Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

By Robert Litan, Ella Bell Smith, Matthew Slaughter, and Robert Lawrence

Highlights

This is the third chapter in a series of content related to Entrepreneurial Leadership Must Help Meet America’s 21st Century Challenges in a Post-Pandemic World

Chapter One: Introduction – Major 21st Century Post-Pandemic Challenges

Chapter Two: The Power and Limits of Federal Policy

Chapter Four: Barriers to Social and Policy Entrepreneurs

Chapter Five: Reducing Barriers to Effective Social Policy and Policy Entrepreneurship

Chapter Six: Changing Mindsets

Join S&P Global Sustainable1 for the next episode in our ‘Beyond ESG’ series as we sit down with the authors of the report. Register here to join the discussion or receive the on-demand replay

America is changing in many ways, as it always has. Change happens for many reasons – because of constantly evolving technologies, changing demographics, policies of governments at all levels, and enterprising for-profit and non-profit entrepreneurs and companies. In this section, we focus on those entrepreneurial efforts. We do not attempt to provide a comprehensive account – that would take one, or more likely, several books. But we can and will paint a broad picture of concrete action by way of illustrations.

The central message readers should take away from this survey is that progress is being made. While it is not enough and it is not happening rapidly enough, the fact of progress must be recognized, and it should inspire those who have doubts about our future.

At the same time, entrepreneurial leaders in each of the non-federal sectors face constraints which currently limit their ability to be as effective as they could be in addressing our national challenges. In subsequent sections we describe what those constraints are and then how they can be relaxed.

In addressing whether the U.S. is on the verge of turning the corner from an “I” centered society to the quasi “We” nation that existed from roughly the early 20th century until the 1960s, Robert Putnam draws on what helped turn the country toward a similar course in the late 19th century, toward the more progressive, community-based society the U.S. later became.

Most importantly, Putnam shows how change was led by entrepreneurial leaders – people who just couldn’t stand idly by during the gilded age of the 19th century and do nothing in the face of what they saw as injustice. And so these names entered the history books, as pioneer reformers: Frances Perkins – who was horrified by the fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory that killed 146 innocent souls – committed her life to changing working conditions at crowded, unsafe factories and ultimately became the first women to hold a Cabinet position as FDR’s Labor Secretary; Jane Addams, who founded the American Settlement House movement to advocate for immigrants and the urban poor; Lillian Wald, who championed human rights and helped bring health care to tenement-residents in New York City; and John Dewey, who reformed American education to produce engaged citizens.

In our country today, there are many nationally known figures working to address each of the four major challenges that our society currently confronts. In our accompanying Profiles in Entrepreneurial Leadership, we describe the efforts of multiple individuals and their organizations that are doing similar things, but currently operating under the national radar.

In the next two sub-sections, we discuss more broadly how entrepreneurial leaders at the community level and in the business community, respectively, are helping society meet each of its four major challenges.

There is an important reason why the partisan polarization that has infected and defined politics and governance at the national level, at least so far, has not been as evident at the local level: the daily public issues and problems that citizens and their local governments must deal with are not partisan. As evidence, consider the analysis of a 2018 You Gov survey of representative respondents in eight metropolitan areas across the United States by Amelia Jensen and three colleagues (including one of co-authors of this study, Slaughter).[i] The authors find that even among those who strongly identify with one of the two major political parties, policy preferences on a variety of local issues do not statistically or substantially vary by political party affiliation. [Jensen et al, 2020]. The local issues surveyed run the gamut: tax incentives and subsidies designed to attract or retain businesses, local training and entrepreneurship support programs, educational spending, and spending on infrastructure and crime prevention.

The authors offer several reasons for their findings. One factor is that because cities compete with others for businesses and high-income residents, they are likely to adopt similar policies, regardless of the party affiliation of their leaders. Another factor is that voters have fewer “elite cues” to know which local policies may be associated with which party, which matters more for Congress and the Presidency. Working against these factors is the possibility that the size of government, at any level, is a clear point of distinction between the two parties. At the end of the day, however, the non-polarizing factors, at least as of 2018, predominated as an empirical matter, which is heartening.

Of course, the business climate – and its ability to generate broadly shared prosperity – in any locality is affected by national trends and factors, such as the overall macroeconomic climate, technological changes that tend to favor skilled over unskilled workers, climate change, and most recently pandemics, which no city or rural location can control. Likewise, a broad range of federal policies and spending patterns, especially on infrastructure and R&D, influence how and where cutting-edge technologies are developed and scaled up.

Still, many communities have found better ways to swim with the national tides, or to compensate for them if so required, than others. Citizens and local government officials can learn important lessons from these efforts.

In their groundbreaking book, The New Localism, Brookings’ Bruce Katz and Drexel University professor Jeremy Nowak, profile several medium-sized cities – Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, St. Louis, and Cleveland – that have been hammered by the decline of their signature firms but are reinventing themselves through the emergence or growth of firms in other industries. [Katz and Nowak]. Journalists Deborah and James Fallows survey many other smaller communities that are doing the same thing in their book Our Towns, which has been adapted for television in an HBO documentary of the same name. [Fallows and Fallows]. Two are especially noteworthy. Greenville, South Carolina was revitalized by downtown reconstruction centered around the river that runs through the city and investments in that city’s medical facilities. Burlington, Vermont was changed forever by then mayor (now Senator) Bernie Sanders, who created a “land trust” that effectively provides a permanent endowment to support low-cost housing, encouraged local small businesses (rather than attempting to recruit relocations), and launched after-school programs for the city’s students. All these initiatives have made the city a nice place in which to live, attracting and retaining tech companies and their highly skilled workforces.

The authors of these two books distill many specific-lessons from these community-based efforts, though they also differ in their details. One is that immigrants – not just highly skilled scientists and entrepreneurs (often one and the same) – but also those with lesser skills but a strong work ethic, have been instrumental in reinventing communities across America. Another lesson, hard to “bottle,” is an entrepreneurial culture, reinforced by supporting networks of professionals who assist new, growing companies and their founders. [Agtmael and Bakker, Feld and Hathaway].

But perhaps the most important lesson is that no community can be successful, whether once down and out, or a “superstar” city on the cutting edge, without entrepreneurial leaders in both the private and public sectors. These individuals are building new companies or expanding existing ones and come from all backgrounds. They work in concert with entrepreneurial public officials, typically mayors, to generate economic opportunities not only for their employees and their suppliers, but also workers in service industries that grow along with them.

Given the many changes in the economy and society likely to be triggered by the COVID pandemic, cities will need forward-looking leaders in both the public and private sectors, both to respond creatively to a post-pandemic world where fewer people may be working every day downtown [Loh and Kim], as well as to anticipate future developments that will affect both downtowns and suburban areas. These actions almost certainly will require retraining of workers to provide them with the skills required by new and growing firms that thrive in the wake of continuing disruptions. Federal policies can help in this regard, funding retraining initiatives and providing a federal “heartland visa” program (work visas granted on condition that applicants work for a certain length of time in given locations) that further enable immigrants to help revitalize areas around the country where they are welcomed. But federal help alone cannot guarantee local success and inclusive opportunities without local leadership in both the private and public sectors.

We do not claim that every city can replicate the successful comebacks or adjustments cited here. The histories, culture and makeup of cities and towns differ too much across America to endorse such a bold claim. But the fact that some cities have turned things around at least should provide hope that others can do so as well.

The corporate form of business organization, which evolved from “joint stock companies” invented in Europe but taken to new heights in the United States beginning in the early 19th century, is one of the most powerful legal inventions of all time and has given rise to what we now call “capitalism.” The corporate form rests, of course, on the legal doctrine of limited liability, or the notion that shareholders are responsible only for the amounts of the shares they purchase in a company, not for anything more. Limited liability dramatically reduced the risk of financing companies, which facilitated the commercialization of innovations, while allowing firms to scale the innovations most in demand rapidly by giving companies access to what have become vast pools of equity capital.

Limited liability is a key part of U.S. history and it helped unleash remarkable growth in living standards. Economic historians have documented that for thousands of years until the beginning of the industrial revolution, average living conditions throughout the world barely budged. Since about the year 1800, economic growth in the U.S. and many other countries has surged, driven largely by a continuous series of innovations – in communications, information, transportation, and manufacturing, among others – that have created our modern world.

This isn’t to say that growth has been continuous or that its fruits have always been widely shared; in various periods over the past two centuries, that hasn’t been true. Moreover, as we have already noted, in the wake of the pandemic, the nation faces more challenges than just economic growth.

How might corporations help meet today’s challenges? For many decades, some have argued that private firms serve society best by only pursuing profit: inventing and then selling goods and services that consumers want, at prices and with the quality dictated by competition and regulations in the marketplace.

But no company operates in a cultural, political, or social vacuum. Norms change over time, as do the tastes and preferences of consumers, workers, and investors. Today it is simply a fact of life that for many companies, where they officially stand on various political, cultural, or even religious issues matters to many of their consumers, workers, and even investors. Some companies and business organizations have embraced this new reality and use it as part of their overall strategy. Others have been induced by events or one or more of their stakeholder groups into taking public stances or even actions, such as shifting locations of major events. For example, in 2017, the NBA moved its All-Star game out of Charlotte in response to North Carolina’s transgender bathroom law. Earlier this year, Major League Baseball moved its All-Star Game out of Atlanta in response to Georgia’s new voting laws. Shortly thereafter, CEOs and executives of over 100 companies issued public statements condemning the Georgia voting laws and similar efforts elsewhere.

In August of 2019, the CEOs of 181 members of the Business Roundtable revised the organization’s statement of the purpose of a corporation. In place of the former primacy given to maximizing shareholder value, the new statement announced that in addition to serving the interests of shareholders, corporations should also serve the interests of other stakeholders: workers, customers, suppliers, and local communities [Business Roundtable].

In our view, taking account of the interests of multiple stakeholders is not inconsistent with maximizing shareholder value. To the extent that various stakeholders care deeply about a corporation’s public stance and on actions taken with respect to certain issues, political or otherwise, then what a corporation does or does not do on these questions can clearly affect the profitability and hence the shareholder value of the organization. In this way, there need not be a tradeoff between maximizing shareholder value and meeting the interests of other stakeholders—although there almost certainly will sometimes be tradeoffs among stakeholders that corporations must weigh.

Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase, put it well in his 2021 letter to the company’s shareholders:

“Frankly, we punted too much of the responsibility to our government. But we are partly responsible – for we prioritized shareholder interests and sometimes narrow self-interests over creating broader opportunity for all in America. Successful businesses can literally and figuratively “drive by” our worst problems (think inner cities) and still thrive. These large companies can and should be more aggressively part of the solution because they can uniquely help with job planning, skills training, infrastructure investment and community development. And doing so, over the long run, is both morally right and commercially right because it will be good for business. (emphasis added).” [Dimon]

The responsibilities of CEOs, their management teams, and their boards of directors today are much more complicated than just delivering quality products and services at market prices. In today’s complex world, these are realities with which every leading company must wrestle [Seib]. According to the 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer, 87 percent of those surveyed around the world agreed with the statement that “Stakeholders, not shareholders, are most important to long-term company success,” and 73 percent agreed that “a company can take actions that both increase profits and improve conditions in communities where it operates.” Large majorities of employees also want the CEOs of companies to speak out on a range of public issues, including income inequality, diversity, and climate change [Edelman Trust Barometer, 2020]. More broadly, despite the drop in trust in multiple institutions around the world since the pandemic, business is the most trusted of the four major institutions surveyed – more than NGOs, governments, and the media. In the U.S. this ranking holds regardless of for whom one voted in the 2020 election [Edelman Trust Barometer 2021].

Companies are doing a lot more than just talking about one or more of the four societal challenges we address in this paper: they are taking meaningful actions. Below we provide some examples of innovative and inspiring actions—examples that are certainly not meant to be exhaustive but instead illustrative of progress that is happening.

Expanding Opportunity: Rising regional and personal income disparities, which as noted earlier are closely related, can only be halted, and ideally reversed, if more workers meet the changing skill requirements of employers. By one estimate made before the major disruptions of the COVID pandemic, 30 percent of the existing U.S. workforce (and over 375 million workers globally) will have to change jobs or upgrade their skills by 2030 [Manyika, et al].

Since the pandemic, according to a Prudential survey released in June 2021, an even larger share of the workforce – over half – wants to change jobs, ideally in different industries or occupations which can give workers more job satisfaction or higher pay, or both [Pandey]. This represents a sea change in what workers want. In pre-pandemic times workers threatened by technological change, trade, and other disruptions tended to want to keep their current jobs. Now, with so many wanting to leave their jobs to try something else, a central policy challenge is how to help them do so.

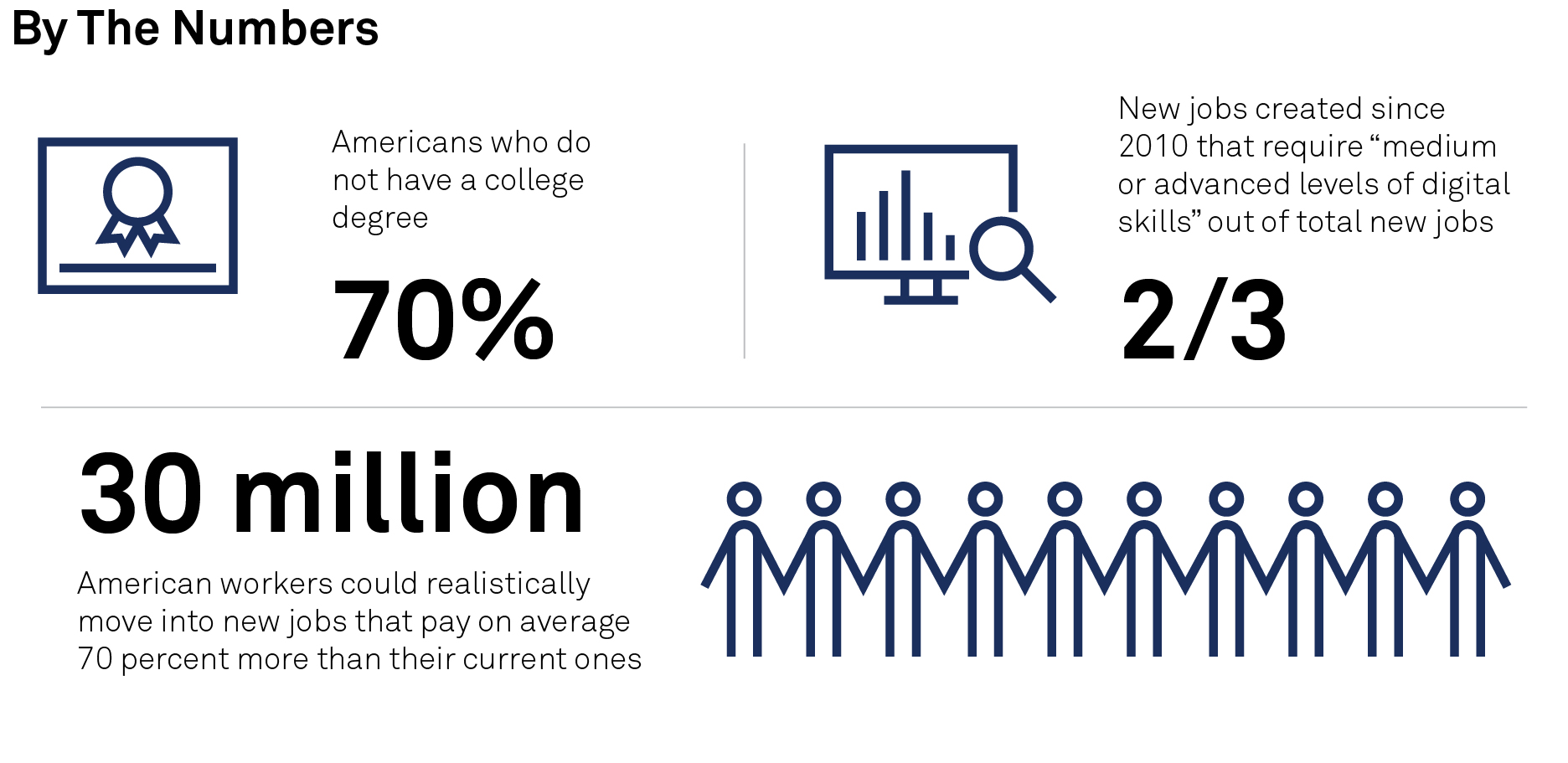

Ensuring that workers have the right skills that qualify them for jobs paying at least middle-class wages, or career paths that promise to do so, is especially important for the almost 70 percent of Americans who do not have a college degree. Although nearly two thirds of new jobs created since 2010 have required “medium or advanced levels of digital skills,” according to the Markle Foundation,[ii] those skills often can be acquired without the time and expense of obtaining new degrees. Peter Blair and his coauthors have estimated the number of workers who are potentially skilled through alternative routes (STARs) – looking at the “skill distance” between a worker’s current occupation and higher occupations with higher wages that have similar skills requirements in their local labor markets [Blair et al]. They argue that as many as 30 million American workers could realistically move into new jobs that pay on average 70 percent more than their current ones. Many of the skills that are required do not require a college degree. Instead, they can be acquired through training and following occupational pathways that permit their accumulation.[iii]

In the technology sector, some companies already have begun offering certificate programs directly, without affiliations with educational institutions, to provide and certify skills for a broad range of workers, primarily not those currently employed at the companies. For example, Google has developed inexpensive training programs that allow workers to identify opportunities and take low cost or free courses that equip them with digital skills in occupations such as IT support, Data Analytics, Website Design, and Project Management. These programs provide enrollees upon completion with “Career certificates” that allow these workers to reliably signal to prospective or current employers that they have certain skills. Amazon has committed to providing free skills to 29 million people worldwide. Similarly, IBM, Microsoft, and Amazon have extensive training programs that develop and certify IT skills that are sometimes provided in conjunction with educational institutions.[iv]

Spurred by a worker shortage in the wake of the COVID pandemic, an even broader range of companies are providing in-house training to enhance skills of their own workers. A June 2020 survey reported 42 percent of companies had stepped up their upskilling/reskilling efforts by that point of the pandemic, with virtually all of them (91 percent) reporting corresponding increases in worker productivity [Apostolopoulos]. In late July 2021, Walmart announced it will cover 100 percent of the cost of attending 10 online universities for all its employees.

Of course, workers who seek to gain new skills through non-traditional means will be most incentivized to do so if firms hire workers with new forms of skills certifications. This requires a mindset shift among employers, who for the most part, have long relied on degrees from recognized educational institutions as a prerequisite for even considering job applicants for employment. Firms are more likely to acquire this new mindset in a “high-pressure economy,” one where tight labor markets compel employers to rethink their hiring criteria. Most famously, this happened during World War II when women – Rosy the Riveters – were hired for factory jobs because the men who used to do them were off fighting the war. Similarly, the great macroeconomist Arthur Okun showed how in the 1960s tight labor markets disproportionately benefitted lower wage workers [Okun]. More recently, Aaronson and her colleagues found similar results when the unemployment rate fell below 4 percent in the final years of the Trump expansion just prior to the Covid pandemic [Aaronson et al].

Many companies are also recognizing the value of hiring and promoting a diverse work force, matching the changing demographics of our country. Later in this report we urge public companies to be more open and transparent about setting these goals, which stakeholders can help enforce. These commitments could incentivize the business community to become even more active in advocating for school reforms and pedagogical changes that narrow current educational achievement gaps by uplifting those of all races and ethnicities who currently and historically have lagged.

Meeting the Challenge of Climate Change: Whatever policy incentives or mandates that governments may adopt to induce the reduction of GHG emissions and ideally concentrations in the atmosphere, the U.S. and the rest of the world will only address climate change through commercialized innovations, which will only be brought to market by private firms and their investors [Gates]. But changes in the behavior of consumers, firms and investors can also contribute.

As in other sectors of the economy, firms and their managements differ on their risk tolerances, especially in pursuing business strategies with primarily, if not only, long-term payoffs, which characterizes the market for innovations combating climate change. Firms willing to take on this risk – innovating climate friendly technologies, following environmentally sound practices and adopting these technologies and practices – are following the advice of hockey legend Wayne Gretzky in skating to where the puck is going, not where it has been. In early August 2021, several major auto manufacturers announced they planned to have 40-50 percent of their U.S. sales comprised of cars powered solely by electricity, hybrid, or fuel cell technology by 2030. Tesla, of course, already has a fully electric fleet. One of the country’s leading electric utilities, Southern Company, reports that it is on target to cut its own GHG emissions by 50 percent by 2030 and to hit net zero emissions by 2050 [Kovaleski].

Apart from announced company-specific climate changes, several major companies – including Alphabet, Apple, Ford Motor, Johnson & Johnson, and Walmart – have endorsed the Biden Administration’s target to reduce GHG emissions by 50 percent by 2030 relative to a 2005 baseline.

Polling data indicate strong support among multiple stakeholders for companies responding to environmental challenges. An IBM survey of 1,400 people in multiple countries finds that more than 70 percent of respondents say they are more likely to work with a company with a good environmental reputation, 55 percent say they are willing to pay a green premium on the goods and services they buy, and 48 percent of investors say their portfolios “already takes environmental sustainability into account.” Another 21 percent say they will likely add sustainability as a factor for future investment decisions [Foster].

With the right information, other corporate stakeholders – especially investors – can also help drive firms to be more climate friendly. Already, nearly half of the public companies represented in the S&P 500 Index now disclose risks to their business, as part of their annual 10-K disclosures, posed by climate change – risks to their “physical” operations and “transition” risks to the value of their assets from climate-induced shifts in demand for some of their products or activities [Bloomberg Law]. But investors are increasingly demanding more, wanting to know not just how climate change is affecting business, but what public companies are doing to combat climate change, as part of a larger trend toward disclosing information enabling third parties to assign them “environmental, social, governance” (ESG) scores. These measures represent composites of scores on companies’ meeting environmental (E), diversity hiring and promotion and employee health and safety (S), and corporate governance (G) goals. Institutional investors have been offering diversified ESG funds or ETFs to meet investor demand for securities issued by companies with high ESG ratings. Bloomberg Professional Services estimated in 2020 that $40 trillion in global assets were managed by entities that factor ESG data into their investment strategies. BPS projected that within the next five years, 50 percent of all professionally managed assets will consist of ESG-mandated assets [Bloomberg Professional Services].

In April 2021, the European Union issued a far-reaching proposal that would require banks and a broad range of institutional investors to meet a wide range of ESG requirements, which would apply to all funds, even if they do not market themselves as “sustainable” or with the ESG label.[v] At the time of writing, the SEC is expected to issue in fall of 2021 ESG disclosure rules for public companies in the U.S.

Given the extraordinarily large and growing number of providers of ESG ratings and the different ESG scoring methodologies they use, there is a clear need for standardizing ESG disclosures. Toward that end, multiple international organizations have issued ESG standards or are working on them [U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation; D’Aquila]. But so far there is no single accepted body of standards analogous to the financial reporting standards issued and maintained by the Financial Accounting Standards Board. It may turn out that a single set of standards ultimately will be produced and accepted globally.

One additional effort should be made in this regard. ESG ratings are composite weighted averages of the scores of each of the components, namely the E, S, and G. Some companies and ratings agencies currently provide disclosures of each of these components. But investors would benefit not only from universal disclosures of these components, but also from standardized disclosures of each of these elements, how they are calculated, and the weights used to arrive at any composite score.

The complexities involved in the scoring of companies’ carbon or GHG “footprints,” a key component of the overall ESG score, nonetheless have not deterred efforts by some companies to buy carbon offsets encouraging innovative ways of reducing or withdrawing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The Cool Effects profile in the accompanying Profiles in Entrepreneurial Leadership describes the emergence of one voluntary carbon market in which offsets are created through multiples means – such as emissions reductions by manufacturers, replacement of fossil fuels with renewables, and payment to timber owners not to cut trees [Dezember] – which are then traded. Voluntary carbon offset markets will be effective in cost-effectively reducing GHG emissions, only if the offsets can be accurately quantified against a baseline of what would have happened in the absence of the emissions reduction effort and verified in a trustworthy way – challenges that are widely recognized but that have not been resolved.

Overcoming Systemic Racism: Many companies have long been active in trying to hire and promote Blacks and other disadvantaged minorities. For example, many companies have worked with the Minority Business Council for years to increase procurements from minority owned suppliers. Most major corporations have had diversity programs of some sort for years. In 2012, more than 50 major corporations backed affirmative action in an amicus brief submitted to the Supreme Court in Fisher v. University of Texas, because the companies expressed a need for diversity in their workforces [Wilson].

Yet despite enhanced efforts by businesses in recent years to hire and promote Blacks and women, members of both groups still account for a disproportionately low percentage of corporate executives, especially Black women. Only one Black woman CEO is on Fortune’s 500 List, and there are currently only two Black men. Black women make up 7.4 percent of the US population, but only 1.6 percent serve in Vice Presidential roles and just 1.4 percent in executive positions in US corporations. While White women hold 32 percent of all management positions, Black women hold a mere 4 percent. The low percentages for Black women have held consistent for decades. [Bell and Nkomo].

One of the reasons for these low percentages is that it is not enough for companies to mentor minority candidates for promotion: they need to provide sponsors who will advocate for qualified candidates for leadership roles. [Hewlett]. Black employees must be in leadership positions that substantially contribute to a company’s success. Sponsors help to create this reality.

Minority entrepreneurs also still face daunting challenges, not only in attracting capital, but in tapping into networks for talent and mentorship. Minorites also grow up in families with less wealth and are less likely to have parents or a close relative as an entrepreneurial role model. These barriers are especially high for minority women [Menon].

The murder of George Floyd and the outpouring of diverse public support spurred an expansion of corporate efforts in this area. Since the summer of 2020, the nation’s 1,000 largest companies have pledged $66 billion in total contributions to racial justice causes. The Business Roundtable companies have pledged efforts to close the racial opportunity gap through policy changes in employment, housing, finance, education, health, and criminal justice [Liu and Dinkins].

Several additional specific corporate efforts are worth highlighting:

There is broad corporate support, 37 major companies in all, for OneTen (oneten.org) a new organization formed to develop ways that businesses and educational institutions will hire, train, and retain diverse individuals, with explicit commitments to hire and promote Black Americans without four- year college degrees.

The NinetytoZero alliance of several major companies, consulting firms, academic institutions and non-profits is committed to undertaking multiple concrete actions to help close the Black-White wealth gap. The alliance has developed goals for hiring Black talent, spending money with Black-owned businesses, investing with Black-owned or led asset management companies, building efforts to promote inclusion into accountability for corporate executives (more on this later in the essay), improving access to asset building tools for Black employees, and establishing business relationships Black-owned financial institutions.

The NBA has committed to a broad effort to do business with suppliers owned by minorities, women, LGBTQ individuals and veterans and work with agencies that certify these suppliers. During the COVID pandemic, many owners of NBA teams have been joined by some owners of baseball, football, and hockey teams to open their arenas as places for voting in the 2020 election.

Corporate America has come a long way since the days when it was “courageous” for Robert Woodruff, the retired CEO of Coke Cola, to use his influence with Robert Austin, the then current CEO of Coke, to convince the company and other Atlanta businesses to participate in a celebratory dinner to honor Martin Luther King after he won the Nobel Prize [Burress]. Or even earlier when it was courageous for Branch Rickey, then general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, to have brought Jackie Robinson to Major League Baseball. More such courage is still required today, and we later outline how corporate American can help meet that challenge.

Reinvigorating Democracy: Democracy depends on an engaged and informed citizenry. One of the major challenges of our digital era is to maximize the availability and absorption of truthful information regarding events that relate to public policies – such as the science of diseases or climate change – relative to false or misleading information about these matters.

As we write this, and we suspect for a good while longer thereafter, citizens and policy makers will be debating what to do about this problem. Much of the debate, so far, has focused on changing in some manner Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which immunizes providers and users of a “interactive computer service” – a social media platform, for example – from legal liability for content posted by third parties. As it is now, Twitter and other digital platforms are not treated as “publishers,” who can be subject to liability for defamatory content, by statute.

We do not take a position on any of the various Section 230 reforms that have been proposed because we do not have feel confident in predicting both their intended and unintended consequences. But one thing we can state with confidence is that vesting any government agency with the power to censor or fine the platforms is not the answer to the divisiveness caused by social media. Giving government that power would be so clearly inconsistent with the First Amendment, which prohibits only government actions that limit free speech, not those of private parties.

There is one more positive, and unfortunately politically controversial, area where government can help sustain democracy – where many in the corporate community have recognized it is in their interest and that of our country. That area is to remove barriers to voting that would disenfranchise legal voters, and to ensure the partisan-free integrity of the counting of votes, since voting is the most basic element of democracy. On April 14, 2021, over 300 corporate leaders signed off on statement published in the New York Times and The Wall Street Journal “defend[ing] the right to vote and oppose any discriminatory legislation.” This statement followed an earlier statement published in the New York Times on March 31, 2021, created by the Black Economic Alliance, comprising 72 of the most prominent Black corporate executives in America, calling on corporate America to respond boldly to new state legislative initiatives, all prompted by the false claim of substantial voter fraud in the 2020 elections.

Corporations now have the legal right to use their voices on matters of the day thanks to the Supreme Court in Citizens United, which held explicitly that corporations have free speech rights under the First Amendment. Corporations are increasingly recognizing that without a functioning democracy, capitalism itself is under threat. This is a welcome development and should not be surprising.

As much as corporations can do to help advance important social objectives, for several reasons they alone cannot solve all of society’s challenges.

First, when government policies fail to ensure that private companies fully internalize all social costs (or benefits) from their activities, such as emitting GHGs, then corporations will have limited, if any, incentives to tackle social problems unless they can at least see a long-run financial benefit from doing so.

Second, it can be difficult discerning the true sentiment of multiple stakeholder groups and its intensity – namely, whether and to what extent corporate stances and actions affect the sale of the company’s goods and services and its ability to attract and retain talented workers and executives.

Third, corporations must decide which of many issues to engage with, realizing not only competing views on these subjects within their stakeholder groups but also that whatever stances they may take may not benefit all these stakeholder groups. For example, should a U.S.-based company that stands up for voting rights in the U.S. do the same for political rights of citizens of other countries in which they do business? Or how to account for the reality that choosing not to business in a jurisdiction can hurt local customers and suppliers there?

[i] The cities were Charlotte, Cleveland, Houston, Indianapolis, Memphis, Rochester, St. Louis, and Seattle. The surveys were conducted by YouGov in January and February 2018 and are representative samples of the adult population of each MSA.

[ii] Markle oversees Rework America an initiative to connect workers to middle-skill jobs see https://www.markle.org/rework-america/

[iii] See the job progression tool developed by McKinsey & Co that allows job coaches and career navigators to consider how employment options can advance economic opportunities based on data on four million job transitions. https://www.mckinsey.com/about-us/covid-response-center/response-tools/for-governments/job-progressions?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hdpid=0e321773-d484-4301-bddb-8e42c18ce2e2&hctky=1345299&hlkid=197a5244246f443696f85eab2398461e

[iv] See, e.g. IBM https://www.exitcertified.com/it-training/ibm?tab=training&gclsrc=aw.ds&&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIjbjlybKN8QIV9QmICR1dpgi3EAAYAiAAEgLHuvD_BwE and Amazon https://aws.amazon.com/training/ https://docs and Microsoft microsoft.com/en-us/learn/certifications/

[v] https://frv.kpmg.us/reference-library/2021/european-esg-reporting-directive.html.