Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Highlights

Sharp but short? Extended coronavirus-containment measures are pushing the world into the deepest recession since the Great Depression. Although we expect the drop in economic activity to be sharp but fairly short, the path to recovery remains very uncertain in its timing and trajectory, until an effective treatment or vaccine are in place.

Corporates take largest hit. Corporate credits were first hit by the sudden stop in economic activities and the collapse in oil prices, with a disproportionate effect on credits at the lower end of the rating scale and in the most exposed industries. As we entered the crisis with a record level of credits rated ‘B’ and below, this will likely push the speculative-grade default rate above 10%.

Banks and structured finance aren’t immune. Banks entered the crisis with strong balance sheets and are generally expected to show resilience, but they aren’t immune to the longerterm economic implications. Ratings effects on securitization will reflect the trend in underlying assets.

Emerging markets facing a severe shock. Domestic measures to contain the rapid spread of the pandemic and the impact of extended developed-economy lockdowns on trade and tourism, compounded with the collapse in oil price, have pushed many emerging markets into recession. Risk aversion triggered unprecedented capital outflows, tightened financing conditions and pressured currencies. With external risks remaining on the downside, some countries are better positioned than others to cope with burgeoning pressures.

Policy choices matter. Unprecedented fiscal and monetary support are critical to preserve the economic fabric and well-functioning capital markets, thereby supporting the chances of a stronger path to recovery. But it comes at the expense of higher government debt and puts the onus on policy choices in the handling of the health issue, the degree and nature of support to the economy, and, later, the exit path—all of which will have a significant impact on the recovery trajectory.

Government measures to stem the spread of coronavirus have escalated in the past three weeks amid a tripling of confirmed cases globally, to more than 2.5 million. These measures, together with business and consumer behavioral changes, are resulting in wider and deeper economic effects— and worse credit conditions—than we estimated our previous report, “Global Credit Conditions: Triple Trouble: Virus, Oil, Volatility,” published April 1. We also see the post-pandemic recovery taking longer, based on the experience of China, the first major economy to emerge from the crisis.

As a result, both the first-order effect on corporate ratings and second-order effects on banks, securitization ratings are likely be more negative than initially anticipated, particularly at the lower end of the ratings scale. Although unprecedented measures from governments and central banks are mitigating the effects of the vertiginous drop in activity in the second quarter and partially addressing market liquidity risks, the path to recovery remains very uncertain both in terms of timing and trajectory. It comes at the expense of higher government debt and puts a lot of weight on policy choices in the handling of the health issue, the degree and nature of support to the local economy, and, later, the exit path—all of which will have a significant impact on the recovery trajectory.

S&P Global Ratings lowered its economic forecasts for 2020 to reflect the extension of lockdowns in major economies in Europe and the U.S., and the prospects for a slower recovery (see “COVID-19 Deals A Larger, Longer Hit To Global GDP,” published April 16). We now expect global GDP to shrink 2.3% this year, far worse than our March estimate of 0.4% growth. We now anticipate contractions in the U.S. and Eurozone of 5.2% and 7.5%, respectively compared to -1.3% and -2% in our previous forecast (see chart 1). Asia-Pacific will grow just 0.3%, down from 2.2% in our previous forecast. We also lowered our estimate for emerging markets to reflect the direct effects of the pandemic on local economies and indirect drag through the drop in tourism and disruption in supply chains.

Except for China, which suffered most in the first quarter, many major economies would be hit worst in April-June. We anticipate the recovery through the second half of the year to be slow before gathering strength into 2021. However, the resulting 5.8% global growth rate we see in 2021, driven by a rebound of demand, would be insufficient to recover lost output.

Our current base case uses estimates from government authorities that the pandemic will peak around midyear, with lockdown measures in place until May in the largest global economies, and a gradual lifting and reopening of economic activities in stages through the third quarter as consumer demand revives and firms rehire workers, fill back orders, and restock inventories. Early evidence from China is that the return to pre-crisis levels of activities is very gradual, particularly for services sectors (leisure, retails, travel, hospitality, gaming, etc.) more hit by social-distancing measures than manufacturing activities are. Until an effective treatment or vaccine is in place, significant uncertainties surrounding the resolution of the pandemic. Possible multiple waves of infection might lead to on/off lockdowns. Any prolongation in containment measures or return to lockdowns could result in a disproportionate hit to the economic and credit risks, threatening employment and the survival of a large number of companies. A drawn-out crisis might also reignite asset-price swings and funding pressures, particularly for more vulnerable speculative-grade issuers already facing constrained access to finance.

In addition to the uncertainty on the timing of recovery, until a vaccine is found, the level and path of economic growth in a post-coronavirus world is subject to lots of uncertainties. The potential damage to the fabric of the economy relating to employment, capital, and productivity will be a key determinant. Changes in consumer habits affecting demand in certain industries, potential acceleration in secular trends, and disruption to global supply chains could also shape the landscape of industry performance heading into next year. Overall, policy choices will be important determinants of the health and economic crises at the national level, and the exit path from these extraordinary measures will also weigh on the longer-term recovery.

Reflecting these uncertainties, S&P Global Ratings’ Credit Conditions Committee is revising to ‘very high’ from ‘high’ the risk that global conditions might worsen even beyond this new base case.

In this period of high uncertainty, S&P Global Ratings is striving to provide the maximum transparency to our rating approach and help the market participants understand how we reflect our base case assumptions and downside risks into our ratings.

There are several key differences between the current situation and the Global Financial Crisis (and previous recessions) that are worth keeping in mind when assessing of the credit implications of this downturn.

– Sharp but short: While this global recession will likely be the most severe since the Great Depression, we also expect it to be exceptionally short due to its nature: the drop in GDP comes from a sudden stop in economic activities as countries shut down. But the decline should be mostly concentrated in a quarter or two, with a sharp rebound in activity as containment measures are gradually lifted.

– Corporates first: Again unlike the GFC, the corporate sector is suffering first this time, with certain industries choked by a brutal interruption of their activities. And this sudden stop is forcing corporates to increase debt levels to survive as recession hits, rather than focus on deleveraging that would be more typical in a normal cyclical downturn. Among corporates, services sectors, rather than manufacturing, have been hit harder by social-distancing measures as reflected in purchasing managers indices. The historic collapse in oil prices is amplifying the effect on corporates. The banking sector, securitizations, and sovereigns won’t be immune to these negative developments, but many will suffer second-order effects.

– Fasten your seatbelts: The pace of deterioration this time has been a lot faster than in any previous crisis. After a record run of benign economic and credit conditions since the GFC, the wake-up call has been brutal.

– Belt and braces: The last key difference in this crisis is the unprecedented fiscal and monetary support provided by the largest governments and central banks very early on, learning from the GFC the importance of the timeliness and size of support. This stimulus is critical to ease the pain of the sudden drop in economic activity on employment and preserve the economic fabric, in particular for small and midsize enterprises (SMEs). It has also proved instrumental in restoring confidence in the capital markets and bringing back the role of markets in financing the economy, although a blind spot might remain for highly leveraged companies.

Although our economic forecasts continue to worsen, financing conditions have been gradually improving, particularly after the U.S. Federal Reserve’s historic liquidity facilities, introduced on March 23, and expanded on April 9. Other central banks and governments have enacted liquidity measures, too, notably the European Central Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP). However, the response in primary bond markets to the Fed’s actions remains the most substantial, even in Europe, as the dollar has started to fall in value nearer to exchange rates seen prior to the virus’s outbreak in the U.S. Meanwhile, the lifting of some social-distancing measures in China, alongside central bank support, appears to be improving lending trends there, pushing March corporate bond issuance to an all-time monthly high.

Still, we see more-restrictive lending conditions amid the material contraction in economic activity from global containment measures. Thus far, borrowers with stronger credit quality have been able to largely resume issuing debt, while funding costs remain prohibitively high for weaker borrowers in an environment of collapsing revenues

Support measures by central banks and governments have helped stabilize financial markets; however, these actions aren’t a cure-all. Financial markets have also been taking heart from the pace of new COVID-19 cases slowing in many countries. That said, the fundamental headwind of the virus and the necessary containment measures are still present. And while the pace of new cases appears to be moderating in most of the developed world, nascent signs of resurgence are appearing in China and northern Japan. Moreover, many emerging markets are less-equipped to contain the virus and treat the ill, which could exacerbate or lengthen their suffering.

For now, markets are still reflecting heightened stress relative to the start of the year, but less than around mid-March. Though tempting to take recent investment-grade global bond issuance as a signal that markets have turned a corner, the record haul since the last week of March may be more of a pull-forward of future issuance than a new normal. More than likely the firms that have come to market have done so to secure cash at favorable yields during the Fed’s honeymoon period to get ahead of what will undoubtedly be dismal earnings seasons in April and July.

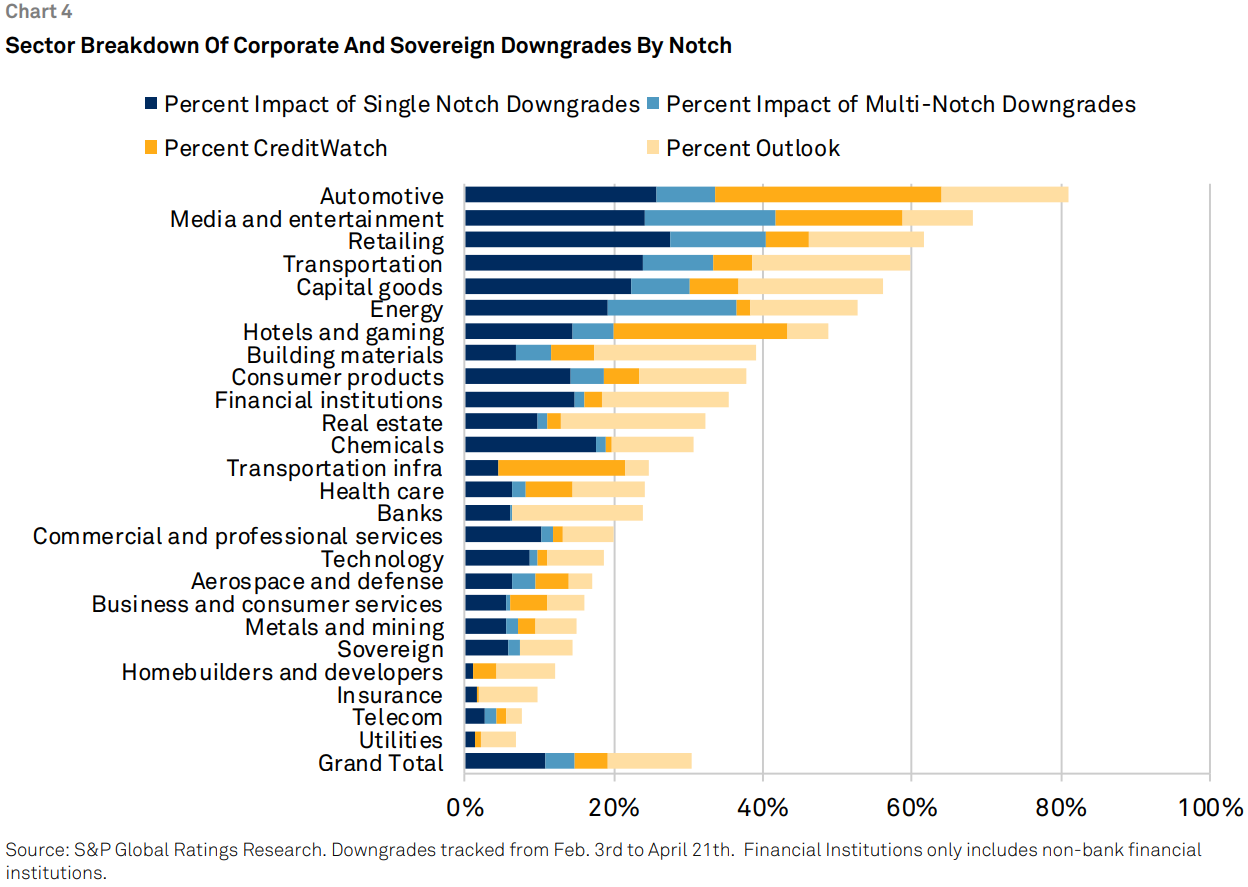

Corporate borrowers have been the first hit by the sudden stop in economic activities and the collapse in oil prices. But the severity varies significantly by industry and rating level. To take the full measure of the implications on corporate ratings, it’s important to look at the evolution of the ratings landscape in the past 10 years. A decade of accommodative monetary conditions, with low interest rates and abundant liquidity, fueled smaller and more highly leveraged companies to tap capital markets and take on moreaggressive financial policies. This resulted in a significant increase of debt issued by companies with speculative-grade ratings (see chart 2).

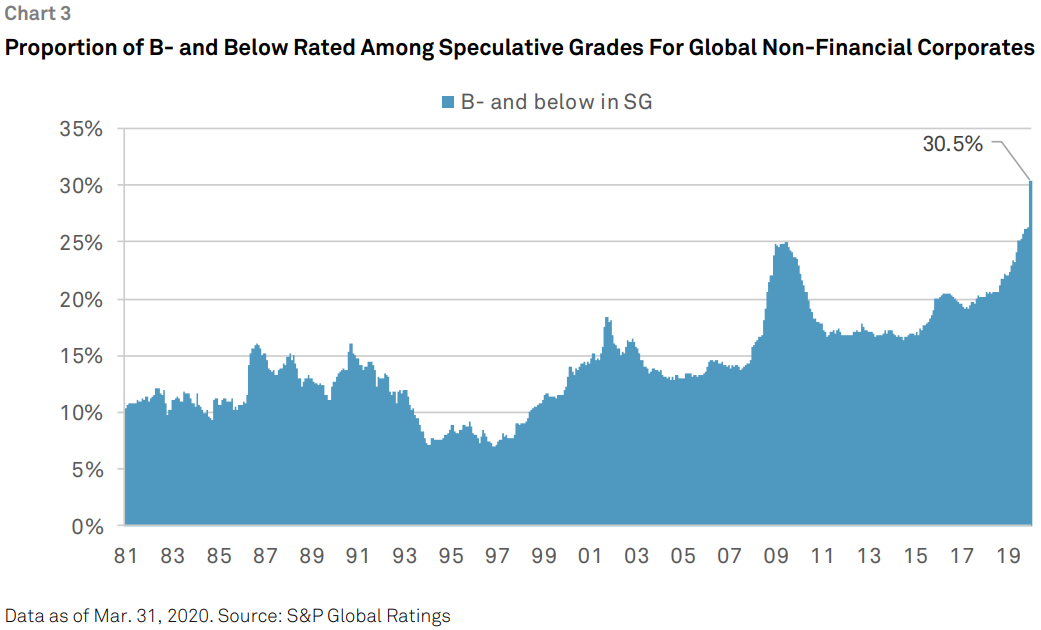

More specifically, in the 2-3 years leading up to the current crisis, a record number of companies came to market with first-time ratings in the ‘B’ category (which includes ‘B-’ and ‘B+’). In parallel, companies across a range of sectors have added leverage and adopted more aggressive financial policies—and some were already starting to experience pressure from the slowdown in global growth. As a result of both new ‘B’ ratings and credit quality transitioning lower, we entered this downturn with median ratings at the lowest in the past decade in a large number of industries, and with a record number of corporates in the ‘B’ category or below (30% of spec-grade ratings in the U.S. and 20% in Europe, see chart 3).

This landscape has many implications for the expected ratings transition among corporates, as these ratings levels indicate a high vulnerability to changes in economic and financial conditions. These companies are also the least-supported by fiscal and monetary measures across geographies.

In any deep recession or credit crunch, the effect on ratings is more pronounced at the lower end of the credit spectrum, because lower-rated issuers generally have weaker business characteristics and higher leverage entering the crisis, and less financial flexibility and shallower liquidity to cushion the blow. Companies rated in the ‘B’ and ‘CCC’ categories, depending on their sectors face an existential crisis, as they may not have the resources to navigate through the downturn. As we move to the ‘BB’ category, we see less ratings volatility, but still a wide range of downgrades as companies are in a more vulnerable position until the recovery emerges. Investment-grade credits have deeper liquidity sources and ability to weather extremely weak credit conditions. There still have been downgrades on investment-grade companies, and this will likely continue in the near term, but generally these actions have been less frequent and less severe.

We also believe that the shape of the recovery will differ significantly by industry, depending on the exposure to ongoing forms of social distancing and other key factors. Below are examples of sectors where we have weaker key assumptions for next year and potentially beyond:

– Traditional retailers, retail real estate, movie theater owners. These sectors were already undergoing long-term secular pressures reducing demand, and the pandemic may accelerate these trends. In addition, office-real-estate owners were already seeing slight pressure as companies reduced their size of offices, and this may accelerate.

– Airlines, hotels. Sectors tied to long-haul or business travel may take much longer to recapture revenues from before the crisis.

– Autos, discretionary consumer goods. Large, discretionary purchases could remain weaker for longer due to higher unemployment levels.

– Midstream, oil services. The severe collapse in commodity prices could have a protracted effect on certain sectors due to the lag of upcoming bankruptcies and potential liquidations in the oil sector.

Central banks’ unprecedented and wide-ranging monetary actions have largely delivered upon their primary objective to reduce market volatility, reopen primary markets, and stimulate liquidity. Investment-grade issuance in the U.S. and Europe surged as borrowers took advantage of conditions to bolster liquidity, and institutional investors re-emerged, attracted by elevated yields and new-issue premiums.

The reopening of speculative-grade markets has been slower and more uneven. U.S. spec-grade bond markets have picked up, with year-to-date issuance of $25.2 billion as of (April 21)—including $8 billion from fallen angel, Ford Motor Co. However, Europe’s spec-grade bond, and leveragedloan markets in both regions, remain largely shuttered, bringing the primary funding freeze to a record eight weeks.

How long speculative-grade issuers can sit out intentionally (unwilling to accept structure or price) or unintentionally (lack of investor appetite) is unknown and inevitably varies across issuers and sectors. In the meantime, these issuers have tapped credit facilities (drawing $84 billion, according to public SEC filings). Some have addressed liquidity needs via other sources of short-term funding (364-day term loans, upsize revolvers). Additionally they may seek, or have sought, to access central bank programs and government guarantee plans in place to support small and mediumsized businesses, depending on their eligibility.

Some more-stressed privately owned companies have benefited from equity contributed by their financial sponsors toward the entity’s more critical liquidity needs.

The longer the primary funding markets remain shuttered, the more perilous conditions will become for speculative-grade borrowers. In particular, the timeline for the meaningful reemergence of loan financing markets looks uncertain while pricing remains elevated, loan fund inflows remain light, spec-grade default look set to rise, and one of the largest investor classes— CLO funds, which account for about 60% of primary loan issuance—largely remain on the sidelines.

Speculative-grade issuers today represent a larger percentage of our corporate ratings than during the GFC, and while issuers are generally able to drawn down existing facilities (not necessarily the case during the GFC), the duration and source of available liquidity remains a key focus for us while primary funding markets remain largely shuttered.

The deterioration of ratings on corporate loan borrowers has repercussion in the ratings mix of obligors found within U.S. CLO collateral pools. In the space of less than two months, since early March, U.S. CLOs have seen their average collateral credit quality drop by more than a notch, to ‘B’ from ‘B+’, and their average ‘CCC’ bucket increase to nearly 12% from about 4%. These changes are pressuring CLO ratings, especially for lower-mezzanine and subordinate tranches. For U.S. CLOs, stress scenarios we have generated across our rated book suggest that even under dire circumstances, ‘AAA’ rated CLO notes are well-protected and can withstand upward of 60% of their collateral loans defaulting, at an average recovery rate of less than 45%, without suffering a loss. Under more plausible—but still harsh—stress, a large majority of senior U.S. CLO notes would maintain their ratings, while tranches rated ‘BBB’ and lower would bear the brunt of the downgrades and defaults.

European CLOs have seen less collateral deterioration. Applying a variety of stress scenarios to a typical European CLO transaction shows that the rating changes, if any, would generally be greater further down the capital structure. In 10 scenarios of varying severity, the 'AAA' tranche rating appears resilient, and the 'BBB' rated tranche remains investment-grade in most cases. However, in the most severe scenarios—in which all underlying obligors are downgraded, or 10% of them default—CLO ratings throughout the capital structure could fall 1-3 notches.

This analysis may be broadly representative of how our European CLO ratings could move in certain downturn scenarios, but in reality the ratings migration would differ among transactions, depending on structure, portfolio, and manager. Since mid-March, the increased exposure to assets rated in the 'CCC' category continued at a faster pace, going from an average 3% to just below 9% in April. At the same time the average percentage of ‘B-’ asset has increased minimally, being still under the 20% mark. Nevertheless, the average level of non-performing assets in European CLOs is less than 0.15% as of April.

After a decade of tighter regulations around the world, banks are entering this crisis with much stronger balance sheets than they had at the onset of the GFC. Capital and liquidity levels will provide material buffers for large banks in advanced economies to cushion the blow from this downturn. This enables them to act as a conduit for economic and monetary policies aiming to reduce the immediate effects of the economic stop. Public authorities have implemented a broad array of measures to incentivize banks to continue lending and show flexibility toward struggling customers. In return, banking systems are receiving substantial liquidity support, and regulations are being relaxed temporarily. Nevertheless, some banking systems will have less latitude to provide support.

Either way, banks around the world will this year face negative ratings momentum as a result of the significant effects of the pandemic, oil-price shock, and market volatility. We anticipate this will mostly be limited to negative outlook revisions thanks to some of these supporting factors. Underpinning our expectation of a more negative outlook bias, banks' creditworthiness ultimately remains a function of the economies they serve. Our expectation for a strong rebound in most markets next year suggests that short-term forbearance at this stage may limit credit losses later. But the long-term stresses many customers will experience will, over time, flow through to banks’ profit-and-loss statements.

Also, once the dust settles and economies bounce back, the earnings recovery for banks is unlikely to be as sharp as the GDP rebound. Many banks will face customers that may be prone to deleverage, a cost of risk that will likely be well above pre-pandemic levels, and the prospect of lower rates for even longer. All of this will likely weigh on earnings that were already feeble in some regions at the onset of the crisis. They will also force many banks to undertake a further round of structural measures to address chronic performance issues.

We will monitor the long-term effect of the current relaxation of various bank regulations, for instance in terms of capital buffers and forbearance. The effects in the next few months are likely to be positive for banks, enabling them to maneuver through the worst of the crisis, in line with the original intentions of these regulations. But it’s still too early to predict whether some of these changes could become more permanent. If so, a long-term term weakening in banks’ capital and liquidity targets, or less transparency in recognizing bad debt and delays in adequately provisioning for it, could lead to persistently weaker balance sheets and erode investor confidence. The weakening capitalization of banks could affect a number of ratings, both in developed and emerging markets.

In determining which bank ratings could suffer most, we take into account the headroom within individual ratings for some deterioration in credit metrics, as well as relative exposure to the most vulnerable sectors and customers. We also consider the relative effectiveness of banks’ public authorities in curbing the credit effects on customers and supporting a rapid rebound once the situation abates. Finally, we also take into account how sovereign support influences ratings, and how subsidiaries fare in the context of group-rating considerations.

Concentration risk to single-name exposures, and particular industries or regions, may exacerbate banks’ sensitivity to deteriorating operating conditions. Stresses could also lead to a “flight to quality.” We therefore anticipate that, in certain markets, we may see a greater divergence in the credit profiles of larger, more diversified banks compared with more regional, or specialized, players.

Insurers with thinner capital buffers and those more exposed to financial-market volatility have accounted for the majority of the negative rating actions in the past 2 months. In aggregate, we continue to expect insurance claims to be manageable and future downside pressure will stem from a prolonged macro-economic recovery, even lower for even longer interest rates, outsized exposures to spec-grade and ‘BBB’ rated bonds and any further financial market deterioration.

Through this period we have seen financing conditions remain relatively attractive for insurers. We believe that there are no widespread, underlying credit issues behind many decisions across the insurance sector to suspend the payment of dividends in the first part of this year.

That said, second-order downside risks are apparent, given insurers’ roles as investors and interlinkages with upcoming deterioration in other asset classes. Rating actions will be targeted and not widespread but a product of the combined pressures from investment exposures, gradual capital and earnings erosion, as well business model and expense pressures due to lower sales. Capital is king and, combined with future management decisions to help rebuild capital buffers, will be the best defence against the pressures over the next 12-18 months.

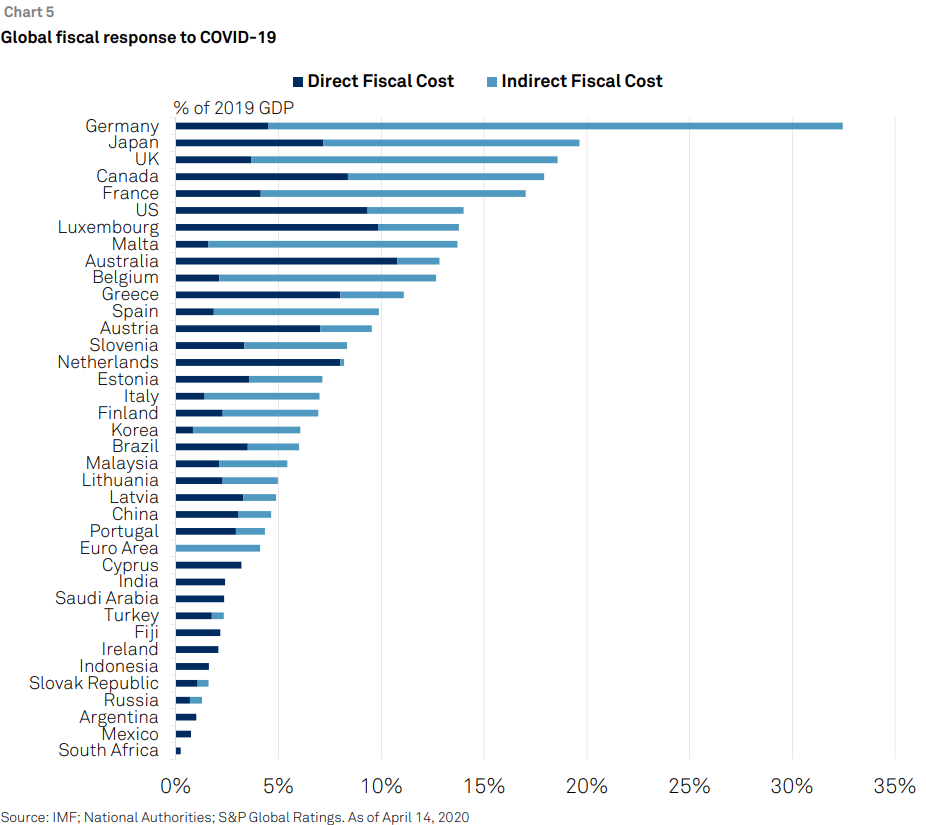

The unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus that many sovereigns are implementing in order to help their economies weather the pandemic will have long-lasting consequences. These stimuli will add large amounts of sovereign debt to a stock that already was massive.

In January, we expected sovereigns would collectively borrow around $8.1 trillion to cover financing needs. We now expect another $4 trillion will be added—with the distribution of issuers remaining more or less the same as before the pandemic.

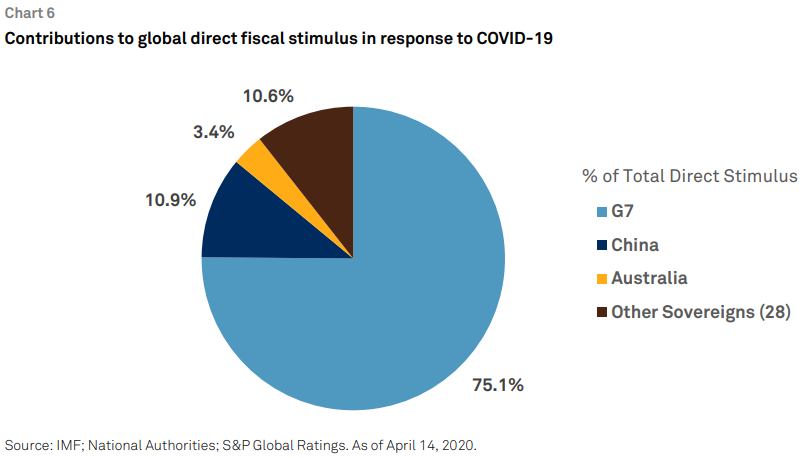

Of the 37 countries that announced actual direct fiscal spending, those in the G-7 account for 75% of the total; China makes up 11%; the remaining 24% is distributed among 29 sovereigns. Hence, the distribution will more or less mirror that of after the Global Financial Crisis with the Fed, ECB, Bank of England and Bank of Japan holding large amounts of this debt on their balance sheets.

Considering the state of the global economy and the time it may take for markets to recover, we are likely in an environment of “low for much longer” interest rates.

Our sovereign ratings before the pandemic already reflected some of the weaknesses associated with the debt-buildup governments around the world had to do to cope with the effects of the GFC. Several sovereigns lost their ‘AAA’ rating, and many others fell out of investment-grade. At the start of the year, about 80% of sovereign debt we rate was below 2008 levels. Italy, for example, was at ‘A+’ before the Eurozone debt crisis, and since 2011, its rating has fallen four notches, to ‘BBB’ with a negative outlook. The U.S., France, Spain, and the U.K. were all ‘AAA’ before the GFC, and all are now from one notch lower (e.g., the U.S. which is at ‘AA+’)to five notches lower,(as with Spain, at ‘A’).

The question for higher-rated sovereigns is whether they can digest bigger debt levels and other effects of the pandemic. The risk is that some of the consequences will become structural. For example, if the economic recovery takes longer, and larger deficits are needed for a prolonged period—combined with low growth rates—could pressure ratings.

Some spec-grade countries and those at the low end of investment-grade, have already seen several ratings actions in the past three weeks, reflecting our view that some of the consequences and risks of the pandemic for these sovereigns are likely to have long-term effects. We downgraded Mexico’s rating to ‘BBB’ with a negative outlook, and assigned negative outlooks to Indonesia’s ‘BBB’ rating and Colombia’s ‘BBB-‘. At the lower end of the ratings spectrum, there have been two defaults: Ecuador and Argentina recently announced that they would miss payments and would seek debt-restructuring. In addition, several low-income nations in Africa are seeking debt moratoria.

Given our most recent global economic forecasts, we expect continued weakening in structured finance collateral performance. Further, our ratings outlook is stable-to-negative or negative for many asset classes (see table below). We continue to expect the bulk of negative rating actions to hit speculative-grade securities, with some pockets of negative investment-grade ratings activity.

Given the short-term weakness in the macro environment, especially during the second quarter, the risk of increased delinquencies in any specific asset pool has increased across structured finance. Therefore, structural features such as reserve accounts, servicer advancing, excess spread, deferrable bonds/notes, when at least one of these features is present in many structured finance transactions/sectors, will help to mitigate temporary cash-flow interruptions.

If there is a longer-than-expected economic disruption, this would naturally introduce increased liquidity and credit stress. Thus, risks remain to the downside, especially if economic forecasts worsen. Current areas of focus include CLOs, whole business ABS, small business ABS, aircraft ABS, subprime auto ABS, auto dealer floorplan ABS, CMBS with high exposure to retail and lodging, non-QM RMBS and certain sectors in Latin American SF.

While credit markets have stabilized somewhat, commodities markets—in particular the U.S. oil market—have seen historic volatility. Notably, the benchmark price for crude in the U.S. tumbled more than 300% on April 20, to -$37.63—the first time it has ever gone into negative territory.

While the drop in West Texas Intermediate crude was unsurprising directionally—given the imminent expiration of May futures contracts, which created a glut of sellers and almost no buyers—the degree of the decline was obviously historic. It’s common to see volatile price swings in the futures market around contract expiration dates (although clearly nothing like what happened), and such swings are rarely an accurate reflection of longer-term supply-demand fundamentals. A more accurate gauge is the forward curve, which is in a steep contango (that is, futures prices are far higher than the spot price), suggesting investors are optimistic about an eventual recovery in fundamentals and that what happened was an anomaly.

We expect price swings in the near term contracts as high inventory wreaks havoc on prices and creates market dislocations. Still, OPEC production cuts and a likely rebound in demand should improve inventory levels and reduce volatility.

As the pandemic spreads rapidly in emerging markets, social-distancing measures, combined with extended lockdowns in developed economies, are deepening the economic shock. Risks remain firmly on the downside; longer lockdowns could severely hurt household income, corporate liquidity, and banks’ asset quality.

The risk of policy mistakes is on the rise: Failure to contain the pandemic could lead to longer lockdowns and a deeper economic slump. Moreover, the absence of proper economic stimulus could derail recovery and extend the downturn. Most emerging markets have limited room to maneuver in light of weak per-capita income, fiscal rigidities, high or rising leverage, in some cases, and, in a few countries, dependence in external financing. In this context, governments will need to decide which fiscal and monetary policies to implement. At the same time, as cases of the virus rise, policymakers will need to make decisions about lockdowns and how long they last. With very few exceptions, most emerging market economies’ health systems are ill-equipped, with insufficient personal to handle a pandemic.

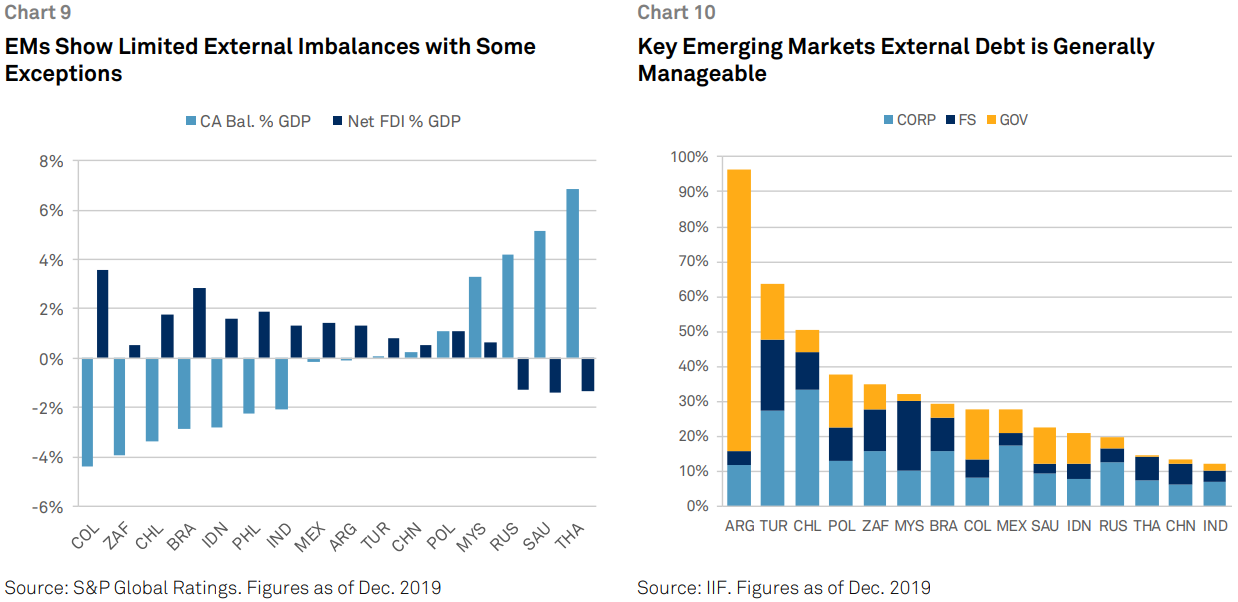

In recent months, emerging markets have suffered unprecedented capital outflows, triggered by risk aversion. Still, emerging markets aren’t facing a generalized balance-of-payments crisis. Overall, key emerging markets had manageable current-account deficits ahead of the crisis, mostly financed with foreign direct investment and moderate foreign currency debt. There were only few cases that were vulnerable to an external shocks (Argentina and Turkey). There are other cases, which external vulnerabilities increased as a result of falling oil prices and decreasing non-oil exports resulting from falling global demand (Colombia and Indonesia). An additional source of external vulnerability is the foreign participation in local currency government bonds, which is relevant in many key emerging markets, including Indonesia, South Africa, Russia, Mexico, Malaysia, Colombia, and Poland. Heightened risk-aversion could trigger a quick exit from these assets, causing additional pressure over interest rates and currencies.

External risks remain on the downside if lockouts in both emerging markets and developed economies persist, causing a deeper recession; this could result in a more severe drag on corporates’ liquidity, mounting risk-aversion, and a second round of capital outflows.

The coronavirus pandemic illustrates the materiality of environmental and social risk factors, along with the importance of strong governance. Since the beginning of the outbreak, health and safety considerations, which we view as a social factor, have guided many business decisions that have potential financial and reputational consequences. Disruptions in operations, supply chains, policy responses, and customer behavior are having, and will continue to have, financial consequences, while damage to a company’s reputation could stem from changes in what is perceived as socially acceptable by stakeholders.

For example, some construction companies have come under scrutiny for requesting employees to commute to construction sites during lockdowns despite the potential threat to workers’ health and welfare, and the risk of exacerbating community spread. The pandemic is a reminder that health and safety are key concerns across all industries, and mismanagement can have a significant effect.

The pandemic also illustrates the potentially disruptive nature of some emerging environmental and social risks due to the encompassing global dimension, unprecedented policy response, and rapid and severe tumultuous effects on economies. It’s affecting companies as well as stakeholders across the value chain, including employees, contractors, suppliers, consumers, and local communities, among others. While disruptions caused by emerging social and environmental risks are difficult to predict, we believe some, including those associated with climate change, represent similar systemic risks because they could disrupt economic systems across industries, value chains, and regions.

Though we’re still in the early days of the pandemic, we’re beginning to see that some management teams have successfully navigated the short-term challenges. In the longer term, we believe companies with stakeholder-focused governance may be better equipped to adapt for two reasons:

– The threat of pandemics isn’t new. The World Economic Forum has identified “infectious diseases” and pandemics as one of the main global risks in its annual Global Risk Report since it was first published in 2006. Companies that routinely assess long-term and emerging risks as part of their risk management may be better-positioned to anticipate them, prepare adequate contingency plans, and remain resilient to them in the long run.

– Sustainability risks, including social and health risks, affect a broad set of stakeholders across the value chain, from suppliers to employees, customers, and governments. Companies that regularly engage with relevant stakeholders may be better-positioned to adequately respond during a pandemic and defend their social license to operate than companies that haven’t fully assessed the ecosystems in which they operate.

In the coming weeks and months, we'll continue to identify the social risks that are driving credit ratings actions, but we'll also monitor how the indirect consequences of safety management and community engagement in this time of duress, for instance, can affect credit quality over a longer period than we currently anticipate for the pandemic and its immediate aftermath.

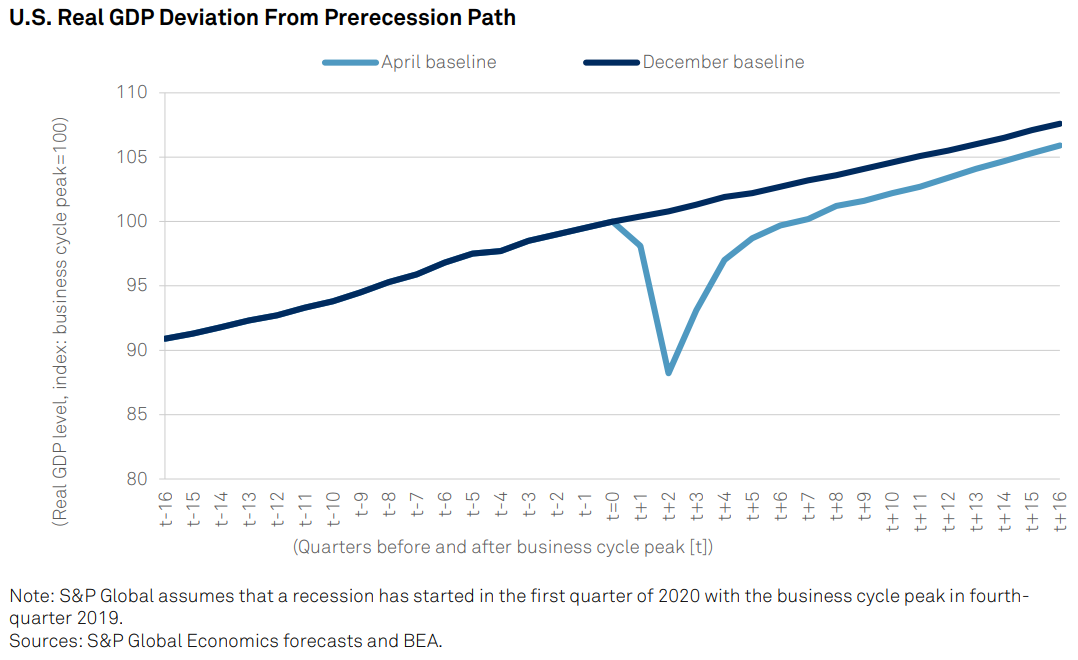

The path of the U.S. economy’s eventual emergence from recession has yet to become clear. We expect credit conditions to remain extraordinarily difficult at least into the second half of this year. Amid the severe economic stop associated with coronavirus-containment and -mitigation measures, companies’ cash flows and liquidity have, in many cases, disappeared and borrowing conditions remain oppressive to many others. On the other hand, the unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus coming from Washington may help stabilize the capital market and relieve some of the intense pressure on liquidity for borrowers across sectors. For the U.S., we now forecast a contraction in second-quarter (annualized) GDP of an unprecedented 34.5%, and that the economy will shrink 5.2% for the full year before rebounding with 6.2% growth next year and 2.5% in 2022. All told, we think the world’s biggest economy won’t get back to its end-2019 level until the third quarter of 2021.

Credit conditions in Asia-Pacific going into the second half 2020 will be very tough. Containment measures to stem the spread of COVID-19 pandemic have escalated regionally (outside China) with global confirmed cases doubling to more than 2 million over recent weeks. These measures, together with business and consumer behavioral changes, are having a wider and deeper effect on credit conditions in Asia-Pacific beyond what we estimated in late March. The COVID-19-affected U.S. and European economies are major trading partners of Asia-Pacific. While China has begun its economic recovery in the second quarter of 2020, the U.S. and Europe will likely be hit hardest in the second quarter of 2020. Consequently, for major economies as a whole, we anticipate economic recovery to be slow through the second half 2020 before gathering strength going into 2021. However, 2021 growth--driven by a rebound of demand--is not expected to make up for output lost during the current downturn.

Credit conditions continue slipping across EMs; we now expect a deeper global recession and a slower recovery. COVID-19 has rapidly spread across EM economies, and governments are taking restriction measures to contain the epidemic, halting most business activities and causing unemployment to soar. The combination of extended lockdowns in DM economies and domestic social distancing is deepening the shock to EM economies. Risks remain firmly on the downside given that longer lockdowns could impair household income, corporations' liquidity, and banks' asset quality. The risk of policy mistakes is on the rise, failure to contain the pandemic could lead to longer lockouts at some point and a deeper economic shock. Moreover, the absence of proper economic stimulus could derail recovery and prolong the economic downturn. Most EMs have limited wiggle room in light of weak per capita income, fiscal rigidities, high or rising leverage in some cases, and dependence on external financing in a few countries.

Extended lockdowns, a slower pace of normalization, and key trading partners embroiled in the same predicament have all contributed to a very sharp downward revision to European economic growth for 2020. We expect a deeper two-quarter recession in the eurozone with full-year growth falling by 7.3%. Top risks remain the pandemic not being contained despite all efforts, a scarcity of financing for indebted corporate borrowers, the re-emergence of global trade tensions including between the EU and U.K., and asymmetric fiscal costs from the pandemic placing renewed pressure on the EU’s cohesion.

Content Type

Location

Language