Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Mar 05, 2018

UK PMI surveys show economy regaining momentum, price pressures cool

- Service sector upturn helps economy regain momentum in February

- 'All sector’ PMI at 54.2, signals GDP growth approaching 0.4% in Q1

- Output price inflation cools further to six-month low

The UK economy picked up steam again in February after a slow start to the year, according to the PMI surveys, led by faster growth in the service sector. Improved trends in business activity and new orders encouraged firms to take on staff in increased numbers, though signs of capacity constraints continued to be seen across the economy. Selling price inflation meanwhile cooled to a six-month low amid slower growth of input costs.

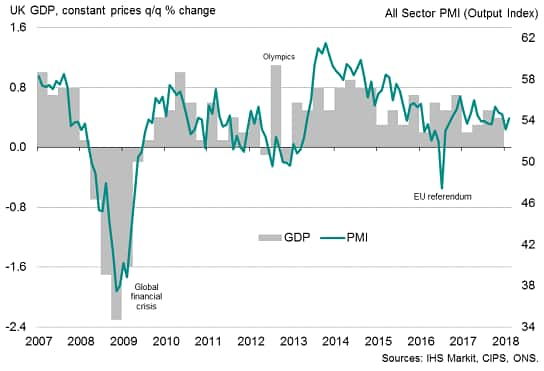

Steady first quarter growth

The ‘all-sector’ IHS Markit/CIPS PMI Output Index rose from 53.1 in January, its lowest since August 2016, to 54.2 in February. While the PMI remains below the average seen last year, the readings for the first quarter so far signal a solid GDP growth rate of just under 0.4%.

UK PMI and GDP compared

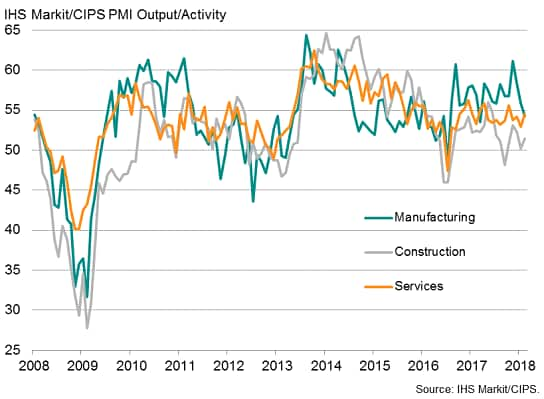

Output rose across all three major business sectors of the economy in February, albeit with substantial variations in trends. Service sector business activity rose at the steepest rate for four months, buoyed by the largest inflow of new work seen over the past nine months. The upturn meant services took over from manufacturing as the fastest growing sector of the economy for the first time since March of last year, albeit by a small margin.

UK PMI output index for the three main sectors

Within services, by far the strongest expansion in recent months has been recorded in the financial services sector, while the weakest performance has been seen in hotels, restaurants and catering, followed by computing and IT services. These lagging sectors have reported signs of customer spending having been hit by rising prices and intensifying business uncertainty.

The goods-producing sector saw output rise at the weakest rate for nearly a year, though new orders picked up, suggesting at least some of the slowdown in activity could be temporary, linked in part to capacity constraints in supply chains. Widespread supplier delivery delays were again reported.

Output growth meanwhile picked up in the struggling construction sector from the stagnation seen in January, though remained very modest. Inflows of new building work fell for a second month, suggesting the malaise could extend into March. A renewed decline in civil engineering output was accompanied by weak house building growth, though commercial activity showed the largest rise since last May.

Job creation buoyed by optimism

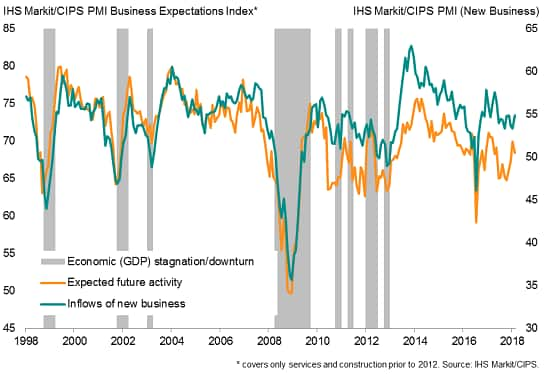

Measured across all three sectors, new orders rose at the joint-fastest rate for nine months, with backlogs of work also increasing as many firms struggled to cope with demand. Job creation consequently accelerated to a six-month high as companies raised capacity, improving in all three sectors.

New orders and business expectations

Companies’ expectations about their business activity in a year’s time meanwhile eased from January’s ten-month high as Brexit uncertainty continued to be widely reported, but remained the second-highest seen over the past nine months to suggest that businesses optimism remains generally upbeat.

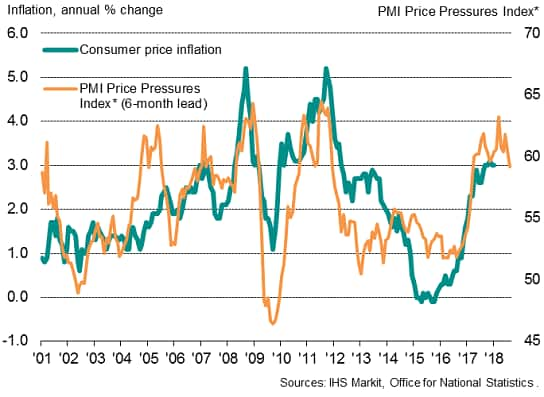

Inflationary pressures cool

Price pressures cooled again, suggesting inflationary pressures peaked back in October, though remained stubbornly high. Average input costs rose at the weakest rate for 17 months, the pace of increase remaining elevated but well below the peaks seen early last year. Only construction companies reported faster growth of costs, often linked to supply shortages. Manufacturing input cost inflation eased markedly but remained especially high, linked to higher fuel and energy prices alongside general supplier price hikes. Service sector cost inflation meanwhile slowed to a one-and-a-half year low, though continued to be pushed up by supplier price hikes, energy costs and faster wage growth.

UK PMI prices charged and inflation

Average prices charged for goods and services also rose at a marked pace again in February as firms sought to protect margins. The increase was nonetheless the smallest for six months.

Policy dilemma

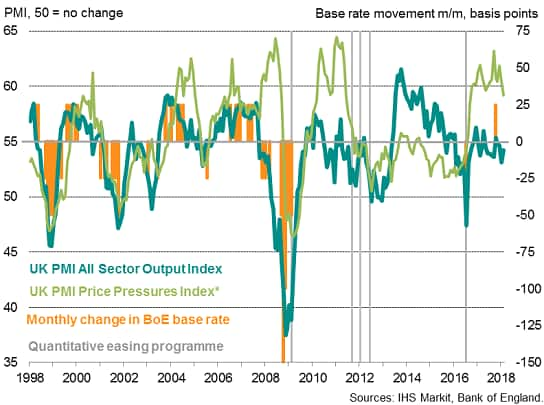

The latest PMI numbers come at a time when policymakers have sounded increasingly hawkish in terms of the need to hike interest rates. Expectations have consequently risen that the Bank of England could hike its policy rate to 0.75% in May, when it next publishes its updated growth and inflation projections. Despite the cooling in price indices signalled by the latest PMI survey, inflationary pressures remain elevated. Further signs of accompanying higher wage growth have also been seen, notably in recruitment industry surveys, adding to the case for rates to rise again.

On the other hand, the argument for higher rates is by no means clear cut. Despite the rise in February, the all-sector PMI output index remains in dovish-to-neutral territory as far as its relationship with historical Bank of England monetary policy decisions is concerned. As such, the output data would normally cast doubts on any imminent rise in interest rates. On the other hand, recent months have seen a break from tradition: since 1999, interest rates have only been raised when the all-sector PMI has been above 56.5, with the sole exception of last November’s hike to 0.5%, when the latest PMI reading had been 55.3.

UK PMI and monetary policy

* The price pressures gauge is a composite index derived from survey measures of input costs and suppliers’ delivery times, the latter being a useful proxy for capacity constraints.

The Bank therefore seems keen to normalise interest rates even if output growth is below levels it would normally like to see when tightening policy. With Bank policymakers sounding hawkish even following the January fall in the PMI to a one-and-a-half year low, the February upturn surely leaves a May rate hike very much in play.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-surveys-economy-regaining-momentum-price-pressures.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-surveys-economy-regaining-momentum-price-pressures.html&text=UK+PMI+surveys+show+economy+regaining+momentum%2c+price+pressures+cool","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-surveys-economy-regaining-momentum-price-pressures.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=UK PMI surveys show economy regaining momentum, price pressures cool&body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-surveys-economy-regaining-momentum-price-pressures.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=UK+PMI+surveys+show+economy+regaining+momentum%2c+price+pressures+cool http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-surveys-economy-regaining-momentum-price-pressures.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}