Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 19, 2015

Dear Michael Lewis

I would like to issue a public challenge to Mr. Lewis…

In response to yet another round of half-truths and innuendos spoken by Michael Lewis, Bart Chilton, former commissioner of the CFTC and current spokesperson for the Modern Markets Alliance, called Mr. Lewis's claims "A big lie". While I agree that Mr. Lewis, in both "Flash Boys" and his recent piece in Vanity Fair, fabricates claims about how retail investors are mistreated, Mr. Chilton is only half-right. He is correct that execution quality for individual investors is as good as it has ever been. Unfortunately, he does not address some of the other claims made about the equity market. Sadly, there are conflicts of interest in trading on behalf of institutional investors and those trading practices are still relatively opaque.

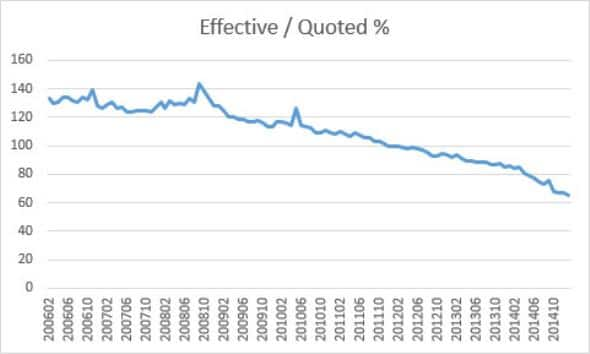

First - let's examine what Mr. Chilton gets correct. While SEC Rule 605 is certainly in need of an overhaul, it has clearly provided massive benefits to retail investors. Statistics show that retail investors who demand liquidity from the market (using market or marketable limit orders) have NEVER had it better. The top retail brokerage firms use the disclosures required by Rule 605 and related metrics adopted by the industry to promote fierce competition among wholesale market makers. The result has been incredible; retail investors received over $600 million in direct price improvement from wholesalers in 2014 alone, up from roughly $100 million in 2004. The superior treatment of retail orders was confirmed in a recent article written in Barrons by award winning journalist William Alpert. While it has received its share of criticism by a cadre of uninformed critics, Mr. Alpert thoroughly researched this article and developed his own statistical programs to analyze actual execution data. They are available via Open Source on GitHub for anyone that wants to improve them, criticize them or simply use them. In particular, his analysis proves that price improvement per share has increased substantially and is certainly not "de minimus" as the critics claim. The following chart shows the benefit to retail investors directly. It shows the trend of the most used metric of execution quality, effective spread divided by quoted spread for a cross section of retail investors since 2006. This metric shows that for all orders, regardless of size, the average retail investor in our sample used to pay roughly 15% more than the bid offer spread to complete their trades. Today, however, the same investors pay over 15% LESS than the spread.

*Source - RegOne Solutions copyright 2015

What is NOT obvious about these numbers is why it has happened. The fact is that retail investors have little to fear from the advance of technology, because it works to their advantage. The top wholesale market makers are based on the same technology platforms often derided by critics. These firms employ state of the art technology as a competitive tool to provide better executions for their retail brokerage clients. While we are not claiming that market makers are altruistic, we are making the point that retail investors directly benefit from the technology they employ. To be clear, the statistics that RegOne generates that prove the benefits to retail investors cannot be rigged (as some uneducated critics have falsely asserted). At RegOne we base our execution analysis on the last quote of the time interval before these firms receive each order. This makes it impossible to manipulate the price improvement stats.

In order to underscore this point, I would like to issue a public challenge to Mr. Lewis or any other critic that asserts that retail investors are being taken advantage of. In particular, I challenge them to name a particular firm who they are willing to assert "front runs" individual investors "after the button is pushed". If Mr. Lewis is willing to name any of the top six market makers, as identified by Rule 605 reports, as doing this, I will happily appear on CNBC with him to provide statistical evidence of his duplicity.

Now, back to Mr. Chilton. What he gets wrong is that there areconflicts of interest and there is too much opacity in the market for institutional investors. The conflicts of interest I am referring to were spelled out in my recent commentary titled "Dirty Rotten Secrets" . They occur when broker dealers make design choices in their algorithms or smart order routers, based more on the different fee or rebate structure of venues, instead of the predicted execution probability or market impact of different routing choices. The fact that these routing choices are often hazy is the other problem. The results of Nasdaq's recent experiment to test lower access fees and rebates for a handful of stocks bears this out: Nasdaq lost 2.9% market share as routers sought more favorable rebates at other venues.

Rule 605, which is designed to show the execution quality of all market centers, excludes over 65% of executed volume. Market centers, including those run by the large broker dealers, are allowed to exclude all the "child orders" that can be linked to discretionary institutional orders. Thus, all orders routed by algorithms, on behalf of larger orders or institutional clients, can potentially be excluded from the execution quality reporting of Rule 605. Rule 606, which is designed to provide disclosure on order routing practices, excludes a majority of all routed orders from reporting. While that statement is likely surprising to many readers, orders that are routed, but not executed are not subject to reporting.

To illustrate why this is problematic, I looked at the most recent month of 605 data and calculated the ratio of routed shares to executed shares. For this sample of orders, which generally has a higher percentage of executions to orders than the institutional order flow that is excluded from Rule 605, the ratio is roughly 7:1. That implies that over 85% of order routing is not disclosed by Rule 606. Further, Rule 606 does not require disclosure of either fees or execution quality and does not require any segmentation of order types utilized. Lastly, Rule 606 does not require stock exchanges to report, despite the fact that they are among the largest order routers in the marketplace.

My contention is that these exclusions have contributed heavily to the climate of mistrust among institutional investors and critics of modern markets. I do not think that it is at all surprising that retail investors have seen dramatic improvements in their execution quality, while many institutional investors claim that they have not. While it is not at all clear where to place blame on the perceptions of market problems, it seems quite obvious that improving transparency, by eliminating the gaps mentioned here, would be a good start.

I firmly believe that "fixing" both Rule 605 and 606 should be a priority for the SEC.

I have pointed this out several times in my commentaries and numerous others have made the same point. Earlier this year a petition with the SEC was filed by BATS, making this same point. If the exemptions in the rules were eliminated, the reporting categories expanded, and the relevant fees, rebates and execution statistics were disclosed, institutions would start to gain some of the advantages that disclosure has provided to retail investors.

These changes would also enable firms, such as ours, to help participants make sense of the data and develop actionable plans for improving their execution quality. It would also focus the market micro-structure conversation on meaningful data and analysis rather than innuendo and half- truths by uninformed critics. The bottom line is that transparency, enabled by technology, is the best possible solution. I believe that the SEC and FINRA understand this, so we should help them focus their rule-making towards encouraging more transparency, instead of responding to various lobbying or legislative efforts to push anti- competitive rules.

In this regard, I agree wholeheartedly with Mr. Chilton.

David Weisberger, Managing Director, Trading Services at Markit

Posted 16 March 2015

S&P Global provides industry-leading data, software and technology platforms and managed services to tackle some of the most difficult challenges in financial markets. We help our customers better understand complicated markets, reduce risk, operate more efficiently and comply with financial regulation.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19032015-in-my-opinion-dear-michael-lewis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19032015-in-my-opinion-dear-michael-lewis.html&text=Dear+Michael+Lewis","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19032015-in-my-opinion-dear-michael-lewis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Dear Michael Lewis&body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19032015-in-my-opinion-dear-michael-lewis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Dear+Michael+Lewis http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19032015-in-my-opinion-dear-michael-lewis.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}