Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Jun 03, 2019

UK Manufacturing moves into decline as boost from Brexit stockpiling fades

- Manufacturing PMI falls below 50.0 to second-lowest level in over six years

- Order books and employment both fall

- Price pressures at multi-year low

UK manufacturers reported a deterioration of business conditions in May amid one of the steepest downturns in order books seen over the past six years. The turnaround from strong growth earlier in the year was partly due to an unwinding of Brexit-related stockpiling, though also reflected weaker underlying demand. While falling orders and high inventories point to further downward pressure on production in coming months, future expectations improved to provide a welcome upbeat assessment of longer-term prospects.

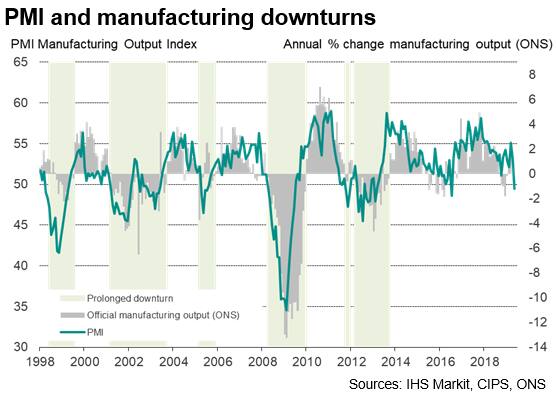

PMI in contraction territory

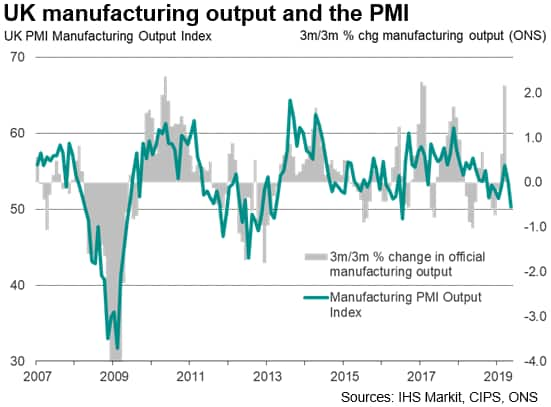

The IHS Markit/CIPS Manufacturing PMI fell from 53.1 in April to 49.4 in May, dropping below the 50.0 'no change' level for the first time since July 2016. There have only been two occasions in the past six years that the PMI has fallen below 50. While the slide into contraction territory in the month immediately following the Brexit vote in 2016 proved short-lived in terms of both PMI and official manufacturing data, with confidence having been quickly restored after central bank action and swift political change, all other occasions in which the PMI has fallen below 50 have been marked by prolonged downturns in production, as measured by the Office for National Statistics.

The survey's output index fell 3.3 points in May, down to its lowest reading since July 2016 and the second-lowest figure since March 2013.

At a level indicative of manufacturing production falling at a quarterly rate of approximately 0.4%, the PMI survey output index suggests the goods-producing sector will act as a drag on the economy in the second quarter. Such a drag marks a stark contrast to the strong boost seen in the first quarter, with anecdotal evidence from manufacturers indicating that the impact of pre-Brexit stockpiling in the first quarter (ahead of a feared no-deal Brexit on 31st March) has moved into reverse in the second quarter.

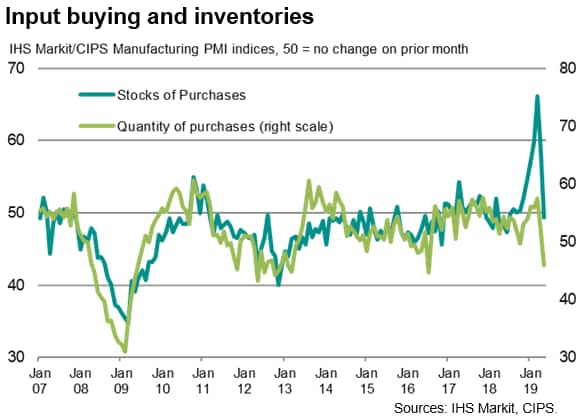

Stockpiling impact wanes

Such a change in stock building is evidenced by manufacturers' inventories of inputs falling in May for the first time since July 2018, contrasting with record stock accumulation earlier this year. Similarly, the amount of inputs bought by manufacturers fell in May to the greatest extent since July 2016, in contrast to the surge in buying seen earlier in the year.

Steep drop in demand

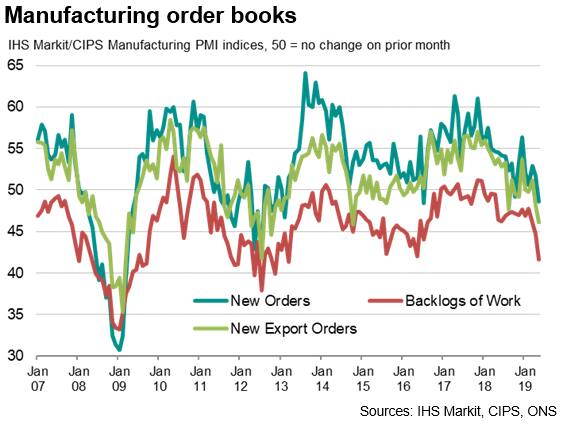

Order book data add to concerns about the health of the manufacturing sector, with new orders dropping in May to the second-greatest extent since February 2013. Only July 2016 saw a marginally steeper decline. New export orders fell for a second month, dropping at the fastest rate since October 2014.

The deteriorating inflow of new business meant companies increasingly ate into previously placed orders to support production, leading to the largest drop in backlogs of work since March 2013.

Consumer boost

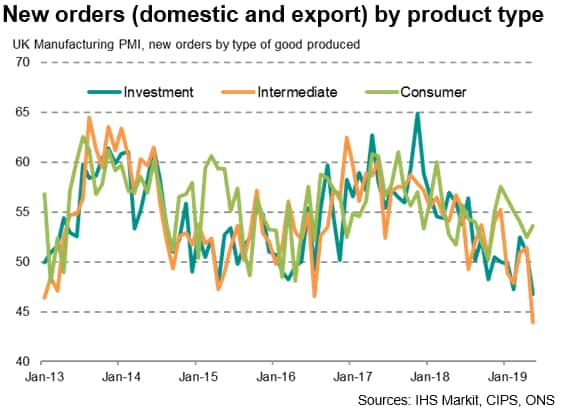

Looking further into order book trends, demand for consumer goods continued to hold up reasonably well, but orders for investment goods (such as business equipment and machinery) and intermediate goods (manufactured goods supplied as inputs to other producers) both fell sharply. The drop in demand for investment goods was the steepest since November 2012. The fall in orders for intermediate goods was the sharpest since July 2012.

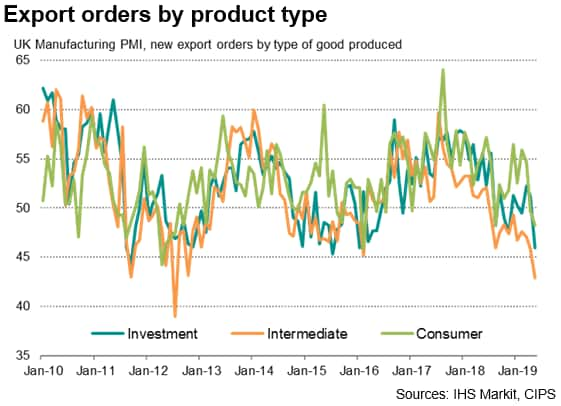

Exports meanwhile fell for all three categories of product, though the decline was especially steep for intermediate goods, blamed by some manufacturers on EU customers switching suppliers from the UK to EU-based firms.

Forward-looking indicators

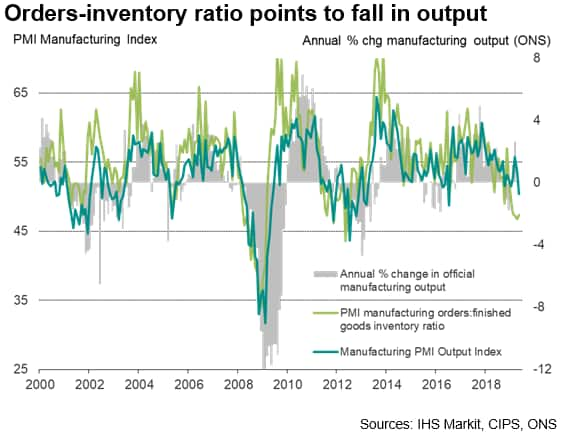

Forward-looking indicators sent mixed signals. The new orders to inventory ratio rose slightly but remained at one of the lowest levels seen since the global financial crisis. The recent decline in the ratio had forewarned of the short-lived nature of the upturn in production earlier in the year and the subsequent drop into decline in May. The ongoing low ratio points to further downward pressure on production in coming months due to the combination of falling inflows of new business and rising inventory levels.

More encouragingly, the sole sentiment-based question in the PMI survey, which asks about firms' expectations for their own production over the coming year, edged higher in May to its most pronounced since last September, suggesting that firms have become slightly more optimistic that growth will resume at some point over the next 12 months.

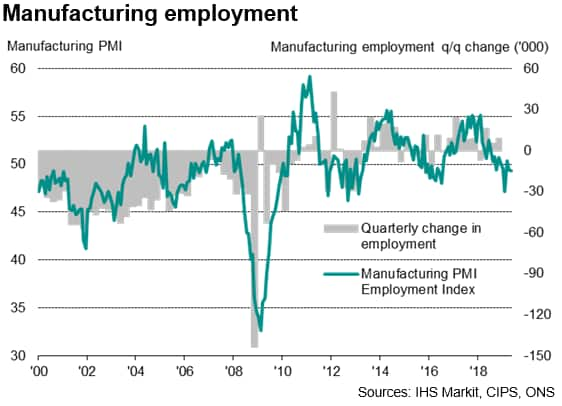

Job losses

Meanwhile, manufacturers cut their headcounts in the face of tough trading conditions, with employment falling in May (albeit only modestly) for the fourth time in the past five months.

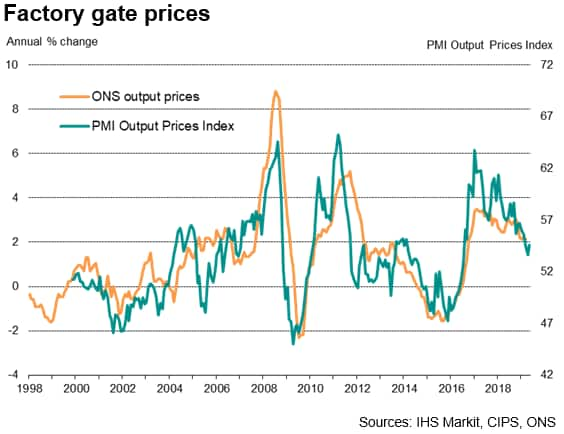

Price pressures at multi-year lows

Price pressures remained among the softest for several years. The pace of input price inflation eased to the second-slowest recorded over the past three years, often reflecting weakened pricing power among suppliers amid subdued demand for inputs. Average supplier delivery times - a key gauge of supply chain price pressures - shortened for the first time since September 2015, highlighting a general shift towards a buyers' market.

Average prices charged by manufacturers for their goods meanwhile rose at a slightly faster rate than seen in April, but the increase was nevertheless the third-slowest recorded for just under three years and well below the average rate of increase seen throughout last year. The survey data are broadly indicative of manufacturing prices rising at an annual rate of just under 2%.

Methodological note

The main PMI indices are based on companies reporting whether key metrics such as production volumes, new order inflows, employment or prices have risen, fallen or stayed the same at mid-month compared to the prior month. Being derived from objective metrics rather than sentiment, the PMI indicators provide an accurate guide to official manufacturing data. The PMI also tends to outperform other surveys which are based on subjective measures such as whether production is above or below 'normal', or whether order books are 'satisfactory', not least because the definition of such subjective measures can change over time - as appears to have occurred since the global financial crisis. Read more in our special paper.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS

Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2019, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-mfg-moves-into-decline-as-boost-from-brexit-stockpiling-fades-190603.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-mfg-moves-into-decline-as-boost-from-brexit-stockpiling-fades-190603.html&text=UK+Manufacturing+moves+into+decline+as+boost+from+Brexit+stockpiling+fades+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-mfg-moves-into-decline-as-boost-from-brexit-stockpiling-fades-190603.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=UK Manufacturing moves into decline as boost from Brexit stockpiling fades | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-mfg-moves-into-decline-as-boost-from-brexit-stockpiling-fades-190603.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=UK+Manufacturing+moves+into+decline+as+boost+from+Brexit+stockpiling+fades+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-mfg-moves-into-decline-as-boost-from-brexit-stockpiling-fades-190603.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}