Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

8 Dec, 2021

An Amazon employee assembles a mobile drive unit in one of the company's manufacturing facilities

in the Boston area.

An accelerated move to automation during the pandemic prompted many e-commerce retailers to rethink business processes and retool jobs in critical areas such as final assembly, last-mile delivery and customer service, retail experts say. Even so, the industry is still in dire need of more human workers.

Companies ranging from global enterprises like Amazon.com Inc. to small, family-owned grocers are rolling out enhanced benefits to help attract and retain employees, but labor experts say easing the transition to a partially automated supply chain also requires lots of communication, worker accommodations and targeted retraining opportunities.

That is easier said than done in a tight labor market where thousands of employees are quitting retail jobs in search of new opportunities. According to the U.S. Labor Department's most recent employment data, there were 10.4 million open positions across industries in September, including about 1.1 million in retail. That is up from 7.1 million job openings in September 2019, before the pandemic, including 740,000 in retail.

"You're going to have robots that will do low value-add tasks — pulling product off shelves, or moving products around the location," said Tyler Higgins, retail practice lead and managing director at consulting firm AArete. "Robots can do final assembly, but someone has to make sure it's going out the door in the most efficient manner."

Ahead of the busy holiday sales season, Amazon in September announced plans to add 125,000 fulfillment and transportation employees. Walmart Inc. said that month it planned to hire 150,000 new U.S. store associates as well as 20,000 supply chain associates in roles including order fillers, freight handlers, lift drivers and managers. Target Corp. said it planned to hire 100,000 workers in the fourth quarter and provide more pay, flexibility and reliable hours for existing employees.

All three companies are offering extensive perks and education programs to help keep human workers on board long-term.

Automation adoption

Many retailers turned to robotics to keep up with e-commerce fulfillment demands during the pandemic.

North American companies ordered 9,928 robots valued at about $513 million in the third quarter, with both metrics about a third higher than the same period a year ago, according to the Association for Advancing Automation, a robotics trade group. Walmart, for instance, announced plans in July to partner with Symbotic LLC to pilot a new robotics system that sorts, stores, retrieves and packs freight onto pallets. Walmart did not disclose the cost of that investment but said in a press release that the new way of unloading store-friendly palletized trucks will "make the process faster and simpler for our associates, allowing them to spend more time with our customers."

|

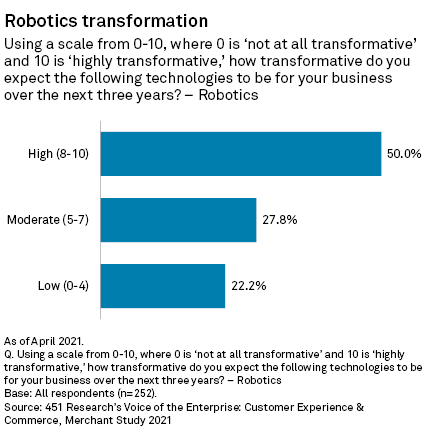

The pace of the automation rollout is not expected to slow any time soon, as more companies turn to robotics to help improve operational efficiencies. 451 Research's most recent merchant survey found that the majority of respondents (about 78%) believe robotics technologies will be moderately to highly transformative to their businesses over the next three years. The survey respondents were technology decision-makers in sectors including retail, grocery, home improvement and hospitality.

Large retailers like Walmart and Amazon are among those furthest along in the automation process, and their experiences show that human workers remain essential to operations. Amazon, which bought robotics company Kiva Systems for $775 million in 2012, has added more than 1 million new jobs such as maintenance technicians and flow control specialists since making that purchase. Amazon employees today work alongside robotic "drive units" that pick up shelves of products and deliver them to workstations where workers retrieve or stow items.

Amazon did not respond to an inquiry about whether the company has had any difficulty with helping employees make the transition to new jobs that require working alongside automated systems. But company officials did say Amazon regularly looks at its operations and evaluates how it can best utilize technology to create new solutions for employees. "In the case of picking, items come directly to employees where high-judgment is needed," according to Amazon.

Meanwhile, many small retailers like grocers that lack the means for major robotics investments are turning to specialized partners as they launch automation.

Takeoff Technologies Inc., which builds automated microfulfillment centers for grocers such as Albertson's LLC, Big Y and ShopRite, is seeing clients shift grocery store associates to work within the centers, where they pick specific items for a customer's grocery order that are later picked up by an Uber driver or a delivery truck, said Curt Avallone, chief business officer for Waltham, Mass.-based Takeoff.

Avallone said Takeoff's clients find that human workers enjoy the jobs within the centers partly because they are more insulated from the COVID-19 health concerns and customer complaints common on the grocery store floor. The companies also benefit from human workers handling more delicate merchandise. "We don't want to squeeze the tomatoes too much," Avallone said. "A robot could damage them."

Inside a Takeoff Technologies microfulfillment center, grocery employees pick items out of totes and assemble them into orders ready to be delivered in the larger totes below.

Sometimes experiments in automation underscore the continuing value of human workers. Walmart last year ended its contract with Bossa Nova Robotics for shelf-scanning robots after finding that its workers provided similar results to the machines. Walmart did not return inquiries about the decision, but Michael Baker, managing director with D.A Davidson, said part of the problem may have been worker or customer pushback to the sight of robots scanning shelves. Walmart remains the largest private sector employer in the U.S, with about 1.6 million workers, and many of those workers are also Walmart customers.

"I could see that there might be some negative pushback — I think that's all part of the calculus," Baker said.

Human resources

Unclear communication on how automation will affect jobs can prompt employees to look for work elsewhere, labor experts say.

"Many workers are worried about what automation is going to imply for their jobs," including whether it will involve losing autonomy and increased surveillance, said Daron Acemoglu, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who studies automation and its impact on labor. Companies can assuage workers by treating them as "a human resource, not just a cost item," Acemoglu said.

"That would imply making accommodations for the workers — choosing technology not just to squeeze the workers out but to become more productive," Acemoglu said.

Though companies cannot control whether employees choose to leave an organization, they can get ahead of the rumor mill by articulating a clear strategy on how automation will coexist with human workers, said Dani Johnson, co-founder and principal analyst for RedThread Research, a research and advisory firm focused on human capital issues.

"We know that it is much cheaper to reskill people than it is to hire new people; we also know that it is slower," Johnson said. "So if organizations can get ahead of it and say 'this is coming down the path and we don't need as many people doing this thing,' let's start messaging to them now and get them to the right places in the organization and get them the skills they need so we can move them and leverage them somewhere else."

Companies that accommodate worker concerns early on will have a competitive advantage if they provide employees with appropriate breaks, attractive wages and autonomy over their schedules, said Andy Challenger, senior vice president with Challenger Gray and Christmas Inc., an outplacement firm that works with large retailers. To help recruit talent, Amazon has raised wages to $18 per hour for new U.S. warehouse worker hires. Walmart earlier this year raised its starting wage to $12 from $11.

"It's creating an environment and a way of working that is consistent with the way people want to work in this post-COVID era," Challenger said. "There has been a shifting of the way people think about work. Employers that don't recognize that quickly enough are going to fall behind."