Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

22 Feb, 2023

By Sanne Wass

| The U.K.'s Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation, part of HM Treasury, has grown its staff from 40 full-time employees to more than 100 since Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Source: Mtcurado via Getty Images. |

More aggressive policing of sanctions against Russia is on the cards as EU and U.K. regulators move to strengthen their enforcement powers, putting financial institutions on alert.

|

As the anniversary of Russia's invasion of Ukraine approaches, European authorities' focus is shifting from implementing new sanctions to enforcing existing ones. The European Union is introducing minimum standards for sanctions penalties, while the U.K. has increased staffing at its sanctions body by 150% and granted it greater enforcement powers.

"Clearly, there's an intention and focus on enforcement as a next step beyond the expansion of the scope of sanctions themselves," said Andrea Hamilton, a partner in the corporate group at law firm Milbank.

With big international banks largely well equipped to deal with sanctions, smaller regional banks and non-bank financial actors such as funds may face a higher risk of regulatory action, according to experts.

Unprecedented volumes

The EU and U.K., along with the United States and other nations, have introduced unprecedented sanctions against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine a year ago. The sanctions targeted the country's banks, individuals, businesses and government.

Western financial institutions play a key role in the practical implementation of the sanctions, for example through the blocking of accounts, and are also required to detect and report suspicious activity to authorities. While banks already have screening processes in place, the sheer volume of new sanctions against Russia and the rapid addition of people and entities to sanctions lists have presented new and greater challenges to institutions compared with previous sanctions programs, Doyle said.

Financial institutions have historically been hit with some of the largest fines over sanctions breaches. Authorities globally issued $21.4 billion in sanctions-related penalties to financial institutions from 2009 to 2022, research by Fenergo shows.

U.S. authorities have awarded the heaviest penalties. BNP Paribas SA paid $8.9 billion to U.S. prosecutors in 2015 after pleading guilty to violating sanctions against Sudan, Iran and Cuba. Banks including HSBC Holdings PLC, ING Groep NV, Standard Chartered PLC and Barclays PLC have also paid large sums to U.S. authorities over sanctions breaches.

Financial institutions risk investigations by enforcement agencies into sanctions breaches, and also face scrutiny from regulators over potential failures to meet their financial crime screening and reporting obligations, said John Bedford, a partner at Dechert specializing in white collar investigations.

Netherlands-based ING, one of Europe's largest banks, said it is using its regular robust framework and tooling to keep on top of the changing sanctions regime. "We do expect that in 2023 there will be increasing focus by regulators and enforcement agencies on sanctions implementation," said an ING spokesperson, adding that much of the focus will be on financial institutions.

Enforcement crackdown

European authorities appear to be positioning themselves to crack down more aggressively on breaches than has been the case with previous sanctions regimes.

"We are seeing a paradigm shift

In the EU, changes are underway that will make enforcement more consistent across the bloc. The European Commission in December put forward a proposal to criminalize the violation of EU sanctions against Russia, which will harmonize definitions and introduce minimum penalties across member states.

This may go some way to closing the "enforcement gap" that exists in the EU due to the different authorities, judicial practices and punishments across member states, according to a recent Milbank note. While the European Commission issues EU sanctions, the enforcement responsibility falls on each member state.

The EU has also launched a sanctions whistleblower tool to facilitate the reporting of sanctions violations or circumvention to the Commission.

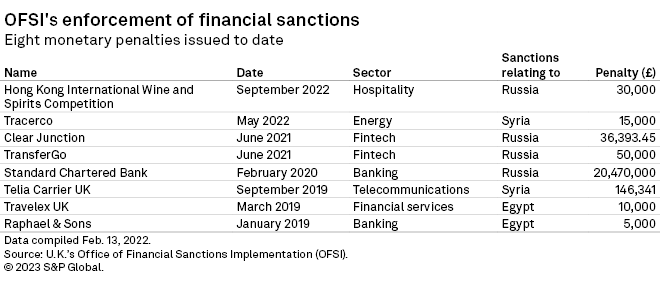

The U.K.'s Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation, or OFSI, has "significantly enhanced its ability to ensure effective enforcement" of financial sanctions against Russia, a spokesperson told S&P Global Market Intelligence by email.

The agency has grown its staff from 40 full-time employees to more than 100, including in its enforcement team, since Russia's invasion of Ukraine in response to increased demand, the spokesperson said. OFSI "is consequently investigating a higher number of complex cases," the spokesperson said.

OFSI received 236 breach reports since the invasion of Ukraine as of June 2022, according to its latest annual review. These will need to be investigated and may result in penalties or public censure, according to the Milbank note.

Changes to OFSI's enforcement powers will also make it easier for the regulator to impose monetary penalties on those breaching sanctions, OFSI said in the annual review. The Economic Crime Act 2022 allows OFSI to levy civil fines without having to prove that a person had knowledge or reasonable cause to suspect that sanctions were violated.

Funds at risk

Even as authorities step up enforcement, it could take years before investigations result in actual penalties, said Doyle of Fenergo. BNP Paribas' 2015 sanctions penalty, for example, related to transactions processed before 2012.

"It is inevitable that there will be a lag between all of the sanctions coming in, those reports being lodged and dealt with, and determining how they are going to deal with that," said Dechert's Bedford.

Compared to other sectors, banks are generally well-equipped to deal with sanctions, and enforcement actions may as such focus their efforts on non-financial entities, said Daniel Tannebaum, global head of sanctions at consulting firm Oliver Wyman. This is especially the case for those banks that dealt with U.S. fines and active supervisory oversight in the past, he said.

"The bigger banks have pretty sophisticated controls in place to deal with this," said Bedford, adding that banks will also benefit from their general efforts to derisk from Russia since the invasion of Ukraine.

Rather, regulators are likely to shift their focus towards other types of financial institutions, said Darshak Dholakia, a partner at Dechert who specializes in economic sanctions.

Non-bank financial actors such as funds may face a higher risk of regulatory action because they generally have less developed sanctions screening infrastructure compared to banks and will also take less time for authorities to investigate, said Mark Padley, of Milbank's litigation and arbitration group.

Smaller regional banks in EU countries with historically close ties with Russia will also be more vulnerable to sanctions breaches and likely face regulatory scrutiny, Doyle said.

This could have a knock-on effect on international financial institutions providing correspondent banking services. If a U.S. bank, for example, helps process dollar transactions for a sanctioned entity through their correspondent banking clients, "that bank has some serious questions to answer to the U.S. regulator," Doyle said.

To learn more about how the war has affected different markets and sectors sign up for a demo of S&P Capital IQ Pro