Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Aug 01, 2019

Accelerating global manufacturing downturn spreads to more countries in July

- Global PMI lowest since October 2012 as 19 out of 30 countries report manufacturing downturns

- Global exports fall at increased rate

- Prices fail to rise for first time in three years

- Job cuts accelerate to seven-year high

PMI surveys indicated that the global manufacturing downturn deepened in July, causing greater job losses and reducing pricing power, as the downturn widened to encompass more countries.

Deepening rate of decline

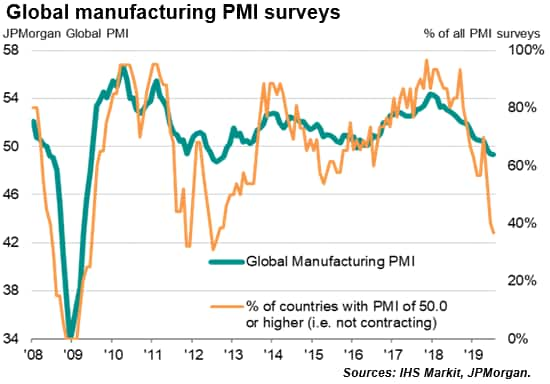

The headline JPMorgan Global Manufacturing PMI, compiled by IHS Markit, fell from 49.4 in June to 49.3 in July, its lowest since October 2012 and indicating a third successive month of deteriorating business conditions.

The number of countries now in decline has increased to 19 out of 30 covered by IHS Markit's manufacturing PMIs which, at 63%, is the highest proportion since August 2012.

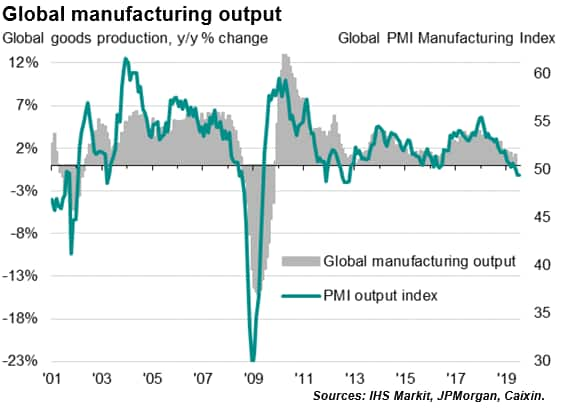

The national surveys collectively indicated that worldwide factory production fell at a rate unchanged on June, dropping for a second successive month in response to the fourth decline in new orders seen over the past five months. The downturn was fuelled by an increased rate of deterioration of worldwide trade flows, with global exports falling to an eleventh consecutive month in July. The latest export decline was the largest since October 2012.

Historical comparisons with official data suggest that the latest drop in the PMI's output index is commensurate with global factory output contracting at an annual rate of just over 1%.

While the rates of decline in output, new orders and exports remained relatively modest compared to that seen ten years ago during height of the global financial crisis, the only other time that the survey has recorded a steeper global manufacturing downturn has been the Asian financial crisis of 1998-1999, the dot-com bubble bursting in 2000-2001 and the European sovereign debt crisis of 2012.

Downturn spreads

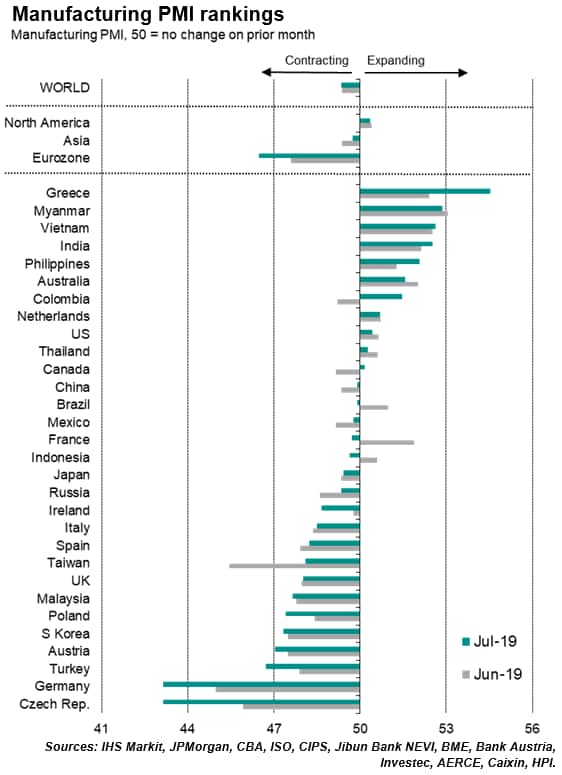

The broadening out of the manufacturing malaise was highlighted by almost two-thirds of all surveyed countries reporting a deterioration of manufacturing conditions in July. The countries in decline now include notable names such as China, Japan, Germany, the UK, Spain, Italy, Brazil, Russia, Taiwan, South Korea and Mexico.

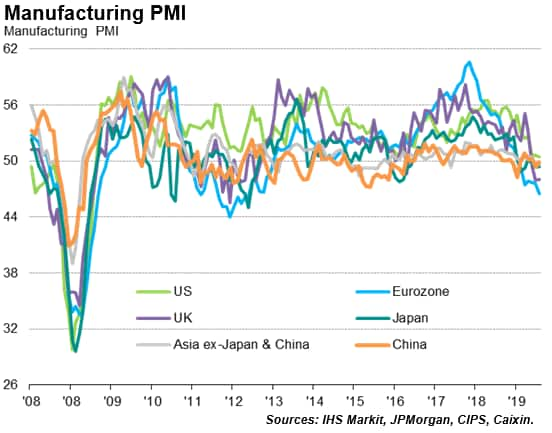

Looking at the world's largest economies, the eurozone as a whole reported the steepest decline (led by intensifying weakness in Germany) followed by the UK and then Japan. A marginal decline was seen in China while business conditions more or less stagnated in both the US and Canada, with the US PMI down to its lowest since 20091.

Trade war winners and losers

Topping the list of manufacturers' reasons for lost orders and reduced output was trade war tensions, notably between the US and China, followed by geopolitical uncertainty which is often itself linked to trade wars. Other companies merely attributed the downturn to a peaking of economic growth.

Some countries nevertheless continue to buck the global slowdown trend. Greece led the manufacturing rankings in July, albeit building from a low base after production slumped in the decade after the global financial crisis, followed by Myanmar, Vietnam, India and the Philippines. The relative success of some of these Asian manufacturing economies appears to be at least in part attributable to trade diversion arising from the US-China spat.

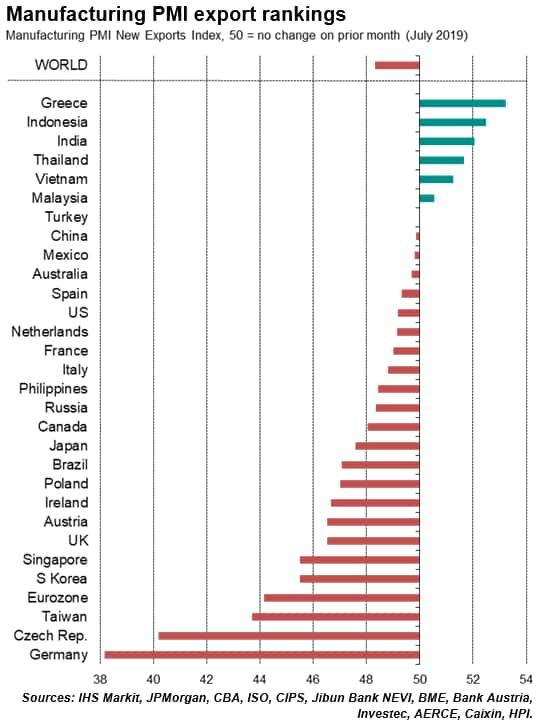

Looking at export performance in July, only six of the 28 countries for which trade data are available reported a rise in exports. These included Indonesia, India, Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia. The only non-Asia country reporting higher exports was Greece.

However, other Asian countries saw steep falls in exports, notably Taiwan, South Korea and Singapore, in part reflecting the dominance of electronics in these countries, a sector which has seen output and orders fall especially sharply in recent months (the global electronics PMI fell to its lowest since 2012 in June). The steepest drop in exports was seen in Germany, followed by the Czech Republic.

Job cuts accelerate to seven-year high

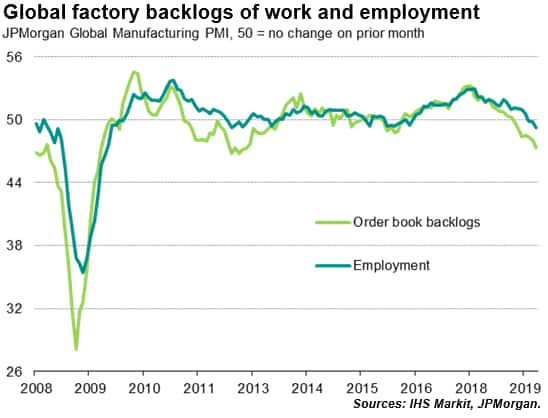

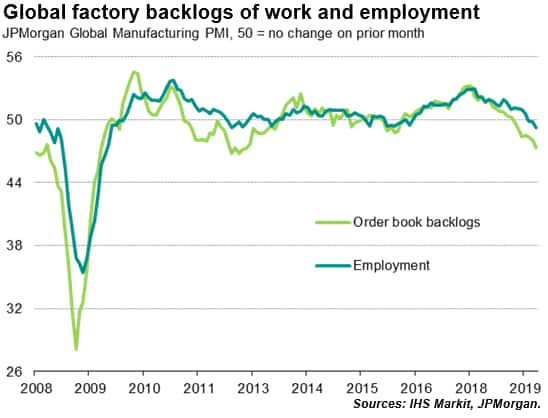

The further deterioration in new order inflows meant firms increasingly relied on previously placed orders to support production. Backlogs of work consequently fell at the fastest rate since November 2012, dropping for a seventh straight month.

Such a sustained decline in backlogs of work typically indicates the development of spare capacity, which commonly results in job losses as companies adjust production volumes lower to meet the reduced demand. Such a situation was indeed seen in July, with the global PMI indicating a third successive monthly decline in factory employment, which fell at the steepest rate for seven years.

Notable economies reporting a decline in employment included the US, China, the eurozone and the UK.

Prices fail to rise for first time in three years

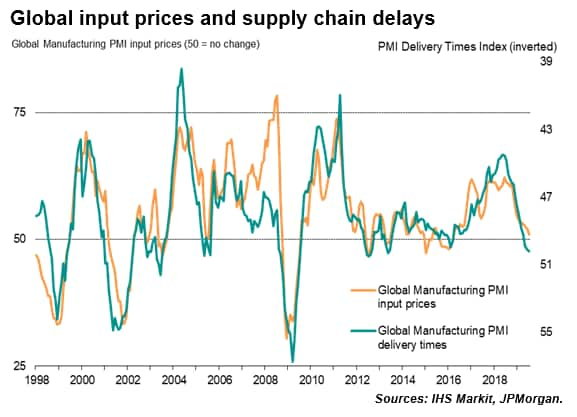

The development of spare capacity was also indicated by a further shortening of average supplier lead-times. Although only marginal over the past two months, recent months have seen the first shift to faster deliveries for the first time in six years as suppliers faced weaker demand. The amount of inputs bought by manufacturers worldwide fell in July at the sharpest rate since September 2012.

The drop in demand for inputs also meant suppliers increasingly offered discounts to shift unsold stock, meaning average input costs rose globally at the slowest rate since prices began rising in April 2016.

Average selling prices at the factory gate meanwhile failed to rise for the first time since August 2016 as manufacturers likewise increasingly competed on price. Prices fell in China, Japan and across the rest of Asia as a whole, as well as in the Eurozone. UK prices rose at the slowest rate for three years. In contrast, selling prices rose at an increased rate in the US, rising to a greater extent than any other country surveyed in July.

1It should be noted that even the near-50 PMI reading seen in the US in fact translates into a contraction in the official measure of manufacturing output (see ourrecent US research noteand a recent analysis onwhat a PMI of 50 means for different countries).

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS

Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2019, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faccelerating-global-manufacturing-downturn-spreads-to-more-countries-in-july-010819.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faccelerating-global-manufacturing-downturn-spreads-to-more-countries-in-july-010819.html&text=Accelerating+global+manufacturing+downturn+spreads+to+more+countries+in+July+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faccelerating-global-manufacturing-downturn-spreads-to-more-countries-in-july-010819.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Accelerating global manufacturing downturn spreads to more countries in July | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faccelerating-global-manufacturing-downturn-spreads-to-more-countries-in-july-010819.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Accelerating+global+manufacturing+downturn+spreads+to+more+countries+in+July+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2faccelerating-global-manufacturing-downturn-spreads-to-more-countries-in-july-010819.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}