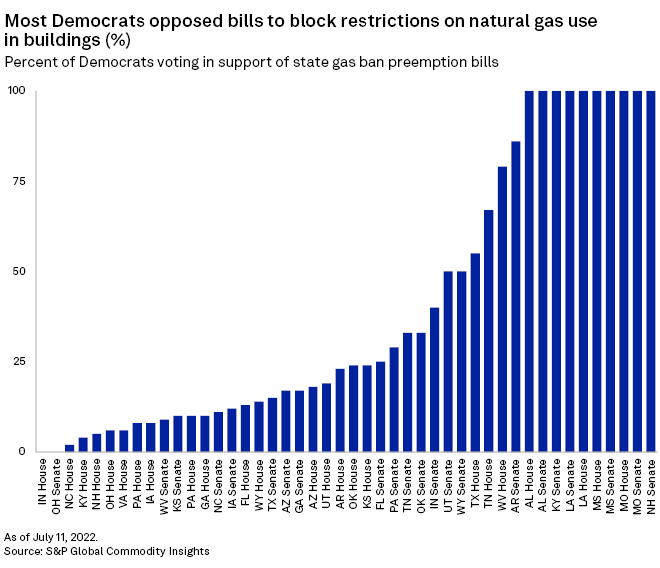

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf on July 11 became the second Democratic state executive to veto an anti-gas ban bill. The move reflected Wolf's ongoing differences with statehouse Republicans over climate policy and offered more evidence that such legislation faces headwinds in politically divided states.

The bill attracted little support from state Democrats, leaving supporters without a veto-proof majority.

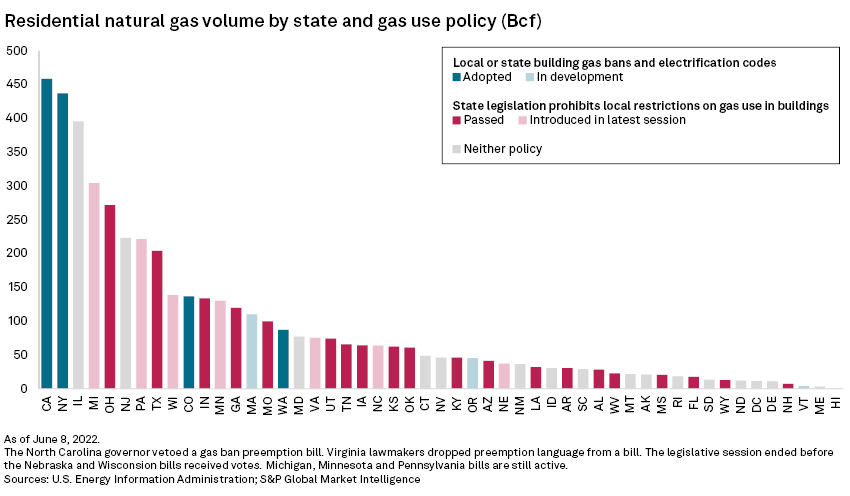

Introduced in February 2021, Senate Bill 275 would have preempted any municipality from passing a policy that restricts access to utility service based on fuel type. Similar legislation has passed in at least 20 states, where proponents say the laws preserve consumer fuel choice.

Wolf sided with the policy's opponents — chiefly Democrats — who say the bills strip local governments of their ability to set energy and climate policy. The governor also said the bill was "overly broad and sweeping," which could bring unintended impacts and litigation.

"Specifically, the legislation would limit the tools available to local governments to address the global threat of climate change in future years and stands in the way of clean energy incentives and initiatives," Wolf said in a statement.

Pennsylvania is one of the nation's top gas consumers for building end uses. If the legislation had become law, states with preemption bills would have accounted for 35% and 37% of the nation's residential and commercial consumption, respectively. Currently, such laws protect gas use in states that make up 30% and 33% of residential and commercial demand, respectively.

Similar legislation died in committee in Minnesota, another large gas consumer, when the state legislature adjourned in May before several preemption bills got a full chamber vote.

Federal, district electrification efforts advance in Washington

The federal government is poised to invest heavily in building electrification following a sudden reversal on climate spending by Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va. The Inflation Reduction Act includes $9 billion in rebates over 10 years for building electrification and energy efficiency retrofits, as well as tax credits for heat pump purchases and funding to bolster U.S. heat pump manufacturing.

Also at the federal level, Senate Democrats proposed incentives for U.S.-made electric heat pumps in May. In June, the U.S. Department of Energy announced a potential breakthrough in cold climate heat pump performance and proposed a tougher gas furnace efficiency rule. In July, the DOE detailed a program to help states and cities update their building codes and adopt policies that could support electrification.

In Washington, D.C., the district's legislative body passed a bill that would prohibit on-site combustion of fossil fuels in new commercial construction by 2027. The legislation mirrored proposals that are advancing through the district's building code update cycle, which would require all-electric residential and commercial construction in D.C.

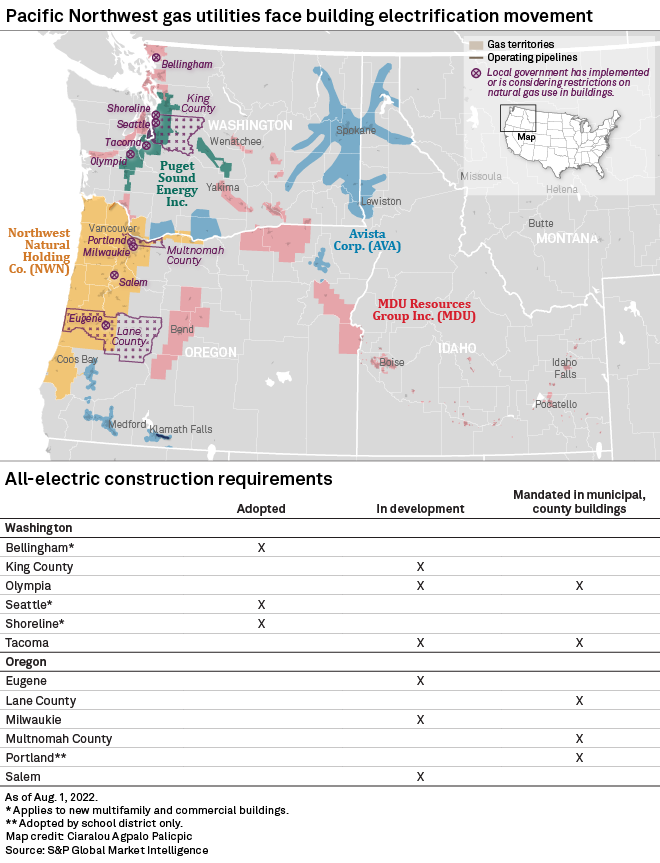

The D.C. proposals offered more evidence that policymakers and stakeholders plan to use building codes to mandate building electrification. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul signed legislation July 5 that aligns the state's code update process with its climate goals. The Washington State Building Code Council on June 29 advanced proposals that would require electric heat pumps in low-rise residential buildings. Washington recently adopted electrification mandates for new commercial buildings.

Eugene, Ore., to draft gas ban

Local lawmakers in Eugene, Ore., took another step toward prohibiting fossil fuel use in new buildings and set in motion a plan to decarbonize the city's existing building stock.

On July 27, the Eugene City Council voted 5-3 to direct the city manager to draft a fossil fuel ban for new residential buildings that would go into effect in June 2023. The council directed staff to schedule a public hearing for the fall.

During an earlier work session on July 25, Councilor Claire Syrett moved to have the city manager also draft an ordinance prohibiting fossil fuels in new commercial buildings by June 2024. Councilors instead voted 7-1 on July 27 to hold another work session in the fall to discuss a commercial ordinance, including waivers for hard-to-electrify buildings and end uses.

Council members also directed the city manager to formalize a goal in Eugene's Climate Action Plan to decarbonize existing residential and commercial buildings by 2035 and industrial facilities by 2050. In a related motion, councilors asked staff to develop a public outreach plan, with a focus on engaging historically marginalized communities.

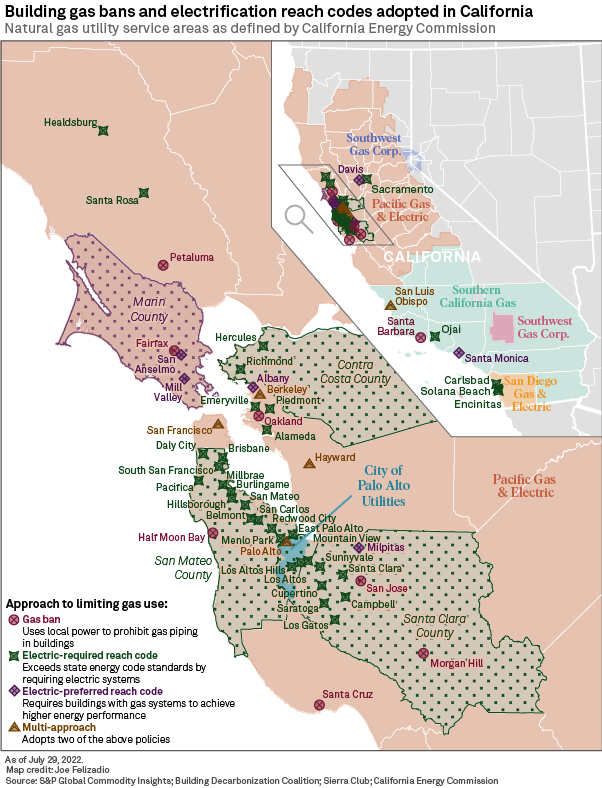

57 electrification ordinances and counting in California

While the biggest West Coast news was Los Angeles's move to require zero carbon emissions in new buildings, cities across California continued to adopt and expand electrification mandates, bringing the Golden State tally to at least 57.

San Mateo County added another two electrification codes in recent months. San Mateo is one of the two counties in the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area that together account for about half of the state's ordinances in this category.

The Belmont City Council on June 14 adopted all-electric requirements for new residential and nonresidential buildings and gut renovations. The reach code allows fuel gas where electrification is not feasible, as well as for space conditioning in laboratories, clothes drying in hotels, and cooking in restaurants that demonstrate a need for combustion equipment. Buildings that receive exemptions must include electric wiring and paneling for future conversion from gas.

Lawmakers in Hillsborough, Calif., on April 11 adopted a narrower reach code that applies to low-rise residential buildings. It prohibits propane and gas use for space and water heating, establishes a preference for electric clothes drying and cooking, and requires pre-wiring for electrification if gas dryers or ovens are installed.

Elsewhere in the Bay Area, the Hercules City Council on June 14 required all-electric construction, including major renovations, for residential buildings, guest houses, hotels and offices, with exceptions for laboratories and emergency facilities and generators. Hercules became just the second city to pursue the policy in Contra Costa County, taking action after the county adopted an electrification code for unincorporated areas in January.

Finally, on California's Central Coast, the San Luis Obispo City Council on July 19 voted to prohibit gas infrastructure in new buildings, expanding on a previously passed electric-preferred reach code. The ordinance includes indefinite exemptions for backup power for critical infrastructure and process loads in industrial facilities, as well as a carveout for commercial kitchens that expires after 2025.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.