Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Container shipping handles 45% of global trade. How it will decarbonize is an open question.

Published: February 21, 2024

By Peter Tirschwell, Turloch Mooney, Chris To, and Mayank Agarwal

Highlights

Container shipping provides a case study of the challenges in decarbonizing maritime transport. The highly competitive industry is responsible for transporting 45% of global trade by value, accounting for 0.75% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has mandated that the shipping industry achieve net-zero GHG emissions by or around 2050. This will result in higher industry costs and require shipping companies to find efficient ways to spread these costs across the supply chain.

However, there are concerns that the IMO may not approve a meaningful carbon tax, potentially leaving the industry ill-equipped to finance the transition. The next two years will be critical for the UN agency to develop regulations that can create a viable pathway toward the 2050 decarbonization target.

The year 2023 was a milestone in container shipping. All ships ordered with a capacity greater than 5,000 twenty-foot equivalent units will be able to operate on alternative fuels such as ammonia and methanol, reflecting the growing momentum in the sector's decarbonization journey. Still, questions surrounding key aspects of the plan remain, starting with who will bear the cost of the massive bill that will come due in the next few decades.

The shipping industry is working on reducing its carbon footprint. Though the process is underway, the outcome is uncertain in terms of timing and methods.

The container shipping sector presents multiple challenges. Container shipping transports about 45% of the value of international trade, with two-thirds of all seaborne trade by value being containerized, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development. It is the primary mode of transport for consumer goods, manufactured goods, specialized agriculture and specialized chemicals. For decades, container shipping has absorbed cargo previously moved by other maritime transport modes, including bulk, breakbulk, refrigerated and roll-on/roll-off.

Approximately 3% of GHG emissions come from the maritime industry, while container ships account for 25% of maritime emissions, according to industry data. Maritime was not mentioned in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, leaving the IMO with the responsibility of decarbonizing the sector.

Unique among hard-to-abate sectors, maritime is an inherently transnational industry regulated by a global agency that has long created and enforced safety, security, operations and emissions rules. This is seen as an advantage because it provides an opportunity to create a global pathway to decarbonization, which is not available in other sectors. In mid-2023, the 175 member states of the IMO unanimously agreed to more ambitious global decarbonization goals. The agreement replaced the prior goal of achieving a 50% reduction in carbon emissions by 2050 (versus 2008 levels) with a new goal of eliminating carbon emissions "by or around" 2050, in line with the Paris Agreement's objective of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C above preindustrial levels.

The agreement included waypoints, such as committing international shipping to zero or near-zero carbon energy sources for at least 5% of energy use by 2030 and reducing total GHG emissions by at least 20% by 2030 and 70% by 2040 compared with 2008 levels. To ensure these goals are met, the IMO launched a two-year process of writing and approving regulations to establish a pricing mechanism for carbon and implement measures like fuel requirements.

The process of decarbonizing maritime, as for all other sectors, comes with significant costs. It is unclear who will bear that cost, as pricing for such things as zero-carbon fuels is set by the market, not by regulation. Efforts to decarbonize have involved investments by container lines in eco-friendly ships where operation and fuel costs can be absorbed with marginal financial implications for the carriers. But as the carriers scale up, the cost will increase exponentially and would need to be shared with cargo owners and their customers.

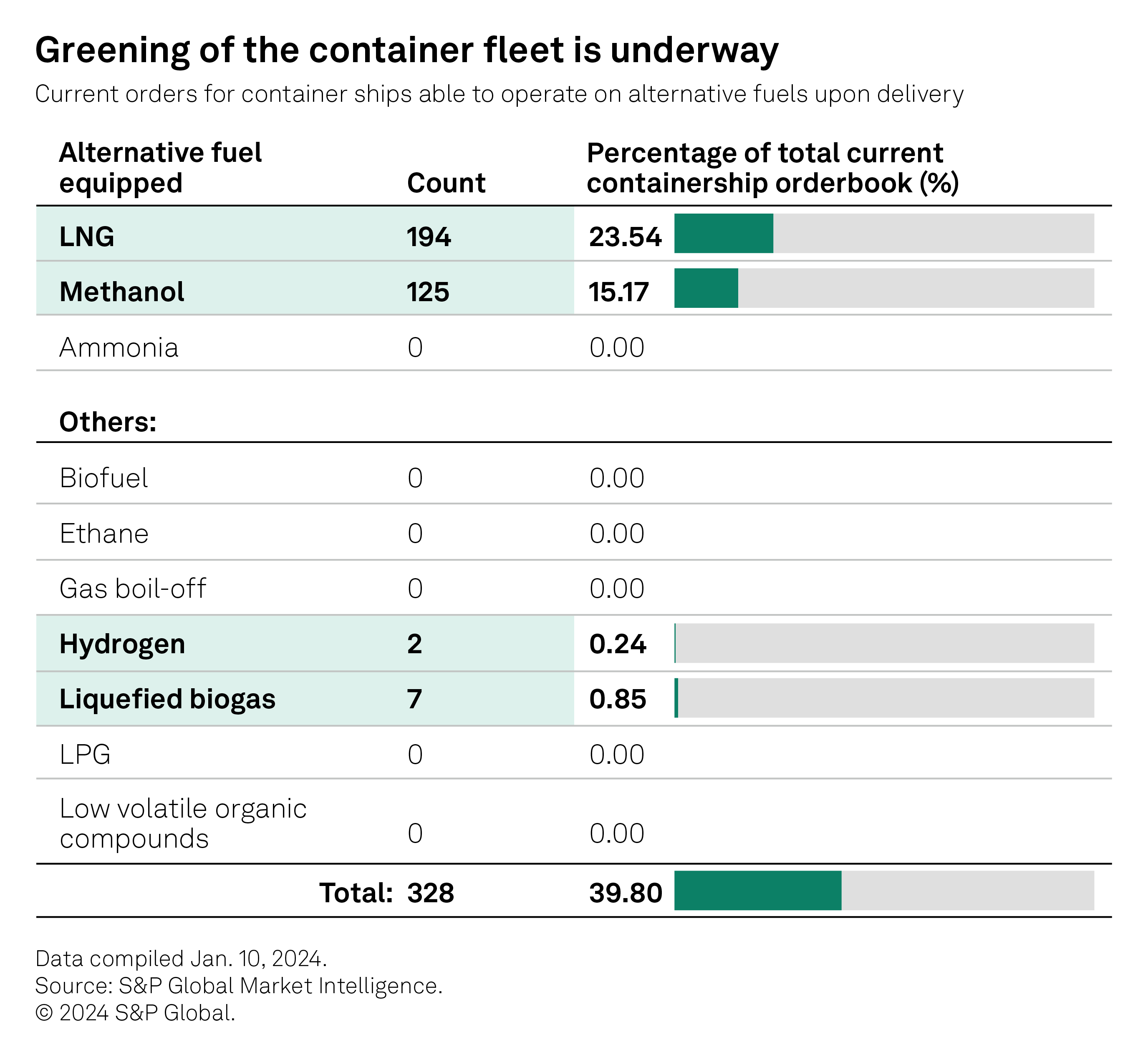

The container industry's first step toward decarbonization was to use LNG, which emits 25% less CO2 than traditional bunker fuel. However, the impact of LNG is still minimal; only 74 container ships run on LNG, representing just over 1% of all container ships in operation, based on S&P Global Market Intelligence data. Another 186 LNG ships are on order, meaning LNG will represent roughly 4% of container ships in operation once those ships are delivered. LNG ships on order are nearly a quarter of container ships under construction, which shows that ship owners are increasingly emphasizing orders for eco-friendly vessels.

Green ammonia and methanol are two potential zero-carbon fuels that could achieve scale. Both are chemicals produced from renewable energy sources. While batteries can operate on small vessels such as ferries, they are considered inadequate for deep-sea ocean shipping due to their weight and limited energy density compared with other energy sources.

Methanol has progressed faster as a zero-carbon fuel compared with ammonia, which is highly toxic and will require extensive safety precautions. As of late 2023, one methanol-powered container ship was in operation. Orders have been placed with shipyards for 125 container ships that can operate with methanol upon delivery and another 50 ships that can be retrofitted to use methanol later, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

There are no existing orders for ships that can be powered by ammonia upon delivery, but orders have been placed for 50 ships that can be converted to ammonia power post-delivery. Ammonia is moved today by ship as cargo and has influential advocates within the maritime industry. Less than 2% of container ships in operation are running on alternative fuel, nearly all of that LNG, but a rapid scaling-up is underway, with about 40% of all container ship orders being for ships that can run on reduced or zero-carbon fuels upon delivery. All container ships ordered in 2023 with a capacity greater than 5,000 twenty-foot equivalent units will be able to operate on alternative fuels either upon delivery or later.

As the industry scales up, the question of who pays for the conversion of the fleet and bunkering facilities is emerging as a key issue. A UN Conference on Trade and Development report said that up to $28 billion would be required annually to decarbonize ships by 2050, in addition to up to $90 billion to build the infrastructure to store, deliver and transfer zero-carbon fuels. Theoretically, the cost should be shared across the value chain, but in practice, accomplishing that is far from simple or assured.

There is limited evidence, at least so far, that retailers, manufacturers and other shippers are willing to pay higher-than-market prices to ship goods using alternative fuels, except for a few pioneers. Despite S&P Global Sustainable1 reporting that about 4,000 companies have publicly committed to reducing Scope 3 emissions, which includes outsourced maritime and other forms of transportation, only a few large container shippers have agreed to pay above-market rates for zero-carbon solutions. Among them are members of a buyers' association led by the Aspen Institute and including Nike, Levi Strauss, Tchibo and Schneider, which has pooled members' cargo and is seeking competitive bids from ocean carriers for zero-carbon transport.

For most cargo owners, the voluntary system alone will not achieve the IMO's revised targets. The IMO must introduce regulations within the next two years to bridge the gap between zero-carbon and traditional bunker fuels. A key question is whether IMO member states can agree to a carbon price that is high enough to neutralize or mitigate the significant cost differential between the fuels. As of October 2023, the effective price of methanol was more than six times that of low-sulfur fuel oil, while the effective price of ammonia was nearly nine times the price of low-sulfur fuel oil, according to one ocean carrier's analysis. Data from S&P Global Commodity Insights shows "bio-bunker" fuel prices are approximately 40% higher than crude oil-based products.

Container line companies have introduced green shipping services that allow shippers to reduce their CO2 emissions through a process known as carbon insetting. However, interest in these services has been modest at best.

The carbon price debate within the IMO is controversial and emotional. Two primary carbon pricing mechanisms — the bunker levy and cap-and-trade system — face significant opposition. For example, some remote island nations fear that a high carbon price will lead to higher transport costs and ultimately higher consumer prices, akin to a transnational tax. Negotiators will need to agree on a common strategy by spring 2024 to meet the IMO's timeline for new regulations.

An alternative way to reach those goals is by setting a global fuel standard, one that is neutral regarding fuel type but mandates a progressively larger zero-carbon component of fuels used by the global fleet of 50,000 deep-draft vessels.

But that option, while politically less divisive, still requires container lines to pass along the cost of zero-carbon fuels, which are certain to be higher than for traditional bunkers because of limited supplies, the multistep refining process required to produce them and competition for those fuels from other industries.

A preview of such a scenario came in December 2023 when China did not recognize additional fees introduced by container lines in accordance with the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), which will cover maritime transport from Jan. 1, 2024. China saw the cost as an unfair tax on its exporters, preventing carriers from passing along decarbonization-related expenses as an additional surcharge. Despite this, several carriers have shown their intent to publicize these ETS surcharges on at least a quarterly basis to shippers globally.

With the EU ETS phase-in period in its infancy of charging 40% of half of inter-EU emissions in 2024, S&P Global Commodity Insights expects the impact on overall shipping trading patterns to be minimal in the near term. However, ETS fees of €9.00-€83.00 per twenty-foot equivalent unit as of November 2023, depending on the carrier and route, will pale in comparison to the costs of zero-carbon fuels. This reveals the long-term liability carriers face if they lack a clear mechanism for sharing the costs with customers. The result could be a structural squeeze on an industry that has historically been minimally profitable, potentially leading to further consolidation.

A comparison of the prices for Asia-to-Europe container shipping and EU ETS permits shows the complexity facing supply chain operators. The ETS price is a function of the power-generating industry due to its share of issued ETS permits, making hedging a complex exercise for logistics firms including shipping companies.

ETS and container prices have experienced significant volatility over the past three years. Container shipping rates in mid-2021 reached 14 times their 2019 level, eventually dropping to their 2019 average in November 2023. Also, in late 2023, rates rose to 3.6 times their 2019 level within a few days following attacks against container ships passing through the Red Sea.

ETS prices have increased steadily due to elevated natural gas prices versus coal. The program's steady expansion to include a wider range of sectors, along with the removal of freely allocated permits, has left prices at 3.2 times their 2019 average.

Concerned about the prospects of a meaningful carbon tax over the next two years, carriers are escalating a campaign to argue the case in public. If the primary mechanism to drive decarbonization in container shipping is a fuel standard, it could be difficult for the profit-challenged industry to pass along the higher costs of zero-carbon fuels. This could be a game changer, not just for the sector but for containerized supply chains writ large.

S&P Global Market Intelligence

Sidebar: Container ports + emissions management

Ports and terminals are primary factors in the container decarbonization agenda. Container ships can spend up to 20% of their total rotation time in ports. In 2019, the IMO passed a resolution encouraging ports and shipping lines to work together to reduce GHG emissions.

Ports can help in the transition to clean energy by providing refueling points for green fuels and shoreside power for ships at berth. They can also work with shipping lines to optimize port calls and move toward systemwide, just-in-time ship arrivals. Knowing in advance the time ships can berth enables them to slow down en route, conserving fuel and limiting emissions.

Container services often have fixed sequences of port calls and terminal berthing windows, which makes it predictable for shippers, shipping lines and ports to plan and allocate resources. However, global port call processes are inefficient and usually subject to delays and schedule disruptions. In 2022, about 30% of global container port call time was spent on pre-berthing processes, and ships had to wait an average of eight hours offshore for each call, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Delays occur at all stages of port call processes, from preparations to work ships, to loading and unloading containers, and further to clearing ships for departure. The global best practice to complete processes before moving containers after a ship berths is about 20 minutes, but at hundreds of terminals globally, ships are routinely alongside for several hours before cargo operations start. When network volumes rapidly increase, even ports functioning efficiently can quickly struggle with additional demand, causing congestion that can spread globally.

Addressing inefficiencies can increase predictability and reduce wasted port hours. Ship operators can invest that time in subsequent journey legs to control speeds and curb fuel burn. This can lessen incidents of ships needing additional fuel to maintain schedules or recover services, which can involve higher sailing speeds, fuel consumption and emissions.

One solution is to analyze and monitor port time performance to uncover gaps and improve processes. Fit-for-purpose infrastructure and suitable labor are critical components, but globally, digitization presents an opportunity to transform operations by supporting higher levels of collaboration, data-sharing and decision-making around port calls.

Vice President, Maritime & Trade

Renewable natural gas and hydrogen: fuels of the future for transportation decarbonization

Can the Shift to Net Zero Accelerate Amid Growing Headwinds?

Singapore's EMF steps up decarbonization, to include LNG bunkering in portfolio

Listen: 2024 trends that sustainability leaders are watching

Next Article:

Labor: A critical component of supply chains under growing pressure

This article was authored by a cross-section of representatives from S&P Global and in certain circumstances external guest authors. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent and are not necessarily reflected in the products and services those entities offer. This research is a publication of S&P Global and does not comment on current or future credit ratings or credit rating methodologies.