Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

6 Sep, 2022

By Cathal McElroy and Mohammad Taqi

| The unpopularity of banks among many members of the public could encourage more governments to impose windfall taxes as cost of living pressures increase. Source: Finbarr O'Reilly/Getty Images News via Getty Images |

More European countries could introduce windfall taxes on banks if inflation continues to rise and cost-of-living pressures intensify.

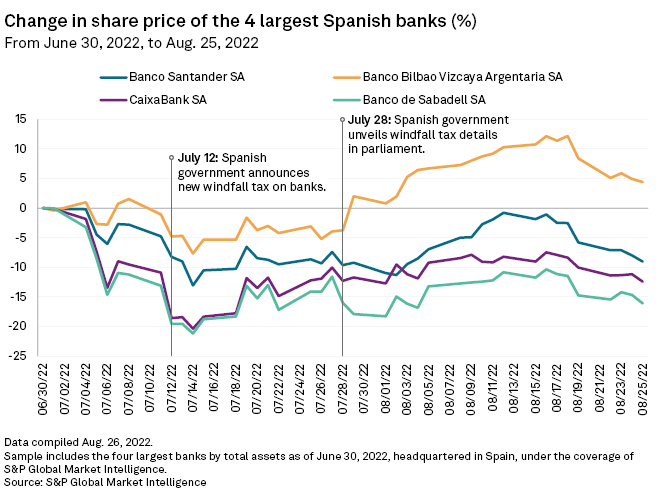

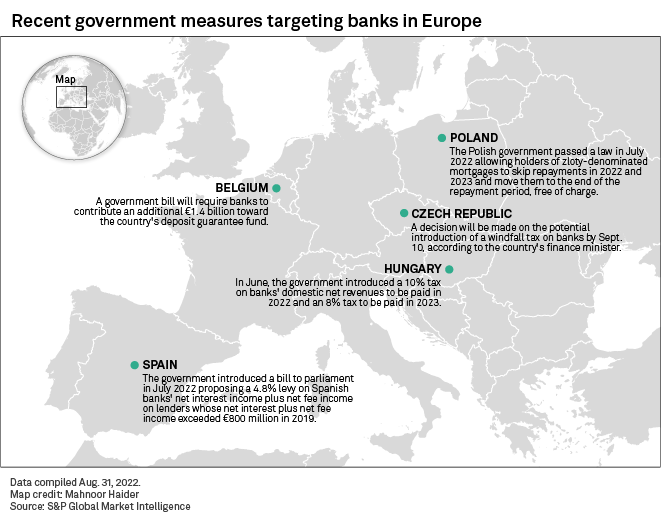

Spain became the biggest European economy so far to target lenders' profits through a windfall tax to help fund its response to the cost of living crisis when it announced a plan in July to raise €3 billion from domestic banks' 2022 and 2023 earnings. Hungary previously announced a new bank tax in May, while the Czech Republic has plans for a similar levy.

The moves come as inflation hits double digits in many countries across the continent, exacerbating cost of living pressures for voters. Many European governments have already imposed windfall taxes on oil and gas companies, whose profits have surged off the back of runaway energy prices fueled by shortages caused by the war in Ukraine.

Banks are likely to become another target if the crisis deepens through the winter, particularly in countries with high debt-to-GDP ratios, such as Greece and Italy, analysts and economists said.

"Spain imposing this tax definitely raises the prospect of other countries doing the same," Johann Scholtz, bank credit analyst at Dutch asset management company Actiam, said in an interview. "Banks are a bit of a soft target. They are not popular in any section of the population, so it's an easy way to appease people."

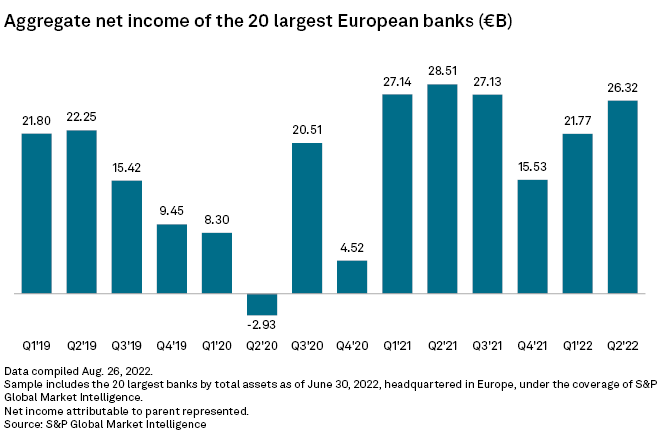

Governments are considering windfall taxes on banks as lenders continue their recovery from the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic. The European banking sector recorded another strong quarter in the three months to the end of June, with many of the region's largest lenders beating analysts' estimates for revenues and profits despite a deteriorating outlook for the global economy.

Revenue prospects for banks are also improving as interest rates rise, allowing lenders to increase the margin between what they pay for deposits and what they earn from interest on loans.

Governments could be tempted to take more of banks' profits once lenders begin to see the benefit of rising interest rates in their earnings, said Daniel Lacalle, chief economist at Spanish asset manager Tressis Gestion. "The financial sector has been extremely prudent in passing higher cost to consumers," said Lacalle. "However, if governments start to see mortgage rates rising, they are very likely to consider taxing these profits."

Another justification for taxing eurozone banks further could come from additional profits the lenders are set to make from borrowing ultra-cheap European Central Bank funds, loaned to banks at negative interest rates, that were intended to stimulate lending to the real economy. While much of the ECB's targeted long-term refinancing operation III's, or TLTRO III's, €2.2 trillion found its way to households and businesses, eurozone banks have kept a substantial portion on deposit at the ECB.

The banks could earn between €4 billion and €24 billion in additional revenue from the deposits until TLTRO III comes to an end in December 2024, when the funds must be repaid, according to a June report by Morgan Stanley.

"That can potentially become a politically challenging issue, also seen in conjunction with the support the banks received during the pandemic," said Scholtz.

Inflationary effects

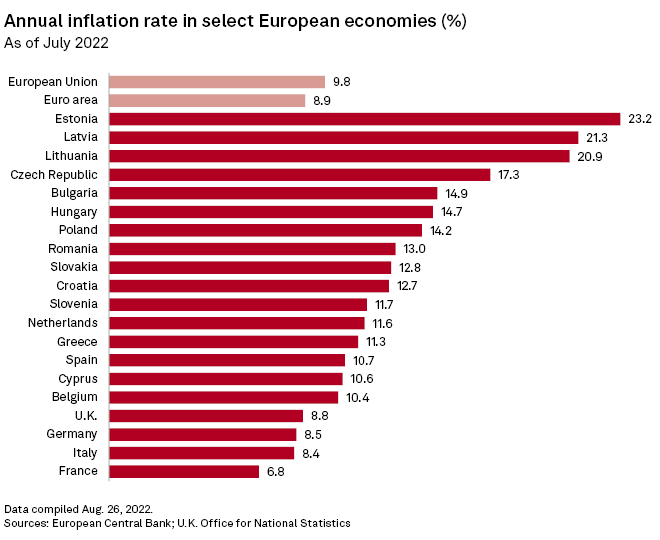

The Spanish government's announcement of a bank windfall tax came as inflation in the country hit 10.7% year over year in July, among the highest in the eurozone, according to the EU's statistical office, Eurostat. The euro area as a whole saw inflation of 8.9% year over year in July. Three countries — Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania — recorded inflation of more than 20% year over year in the month.

The sharp rise in prices is forcing governments to consider various ways of offsetting the impact on the public, particularly those on low incomes, said Jessica Hinds, Europe economist at consultancy Capital Economics. "All governments will be interested in exploring all sources of revenue-raising measures," said Hinds.

Hungary in May was the first European country to hit banks with a new tax when it announced a windfall levy designed to raise 250 billion forints — equivalent to around a third of the Hungarian banking sector's net profit last year — in both 2022 and 2023. Meanwhile, The Czech finance minister has said that a decision on the introduction of a bank windfall tax on the country's lenders will be made by Sept. 10.

Both Hungary and the Czech Republic are experiencing inflation that is among the highest in Europe. Hungary's consumer price inflation rose 14.7% in June, while the Czech Republic's increased 17.3%, Eurostat data shows. To tackle prices, the central banks of both countries hiked interest rates much more sharply and much earlier than the European Central Bank, which has provided a significant boost to banks' income.

The ECB, which is responsible for maintaining financial stability in the eurozone, of which Spain is a part, has previously discouraged the introduction of additional taxes on banks. In response to a proposal by the Lithuanian government to increase taxes on lenders, a December 2019 statement by the ECB said the measure "would be undesirable to the extent that such taxes would place undue burden on banks, hampering the provision of credit with a knock-on effect on growth in the real economy."

Contagion

Concern about the potential spread of bank windfall taxes across Europe was evident during European lenders' second-quarter earnings calls with analysts and investors. The impact of windfall taxes or the prospect of their introduction in other jurisdictions was discussed during eight out of 20 calls involving the eurozone's largest banks by total assets, an analysis by Market Intelligence shows.

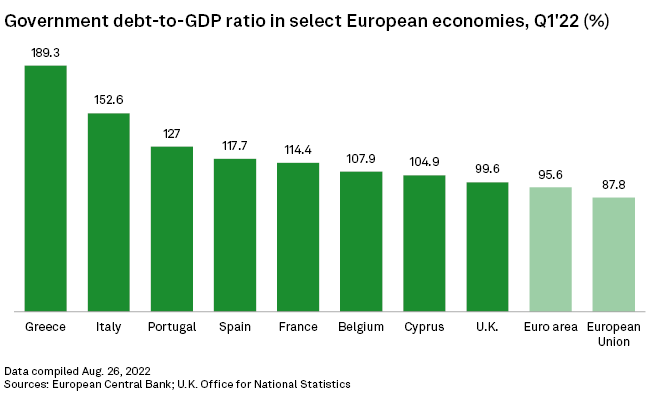

Countries with large debt-to-GDP ratios could be the most likely to consider measures such as windfall taxes due to their reluctance to increase borrowing further, said Hinds.

"The countries with the worst debt dynamics and the ones that are feeling the pinch more from the cost of living crisis will be the ones that will want to, and need to, explore as many options to raise revenues compared to their peers," Hinds said.

Greece and Italy had the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the EU at the end of March by some distance, at 189.3% and 152.6%, respectively. Five of the other 26 EU countries had debt-to-GDP ratios of above 100%, including France and Spain. The EU's total debt-to-GDP ratio was 87.8% at the end of March, while the U.K., which is no longer in the EU, had a ratio of 99.6%.

Italy presents the most obvious risk of another government introducing a bank windfall tax, Gonzalo López, bank analyst at independent equity broker Redburn, said in an interview. "They are going to have elections [in September] and when you look at the polls, it seems that the leading parties right now could be the ones that could introduce something similar," said López.

Italy is due to elect a new government Sept. 25 following the collapse of its coalition government in July. The far-right populist Brothers of Italy led a poll of polls by Politico as of Aug. 31 on 24%, with center-left Democratic Party on 23%.

Tax burden

Europe's banks already face a variety of levies on their income.

Twelve of 26 European countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development imposed financial stability contributions on banks as of March 2021, according to data from independent U.S. tax policy nonprofit Tax Foundation. Lenders also have had to make regular contributions since 2016 to the European Central Bank's Single Resolution Fund, which stood at €52 billion as of July 2021. The fund is designed to rescue failing banks and avoid a taxpayer bailout like that which followed the global financial crisis.

Meanwhile, Belgium is asking its banks to contribute an additional €1.4 billion toward the country's deposit guarantee fund following a surge in deposits during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Taxes are not the only approach governments are taking to ease pressure on increasingly squeezed voters. Poland passed a law in July that allows holders of zloty-denominated mortgages to skip repayments in 2022 and 2023 and move them to the end of the repayment period, free of charge. Lenders in Poland face costs roughly equivalent to the sector's total profits for the first five months of 2022, Market Intelligence data shows.

Pressure on governments to find new sources of revenue is likely to mount unless prices, particularly for energy, begin to fall. "We really need energy prices to come down if we are to see an improvement in the cost of living and real disposable income starting to rise," said Hinds.

If cost pressures intensify, more European banks should prepare to face higher tax bills, Lacalle said.

"It's very possible that we see these kinds of taxes in other major European economies," said Lacalle. "Right now, in numerous European countries, they see the financial sector as the solution to, not the cause of, this crisis."