Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ARTICLES & REPORTS

Nov 22, 2021

Should unsustainable food be taxed?

- Taxing unsustainable food could help supermarket prices finally capture the 'true cost of food'

- Advocates argue that revenues could help farmers adopt greener practices

- Opponents fear such a policy will lead to carbon leakage and undermine farmers' competitiveness

- COP26 saw the tax debate focus on food's carbon emissions - with livestock products singled out

- Uncertainty remains on how to compare different farming systems and ensure a fair tax

- Policymakers are still likely to engage with the topic as they search for solutions to meet climate targets and make sustainable food more affordable

Bringing the food system within safe environmental limits requires huge changes to modern farming, with some arguing that a tax on unsustainable products is one of the most effective incentives to guarantee that transition happens.

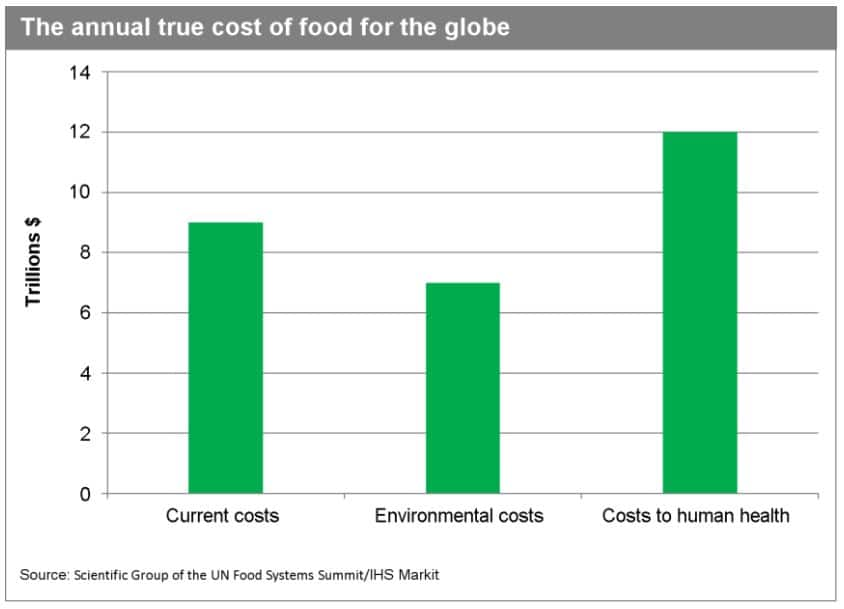

In June 2021, scientists advising the UN said such a tax could help supermarket prices finally capture the 'true cost of food', estimating that currently markets exclude $7 trillion in costs from a degraded environment and $12 trillion from an unhealthy society. Advocates for such a tax add that revenues can be redirected back to farmers where they can fund the adoption of greener practices. Still, the concept of an unsustainable food tax is a controversial one, particularly among farming and business groups who argue it discriminates against certain producers, while also raising doubts that such a fiscal policy can reflect the nuances of regional production.

That has seen taxing unsustainable food become a high-risk option for politicians - on one hand it could stimulate more sustainable production and consumption while meeting a range of green targets, but on the other hand it risks hurting certain food producers and undermining their competitiveness. It makes the path forward a perilous one, but recent trends may end up pushing decisionmakers ahead whether they want to move or not.

Carbon focus emerges at COP26

Taxes on 'unsustainable' foods could discourage their consumption, but the reality of taxing food based on this notion is complex - considering the amount of economic, social and environmental aspects in a product.

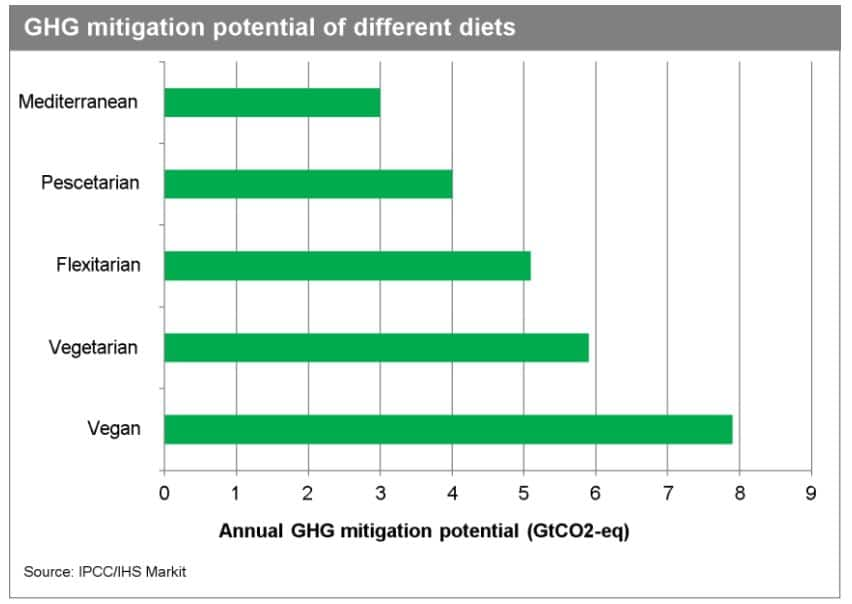

The range of issues and definitions when producing and consuming food means the debate around taxing unsustainable products has generally centred around one of the most pressing topics - climate change. The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which sets the science for the Paris Climate Agreement to limit global warming to a 1.5C degree scenario, found that meeting this objective requires a 50% decrease in the consumption of foods like meat, dairy and added sugar, alongside doubling plant-based foods. The climate scientists also highlighted taxes as one of the most promising solutions to reduce food system emissions in line with this pathway.

That has given momentum for a sustainable food tax based on greenhouse gas emissions, and even more so as countries commit to reducing their carbon footprint further following COP26, the UN's climate summit in Glasgow. A group of 90 organisations calling themselves the 'Carbon Pricing for Food Coalition' used COP26 as a platform to call on the 50 biggest meat consuming countries to back a carbon price for food, including the US, EU and China.

"Taxation policies are effective when you want to reduce consumption of something," said the coalition's coordinator Jeroom Remmers at COP26, arguing that fiscal policies have helped reduce the use of fossil fuels, alcohol and tobacco. Remmers went on to say that more policies are needed to curb meat consumption and its associated emissions, which he says are rising at 4% per year worldwide. "If we don't tackle this problem, we will never realise the Paris Climate Agreement goals," he added.

Responding to the coalition's letter, Lucas Pre, policy officer at the Dutch Agriculture Ministry, said it comes at the "right time" and hopes it will lead to more engagement from governments on the topic. "The role of true [food] pricing to reach sustainability goals is a very interesting approach," Pre said at COP26, adding that when consumers visit the supermarket they need to know "what the production of meat and dairy means for the living environment".

Dutch support for taxes seem to be growing as Pre's comments come on the back of his country's agriculture minister voicing her support for some sort of sustainable food levy. And the Netherlands is not alone here either - ahead of the COP26, UK Secretary for Food and Rural Affairs George Eustice said Britain will "start to move into the realms of things like carbon taxes" to improve farming's environmental impact.

However, this rhetoric does not come without its risks and Eustice's comments sparked outrage among the UK agriculture sector, which quickly pushed back against such a policy idea. The National Farmers Union of England and Wales (NFU) argued that the British livestock sector produces some of the most sustainable food in the world and that a carbon tax would undermine its competitiveness and ultimately result in farmers going out of business.

The NFU's concerns appears to have reached Eustice who since backtracked and ruled out a carbon tax on red meat.

Level CO2 playing field

The sensitivity of a carbon tax for food reveals one of the biggest obstacles standing in the way of such a fiscal policy based on carbon emissions - the need for a level playing field. The highly competitive nature of international food markets has seen agri-food stakeholders argue that if one region introduces any sort of sustainability tax domestically, then it must be applied to imports too.

This carbon leakage narrative plays out regularly in sustainable farming debates, particularly when trade agreements have given beneficial market access to products that can come from less sustainable food systems. And one place where these arguments are very common is the European Parliament's Agriculture Committee (AGRI), where policymakers recently started to push for farming products to be covered in the EU's new carbon border tax on high-emitting imports.

In October 2021, AGRI finished its draft opinion on the European Commission's proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and proposed one amendment to the EU executive's legal texts that called for agricultural imports to be included in the future levy. In response, the Commission told AGRI that the CBAM cannot single out specific products or else the carbon levy risks going up against WTO rules as well as derailing the EU's own climate commitments.

There were also several opposing AGRI members who were sceptical that such a tax proposal can get enough political support since it is still unclear how such a levy could measure the carbon footprint of all the different systems in the world, let alone those within the EU.

The challenges of fair taxation and affordability

Fairness is a far-reaching issue for an unsustainable food tax, whether that's for domestic products and imports or consumers - even if it focuses on just one such indicator like greenhouse gas emissions, or a market segment, such as beef and dairy.

For instance, the UN's Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) attributes livestock to 14.5% of all greenhouse gases. These figures are based on a global perspective which takes in the best and worst performers worldwide, meaning a carbon price based on that approach, albeit very unlikely, shows how such a levy could unfairly treat some livestock farmers, such as those in Europe where livestock accounts for about 8-9% of the bloc's total emissions.

"We have to be really careful when we make generalisations," said Steven Thomson, Agricultural Economist at the Scottish Government's Strategic Research Programme.

Thomson explains that going down the route of a carbon tax for food requires discussions about a range of supply chain externalities to ensure fair treatment, such as the local environment, processing and transport, and then comparing this analysis to other sectors and their share of the economy's carbon footprint.

Without this information, Thomson says policymakers could put forward "blunt" and "generic" carbon taxes. "We have to be really smart on how we address this climate issue when signalling for consumers to reduce their emissions," the economist explained, adding that direct payments to farmers and green investments are better positioned to make sustainable food cheaper for farmers.

"We're giving farmers quite a lot of [public] support in order to maintain income because of fluctuating market prices," he said. "We should be utilising that as much as we can to drive behavioural change."

In an ideal world, every farmer would get a different carbon tax bill, according to Jeroom Remmers from the Carbon Pricing for Food Coalition, who also defends some sort of a general approach because it can still collect and redistribute revenues in a way that helps food producers adopt more sustainable practices while also making the right food more affordable for consumers. "57% of French and German consumers support our proposal of a 40% tax on meat," he added.

Affordability will remain key for making sustainable food systems a reality. Half of UK consumers are still unwilling to pay extra for more sustainable products, according to survey of 3,000 consumers conducted by ASDA, a British supermarket chain. Asked what would help them shop more sustainably, 45% said logos highlighting greener choices and 56% said greater choice, but 76% said lower prices. ASDA's senior director of commercial sustainability Susan Thomas concluded their research shows "consumers from all backgrounds care about sustainability but many cannot afford to buy greener products".

This means that without some sort of fiscal change, most countries' diets will continue to contribute to climate change for the time being and that could push policymakers towards measures that can see the public put more money where their mouth is. Add climate targets to the mix and policymakers are likely to engage with the tax topic even further - which means others may need to take their own stance, whether they want to or not.

This article was published by S&P Global Commodity Insights and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fesg%2fs1%2fresearch-analysis%2fshould-unsustainable-food-be-taxed.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fesg%2fs1%2fresearch-analysis%2fshould-unsustainable-food-be-taxed.html&text=Should+unsustainable+food+be+taxed%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fesg%2fs1%2fresearch-analysis%2fshould-unsustainable-food-be-taxed.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Should unsustainable food be taxed? | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fesg%2fs1%2fresearch-analysis%2fshould-unsustainable-food-be-taxed.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Should+unsustainable+food+be+taxed%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fesg%2fs1%2fresearch-analysis%2fshould-unsustainable-food-be-taxed.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}