Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

6 Sep, 2022

By Michael O'Connor and Umer Khan

The U.S. and China reached a deal that is the first step toward allowing American inspections of the financial records of Chinese companies.

An agreement to allow U.S. scrutiny of Chinese accounting firms would bring greater transparency to financial markets and avoid the potential delisting of more than 200 Chinese companies traded on U.S. exchanges.

The U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, which inspects and investigates public accounting firms around the world, announced Aug. 26 an agreement with the China Securities Regulatory Commission and China's Ministry of Finance to allow inspections and investigations of registered public accounting firms headquartered in mainland China and Hong Kong.

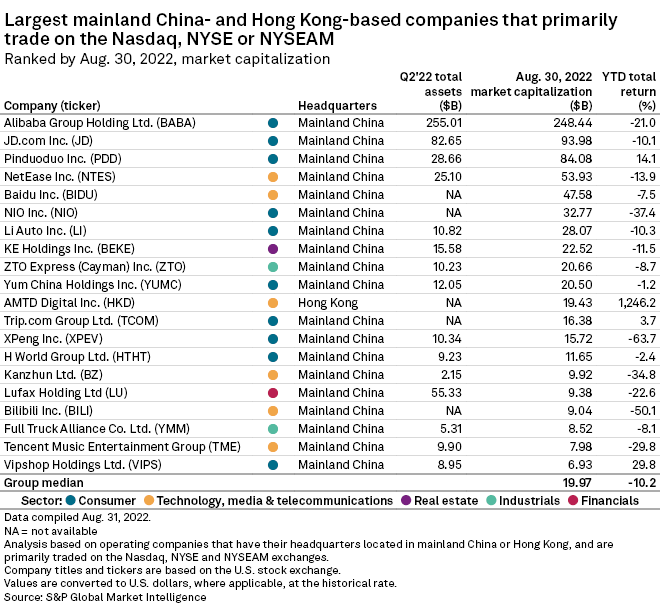

There are 264 public companies headquartered in China or Hong Kong and trade on U.S. exchanges, including well-known e-commerce players Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. and JD.com Inc., in addition to restaurant franchisee Yum China Holdings Inc. The group has a combined market cap of $870.09 billion as of Aug. 30, representing 1.9% of companies listed on the Nasdaq, NYSE and NYSEAM, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Alibaba, JD and Yum China are among the first set of companies to be targeted for audit inspection by the U.S., Reuters reported Aug. 31, citing unidentified sources. The companies and the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board did not respond to requests for comment from Market Intelligence.

The agreement, hailed as a milestone in U.S.-China relations, reduces the chances companies will delist from their U.S. exchanges and, if successful, would give investors greater confidence in their financial statements, experts say. If the agreement succeeds, then investors can have greater confidence the financial statements of Chinese companies listed in the U.S. are consistent, transparent and validated by U.S. regulators, and the deal could lead to further US-China collaboration on market-related matters, said Michael Arone, chief investment strategist for State Street Global Advisors.

"It supports the idea that China and the Chinese government are willing to play by the rules of the global capital markets," Arone said. "That would be a net positive for the Chinese economy and the currency."

Should the deal fall apart, Chinese companies risk their stocks being removed from U.S. exchanges, and both countries would experience relative setbacks to their interests. The U.S. would likely avoid larger risks to the financial system should the deal crumble. Still, the country could take a reputational hit to its status as having highly liquid, transparent and stable capital markets, and China risks losing some access to offshore capital markets, Arone said.

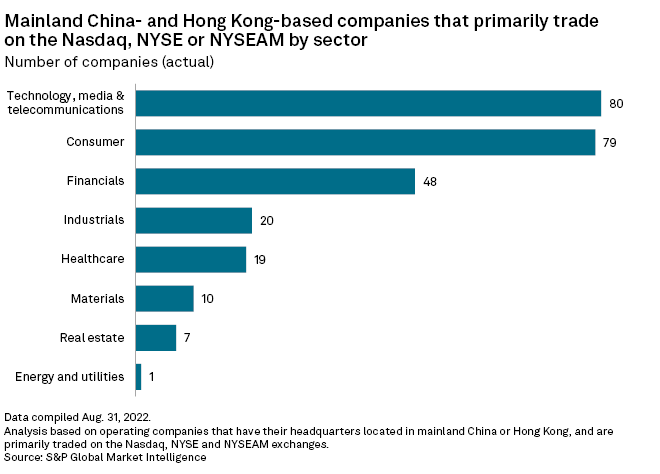

Among the companies subject to the agreement are 80 technology, media and telecommunications companies, 79 consumer companies and 48 financials companies. If these companies delist, they would lose access to capital markets in the U.S. and the prestige of being listed publicly in the U.S., Liu said.

Being delisted would likely have a severe negative impact on the affected companies' valuations, said Zongyuan Zoe Liu, a fellow for international political economy at the Council on Foreign Relations. U.S. shareholders, especially some institutional investors that are prohibited from holding unlisted companies, would have to sell their shares, Liu said. If companies delist in the U.S., they could be delisted, voluntarily or otherwise, from exchanges in other countries but could still opt to list in European markets, Liu said.

"Being delisted from U.S. exchanges does not mean Chinese firms have no other options," Liu said.

Clear disagreement

In public comments about the deal, U.S. officials have emphasized how the agreement allows its regulators to choose whichever firms it wants to inspect without consulting Chinese authorities. By contrast, China has said U.S. regulators would have to go through Chinese authorities to do their audits, according to Liu.

"That's clear disagreement," Liu said.

Given the fraught politics, there is plenty of skepticism about the potential for the deal.

"I think any agreement is almost unenforceable given the tight control with which the Xi regime and the Chinese Community Party want to control data on its citizens and do not want that data in foreign hands," said John Freeman, vice president at CFRA Research.

For more than a decade, U.S. regulators have been obstructed from inspecting registered public accounting firms in mainland China and Hong Kong. Under legislation passed by Congress in 2020, Chinese companies audited by such accounting firms faced the potential of being prohibited from trading on U.S. markets if U.S. regulators determined that Chinese authorities were blocking inspections. The U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board determined last year that Chinese authorities were completely blocking their inspections, but the new agreement requires a reassessment of that determination by the end of this year.

Markets should know soon if the deal is working out, Arone of State Street Global Advisors said. The first companies chosen for inspection will be an important signal about the future of the agreement. If the U.S. picks a company that has sensitive data that could threaten China's national security, tensions could flare and the success of the deal becomes less likely, Arone said. Picking a more straightforward company would suggest a willingness between the U.S. and China to collaborate and find common ground, Arone said.

Further integration of financial markets in the U.S. and China would help relations between the two superpowers, Liu said.

"Financial engagement is ultimately good for peace and stability between two countries," Liu said.