Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Jun 11, 2019

UK job market tight but showing further signs of cooling

- Unemployment rate at lowest since 1974 and employment at record high

- But job vacancies fall for fourth month running, employee numbers fall

- Wage growth looks to have peaked

The official UK labour market data again delivered encouraging headlines, but once again the details took the shine off some of the top-line numbers and add to the case for interest rates to be on hold for some time to come.

Wages rise amid tight labour market

The labour market clearly remains tight, with the unemployment rate holding at 3.8% in the three months to April, its lowest since 1974. The number of job vacancies per unemployed person was meanwhile running at 1.56 in April, its lowest since records began in 2001 with the exception of the 1.54 ratio seen in March. To help put this in some perspective, the long-run average for this ratio is 3.17.

The tightness of the job market continued to push up wages. Regular pay (excluding bonuses) rose 3.4% on a year ago in the three months to April, up from 3.3% in the three months to March.

A new record was meanwhile seen for employment, which rose by 32,000 in the three months to April, pushing the total number of people employed up to a new high of 32.75 million.

Cooling demand for staff

The warning lights are hidden in the detail of these headline numbers.

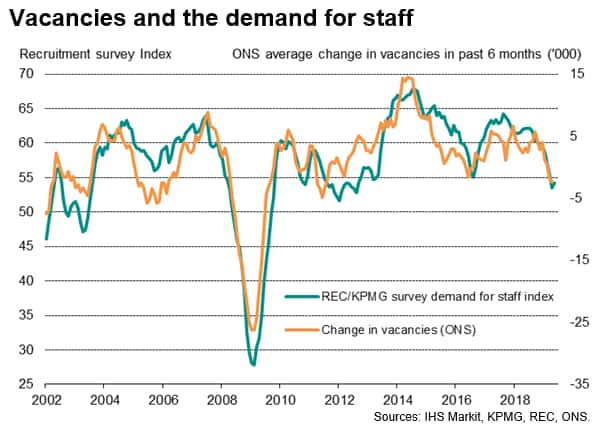

Frist, in terms of vacancies, which provide a good indication of changing demand for staff at employers, the total number of open positions has in fact now fallen in each of the past four months, albeit still high at 837,000 in April. The downturn in vacancies matches the recruitment industry survey data, which has likewise registered cooling growth in the demand for staff from employers in recent months. This series in fact peaked last summer and has been running at its lowest since mid-2012 in April and May.

Recruiters have reported that companies have become wary of taking on extra staff in the current uncertain business environment, often linked to Brexit, curbing the number of vacancies.

Falling employee numbers

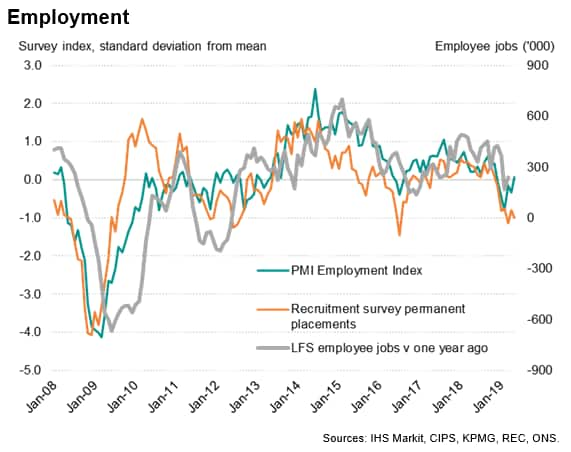

Another warning light comes in the form of a 32,000 drop in employee numbers in the three months to April, according to the Labour Force Survey (LFS), which represents the biggest fall for five years. While this series is volatile, the growth trend has clearly moderated in recent months; a slowdown which tallies with the survey data. Both the PMI's employment index and the recruitment industry survey data have indicated slower jobs growth in recent months, and both have a good track record of anticipating changing employee levels.

The recruitment industry survey series, which looks at the number of people placed in permanent jobs each month, is a particular concern as it tends to change earlier than the PMI and LFS series, and is currently by far the weakest of the three.

The worsening employee trend contrasted with a rise in self-employment (which pushed the headline employment number to its new record), but hints at companies being increasingly reluctant to commit to taking on permanent staff.

Has wage growth peaked?

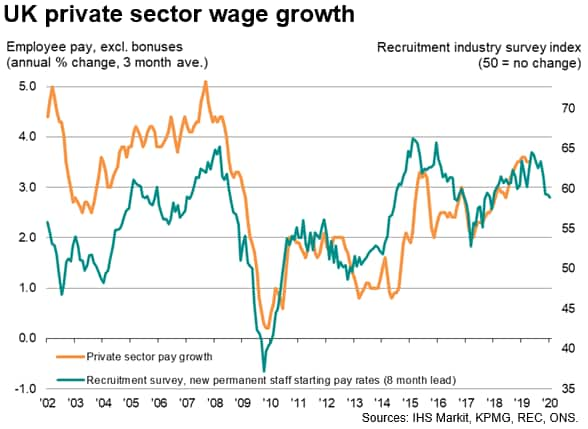

Finally, there are signs that wage growth may have peaked, notably in the private sector. Regular pay growth for private sector workers rose 3.5% in the three months to April, but that's down from 3.6% in the three months to February. Small changes such as this are by no means indications of a turning point, but when looked at alongside the survey data, the likelihood is that pay pressures have started to ease.

Looking again at the recruitment industry survey data relating to pay offered to people starting new permanent jobs - which acts as a good leading indicator of wider earning trends - pay growth has eased markedly in recent months since topping-out back in September of last year. The rate of increase signalled for May was the slowest for just over two years.

To clarify, the survey data continue to indicate rising pay, but hint that the annual rate of increase is likely to drop below 3% in coming months.

Policy on hold

The labour market data form an important part of the monetary policy decision at the Bank of England, and the resilience of the jobs market and pay growth have been instrumental to calls for higher interest rates. Policy has been on hold, however, due to the heightened uncertainty facing the UK economy emanating from Brexit. In that respect, the current tightness of the labour market suggests that it might not take much in the way of positive news to rekindle hiring and push wage growth higher again. However, Brexit is only part of the reasons for the slowdown in hiring, as the UK is also struggling against a headwind of slower global economic growth , potentially limiting any upside even in the event of a smooth Brexit.

In this environment, the Monetary Policy Committee looks likely to keep policy on hold for some time to come. IHS Markit's forecasting team is not anticipating the first UK rate rise until May 2021.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS

Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2019, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-job-market-tight-but-showing-further-signs-of-cooling-190611.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-job-market-tight-but-showing-further-signs-of-cooling-190611.html&text=UK+job+market+tight+but+showing+further+signs+of+cooling+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-job-market-tight-but-showing-further-signs-of-cooling-190611.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=UK job market tight but showing further signs of cooling | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-job-market-tight-but-showing-further-signs-of-cooling-190611.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=UK+job+market+tight+but+showing+further+signs+of+cooling+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-job-market-tight-but-showing-further-signs-of-cooling-190611.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}