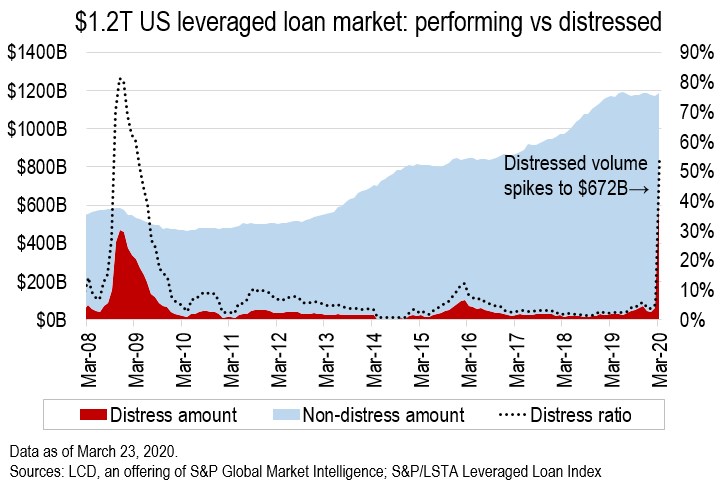

With financial markets across the globe tumbling over the past month, the volume of U.S. leveraged loans priced below 80 cents on the dollar — a widely accepted level indicating distress — has exceeded the 2008 crisis-era distress peak for the first time. The current landscape, however, is notably different from 2008, both for better and worse.

In this analysis LCD looks at the current crisis, and its predecessor, as well as shifts that could impact leveraged loan market liquidity and valuations during the next downturn.

Market size

This month’s historic plunge in the U.S. secondary loan market pushed the volume of outstanding debt priced below 80 to $672 billion at Monday’s close, an increase of over 50% from Friday’s close and outpacing the prior record of $472 billion, set in 2008, by 40%.

|

In today's $1.2 trillion leveraged loan market, the volume of loans below 80 represents a "distress" ratio of 54%, compared to 81% at the 2008 distress ratio peak, when the size of the market was $594 billion (indeed, when the size of the market was less than the volume priced below 80 at Monday's close).

While the absolute numbers are high, we are still well short of an 81% distress ratio — in today’s market, that would amount to almost $1 trillion of distressed loans in the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index.

CLOs/investor base

In addition to market size, one of the biggest shifts during the bull-run was the increasing dominance of CLOs as the primary buyer of institutional leveraged loan paper in the primary market. According to LCD, CLOs accounted for 71% of allocations in 2019, compared to 52% at the 2008 distressed peak.

|

This is important, as CLOs typically are sticky in terms of limited forced selling, with most not required to mark-to-market. While there are limitations on characteristics such as ratings of the collateral (a typical CLO can only hold 7.5% of the collateral pool in triple-C debt), plummeting prices in the secondary do not force CLO asset sales.

This should help limit the vicious cycle that develops when managed accounts or retail funds are forced to sell assets in order to raise cash for outflows. This, in turn, causes further underperformance of loans, leading to more outflows, and so on.

However, while CLOs are typically not forced to sell, they are unlikely to be buyers en masse of distressed debt, and are far from being the buyer of last resort. This is because CLOs often include specific provisions when purchasing assets below a documented threshold price, typically 80, sources explain, with these assets referred to as Discount Obligations, or DO.

Criteria around buying DO vary from CLO to CLO, but tend to center on the amount of DO that can be bought, and a limitation on the lowest price they can be bought at, typically 60.

CLOs are disincentivized to buy DO assets, as well, as such assets must be carried at their purchase price in the calculation of par coverage ratios, meaning for the CLO there is no par benefit to coverage ratios.

Downgrades

As noted above, CLOs can come under significant pressure due to loan downgrades, with most only being able to hold 7.5% of the collateral pool in triple-C debt, while B– rated paper with a negative outlook is treated as triple-C for a CLO’s WARF test (weighted average rating factor), although the debt does not fall into the triple-C bucket.

Once the triple-C basket limit is reached, the excess loans will see a haircut to their par value for overcollateralization tests, which can divert interest payments away from CLO equity and junior tranches.

As of early March 2020, the average CLO transaction had 4.8% exposure to issuers rated CCC+ and below and 3.8% of cushion in their junior overcollateralization tests, S&P Global Ratings notes.

“We expect corporate ratings activity on issuers affected by the coronavirus to continue, and perhaps even accelerate, as the situation continues to evolve. If the pace of negative corporate rating actions increases, we see downgrade risk for some CLO subordinate tranche ratings, and potentially, some BBB tranche ratings,” S&P Global Ratings researchers wrote.

Moreover, S&P Global Ratings believes measures to contain the COVID-19 virus have pushed the global economy into recession and could cause a surge of defaults among nonfinancial corporate borrowers, including many that issue loans found in U.S. CLO collateral pools.

At the 2008 distress peak, this figure was 3.2x.

|

Covenants: The covenant-lite share of the market—debt that lacks the financial maintenance tests that could otherwise bring troubled companies to the negotiating table earlier—continues to reach new heights. According to LCD, the cov-lite share of the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index is currently at a record high of 82%, compared to 15% at year-end 2008.

Credit quality

While the average bid price of S&P/LSTA Index loans is higher—it was 76.35 at Tuesday’s close, versus 64.27 at the November 2008 distress peak—credit quality paints a different picture.

Rating breakdown: Some 58% of Index loans have a facility rating of B–, B, or B+, compared to 31% in November 2008. The share of triple-C loans in the S&P/LSTA Index, at 8%, is slightly higher than the 5% in 2008.

Leverage: According to LCD analysis of S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index issuers that file results publicly, average leverage was 5.35x at 4Q19, compared to 5.03x at 4Q18.

Cash flow coverage: with leverage ticking up, the sample’s average cash flow coverage of outstanding loans eroded to 3.09x in 4Q19, from 1.84x in 4Q08.

Looking at issuers with credit metrics at the “outer edge” with a cash flow coverage ratio of less than 1.5x, and leverage in excess of 7x, the percentage of issuers in the sample with leverage more than 7x swelled to 20% in the final quarter last year, up more than four percentage points sequentially, and up nearly six points year over year.

This is unchanged from 4Q08, but up from 14% in 4Q07.

Issuers with cash flow coverage of less than 1.5x increased year-on-year to 23% of the sample, versus 18% in the fourth quarter of 2018.

In 4Q08, 44% of issuers were operating with a cash flow coverage ratio of less than 1.5x.

|

|

Issuer base

Predictably, the industry make-up of the loan market has shifted. Tech companies account for the biggest slice of the Index, currently at 15%, compared to 3% at the end of 2008.

At the November ’08 distress peak, the loan issuer base was dominated by Publishing, at 7.1%, Utilities, at 6.73%, and Automotive, at 6.53% (currently Publishing and Utilities account for 1.24%, and 2.79% of loan outstandings).

Oil & Gas and Retail, two sectors dominating the distress scene in an otherwise benign environment for distressed pickings in recent years, are almost unchanged from 2008, at 3.56%, and 3.6%. Prior to the 2016 uptick in energy-related defaults, Oil & Gas accounted for 4.7% of Index loans.

|

Maturity risk

In the spirit of the ides of March, the deadline for loan issuers to settle their debt has a way to run, though the amount that needs to be refinanced in that time is more than twice that of 2008.

According to LCD, issuers had $119 billion (now less than $100 billion) of leveraged loans set to mature in the three years ending 2022 at the end of 2019, representing just 10% of total outstandings.

At year-end 2008, $45 billion was scheduled to come due in the three year-period between ending 2011, which represented 7.9% of total outstandings.

|

Finally, in terms of defaults, when default rates hit a peak of 10.8% in 2009, the LTM defaulted amount was $63 billion. In today’s market, it would require a default rate of only 5.4% to reach the same amount of defaulted loans.

Moreover, a 10.8% default rate in today’s market would equate to $127 billion of defaulted loans.

|

|

This analysis was written by Rachelle Kakouris, who tracks the leveraged loan/distressed debt markets for LCD.