Campaign groups have called on the Bank of England to put tougher requirements in place to force banks to align with climate accords.

The comments come after the central bank unveiled its climate stress tests and ruled out instituting capital requirements for banks to limit lending to high-carbon projects.

The BoE's Biennial Exploratory Scenario climate stress test, unveiled June 8, will not be used to set capital requirements, but it may affect the BoE's supervisory approach.

ShareAction, which organized shareholder resolutions on fossil fuel funding at HSBC Holdings PLC and Barclays PLC, said the BoE had missed an opportunity with its climate change tests. Wolfgang Kuhn, ShareAction's director of financial sector strategy, said banks are not doing enough to reduce fossil fuel lending. To avoid scrutiny, lenders often point toward their green lending or claim that if they did not lend to fossil fuel producers, another bank would step in.

"The regulator should impose either a green-supporting factor when it comes to capital charges or put in a brown-penalizing factor. It doesn't matter too much whether you penalize the one or help the other, it's about the delta between the two. But regulators are not doing that," Kuhn told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Regulators often claim it is not proven that supporting green financing is less risky than supporting brown financing, said Kuhn.

"I understand in the short term it might be more risky lending to small solar panel company than a big oil company, but as a society we have already established that brown is super-risky and green is not. So regulators just need a long-term focus and financial stability in 30 years is just as important as it is now," he said.

Call for stronger legislation

Greenpeace's senior climate finance advisor, Charlie Kronick, said the BoE's delay in rolling out the climate tests because of the pandemic means the financial system has even less time in assessing its vulnerability to climate change.

He welcomed the BoE's test but said it was inadequate because it did not require banks to align with the Paris Agreement on climate change, which committed countries to keep the rise in global average temperatures to below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

"As the host of the G-7 and this year's pivotal global climate summit, the government and the Bank of England can no longer rely on disclosure of risk. We need legislation that forces all banks and asset managers to align all financing activities with the goals of the Paris Agreement. That would be genuine climate leadership," said Kronick via email.

The BoE's test uses three scenarios of early, late and no additional action to explore two key risks from climate change, assessing the effects over a 30-year horizon.

The first is the transition risk, arising from the structural changes to the economy needed to meet net zero carbon emissions targets. The second is the physical risk, which is the risk associated with higher global temperatures

The BoE's climate stress test does not go far enough, said Simon Youel, head of policy and advocacy at financial reform group Positive Money. While he accepted that banks' funding of high-carbon projects could not be ended immediately, he said they must stop financing new high-carbon energy projects to bring them in line with the IEA's recommendations that no new fossil fuel projects can begin if the world is to hit the target of zero emissions by 2050.

"The Bank of England should introduce harsher capital rules for high-carbon lending. Basel rules already state that 150% or higher risk weight should be applied to reflect the higher risk of some assets. To reflect climate risk, the Bank of England should introduce 150% risk weights for existing fossil fuel exposures, and much higher risk weights for investments relating to the production of new fossil fuels," said Youel.

Alternatively, the BoE could introduce an additional capital buffer for banks engaged in high-carbon activities, he suggested.

Scope Ratings' analysts believe the BoE climate stress test is "likely to impact capital requirements in the future," they said in a note to investors.

'Dirty' financing

Banks are under increasing pressure on climate change. HSBC, for instance, has committed to phasing out financing of coal-fired power and thermal coal mining by 2030 after pressure from a coalition of investors led by ShareAction.

Barclays PLC faced a shareholder rebellion at its annual general meeting in May when 14% of investors supported a proposal that would require the bank to wind down its lending to the fossil fuel sector.

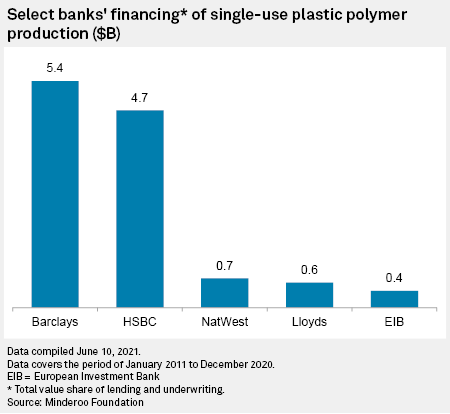

Indeed, Barclays has been named at the biggest provider of financing in the making of single-use plastics in a report from the environmental group The Minderoo Foundation, providing $5.4 billion of financing between 2011-2020, ahead of the next British bank HSBC, which was ranked in fifth place, providing $4.7 billion in financing.

Among the banks assessed by The Minderoo Foundation's report is the European Investment Bank Group, which describes itself as the EU's climate bank and one of the world's financers of climate action. It criticizes the use of single-use plastics on its website.

But, according to the report, the EIB funded single-use plastic manufacturing to the tune of $400 million over the past decade.

The EIB did not dispute the figure but a spokeswoman said via email that "80%" of its lending to the plastics sector went mainly to support research, development and innovation at these companies. It said some of its financing went toward modernizing existing production capacity but mainly to improve energy efficiency.

The bank said it "actively supported projects that contribute to increasing the recycling of plastic waste as well as development of bio-based materials in support of the transition to a circular economy."

Barclays and HSBC declined to comment on the report.

Lloyds said that while it recognizes the inherent sustainability risks in plastics, it will support the sector as it transitions to a lower-carbon environment.

NatWest said the plastics industry will be captured within its commitment to be aligned with the Paris Agreement by 2030 with net-zero emissions by 2050, as part of the Net Zero Banking Alliance of leading banks, and the industry falls within the scope of its commitment to 50% absolute emissions reduction by 2030.