Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

1 Dec, 2021

|

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell announced the bank will begin to taper its monthly $120 billion bond purchases from November. Source: Getty Images North America |

The Federal Reserve may never be able to fully extricate itself from a Treasury market that is now too big for traditional liquidity providers to meet demand in times of stress.

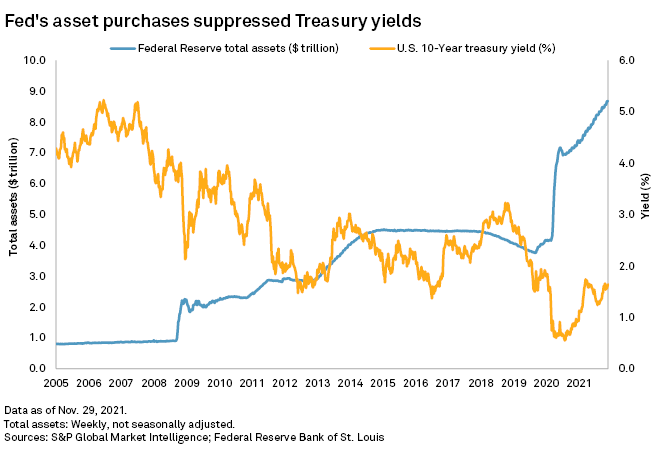

The Fed has been a major buyer of government bonds since March 2020, when financial markets froze in the face of COVID-19. The central bank is now cutting back its monthly $120 billion of purchases of Treasurys, Treasury inflation-protected securities and mortgage-backed securities by $15 billion each month.

If the Fed sticks to the plan, the tapering program would finish in June 2022, by which point the Fed's balance sheet will reach over 36% of GDP, according to Paul Gruenwald, chief economist at S&P Global Ratings.

But experts say it is inevitable that in periods of market stress the Fed will again be called upon to be a buyer of last resort, given the sheer size of the Treasury market — the largest in the world, worth about $23 trillion — and a shift in the nature of market makers, or providers of liquidity, away from large banks.

"Until [the Fed] finds a workable solution — which they're nowhere near — they're going to have to be a presence, whether actively, or to let the market know that they are on standby," Shane O'Neill, head of interest rate trading for Validus Risk Management, said in an interview.

The Fed has made adjustments to its repurchase operations so that it can temporarily step in to buy Treasurys from domestic and foreign holders in times of market stress. Still, there are no solutions that do not involve the Fed providing a backstop of liquidity.

The SEC has called for a centralized clearinghouse to manage risk, and there are plans for improved data quality. Bank of America said in a November report that, while helpful, such measures are "insufficient to address U.S. Treasury market ills."

Safe haven asset

Treasurys are the benchmark against which assets such as corporate bonds are priced. A liquidity crisis typically sends borrowing costs for companies spiraling and hits the value of stocks as investors off-load riskier assets.

The U.S. government debt market is the most liquid in the world, with an average of $620 billion traded each day in the week of Nov. 15. The ability to easily buy or sell U.S. debt makes it the ultimate safe haven asset for investors.

But that liquidity cannot be depended on as it once could. The Fed has been forced to step in on three occasions since 2014 when liquidity has evaporated, buying trillions of dollars of bonds to stabilize the market and to prevent a spike in borrowing costs.

"The fact that [a liquidity crisis] is a risk is borderline unacceptable for a working financial system," O'Neill said. "It stops the flow of capital. It stops the flow of credit."

The latest rupture in the Treasury market was the result of COVID-19. Panic about the economic implications of widespread lockdowns led investors to dump stocks, corporate bonds and even safe haven government bonds.

The Fed was forced to step in with $1.5 trillion in emergency quantitative easing in just seven weeks to bring yields down and keep the market working.

"The flight to safety was so extreme that they even ran out of Treasurys and into the ultimate safety of the U.S. dollar," John Canavan, lead analyst at Oxford Economics, said in an interview.

A similar crisis occurred in September 2019 in the repurchase agreement, or repo, market, the function for short-term lending between banks. The repo rate — the cost to borrow — spiked as the number of borrowers requiring overnight cash exceeded the number of lenders. The Fed then flushed liquidity into the market to stabilize the rate.

Market makers

Both shocks are consequences of a structural problem in liquidity provision that has grown in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008-2009, according to research by the Bank for International Settlements, or BIS.

Traditionally, large banks acted as market makers, buying and selling Treasurys. Bank dealers offer secure liquidity as they take long and short positions over long periods and have obligations as market makers to provide liquidity.

The introduction of capital requirements for banks and other regulations in the wake of the 2008-2009 financial crisis meant banks had less room on their balance sheets for market making, while ballooning government spending meant there was a sharp increase in the amount of debt that needs to be absorbed.

This has pulled other actors into the fold, such as high-frequency traders, which are drawn to highly liquid markets but "tend to shrink their balance sheets when funding becomes more expensive or less available," according to the BIS.

High-frequency and algorithmic traders now account for about 50% to 60% of the volumes of the interdealer broker market, according to Treasury officials.

"Those bots are very useful at times at providing liquidity, but it can be illusory," O'Neill said. "When there's a panic, it just disappears and you're left with the 24 or so primary dealers to handle the fallout."

The long Treasury exposures of hedge funds fell by $242 billion in March 2020, according to the BIS, which suggested the deleveraging could have been even more extensive had the Fed not stepped in.

"It's clear that with the exceptional increase in size, things are different than they were," Canavan said. "In times of greater stress, the Fed will have to take a larger hand than it has historically."

Volatility is increasing

Some measures of volatility are already rising as the Fed tapers. The MOVE index, a measure of volatility in the U.S. Treasury market — the bond market's equivalent of the VIX — has risen to its highest level since March 2020 as liquidity has drained.

"We expect a reduction in liquidity and an increase in real rates to reduce investor risk appetite," said Viktor Hjort, global head of credit strategy at BNP Paribas. "Demand for corporate bonds will be vulnerable to the taper liquidity drain."

Lack of demand for a November auction of 30-year government bonds was described as "disastrous" by Althea Spinozzi, fixed income strategist at Saxo Bank, while bid-ask spreads in the two-year and five-year Treasury markets have also widened, suggesting fewer market makers competing for business.

The lack of liquidity is spreading.

"It definitely is bleeding into other markets," O'Neill said. "Liquidity in sterling and euro markets [has] been absolutely terrible in the last few months."

Oxford Economics' Canavan believes rising inflation may accelerate the Fed's taper and predicts a bumpy road ahead for the Treasury market.

"I don't think what we saw in 2020 will be a common feature of the market going forward," Canavan said. "We need to get used to a little bit more volatility."