S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

S&P Global China Ratings — 23 Mar, 2020

Highlights

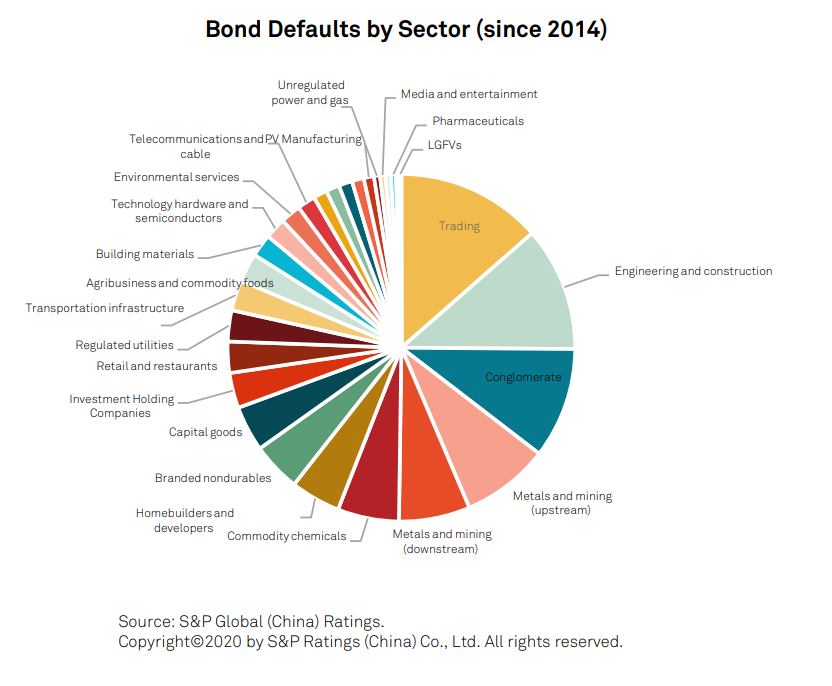

After analyzing the data behind defaults, we have found that in recent years trading, engineering and construction, conglomerates, metals and mining see more defaults than other sectors. At the opposite end, sectors with low default frequency include LGFVs, pharmaceuticals, unregulated power and gas, and media and entertainment.

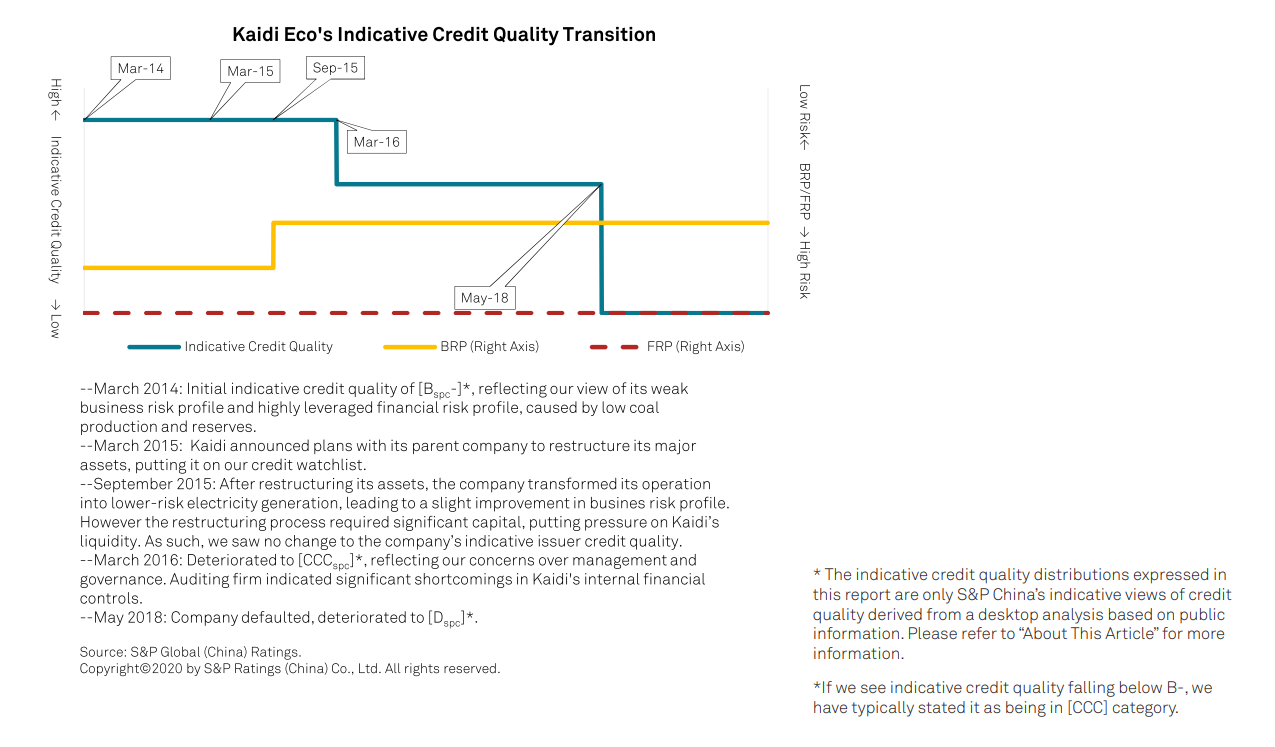

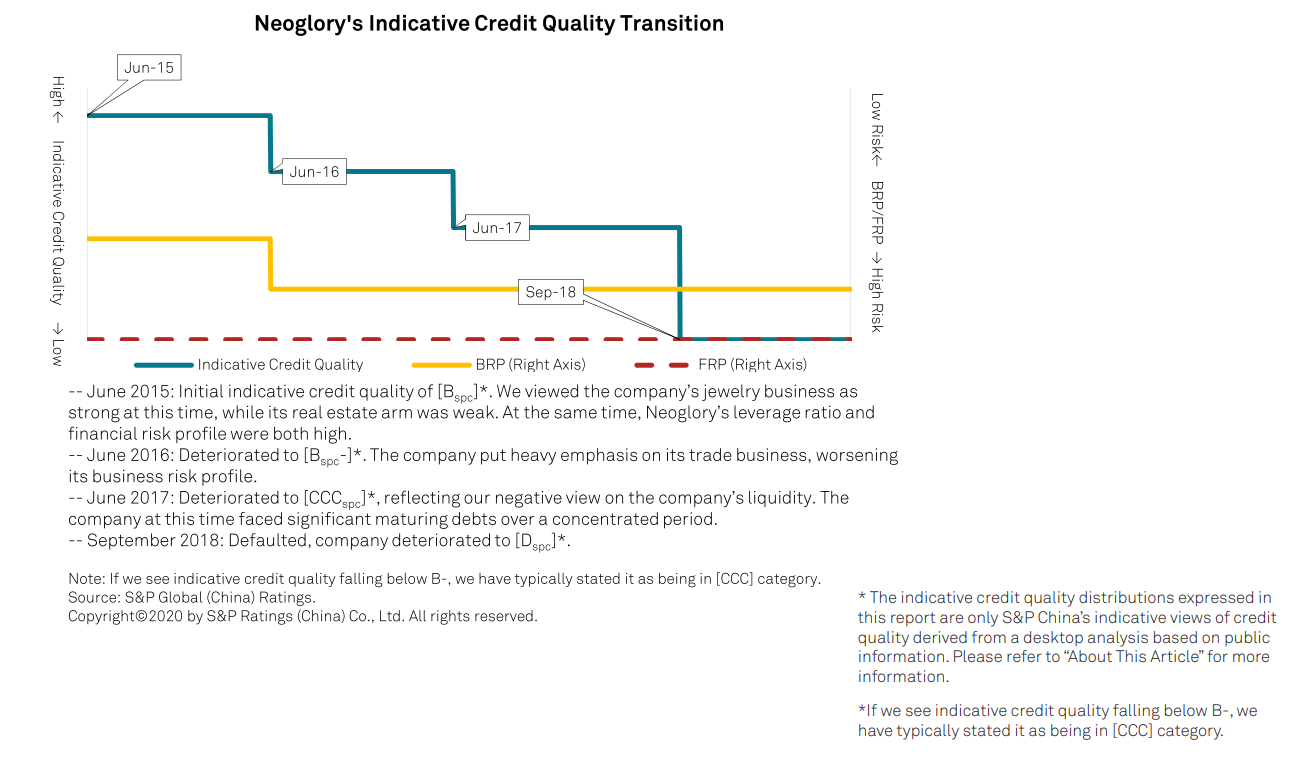

We have carried out a desktop analysis of five companies that defaulted, or faced significant debt repayment pressure, highlighting the red flags in the run up to default and charting the changes in business risk and financial risk profiles, as well as the major turning points that affected the company’s indicative credit quality.

We believe that close attention should be paid to how the risk differentials that exist between industries affect companies’ business risk profiles. We should be aware of different risk characteristics of certain industries and avoid overestimating some companies’ status as leaders in niche markets.

At the same time, to assess the risk of default, we believe that financial risk should be evaluated with a forward-looking perspective, while greater attention needs to be paid towards the potential impact of a parent company’s credit quality on that of its subsidiaries, particularly any negative influences.

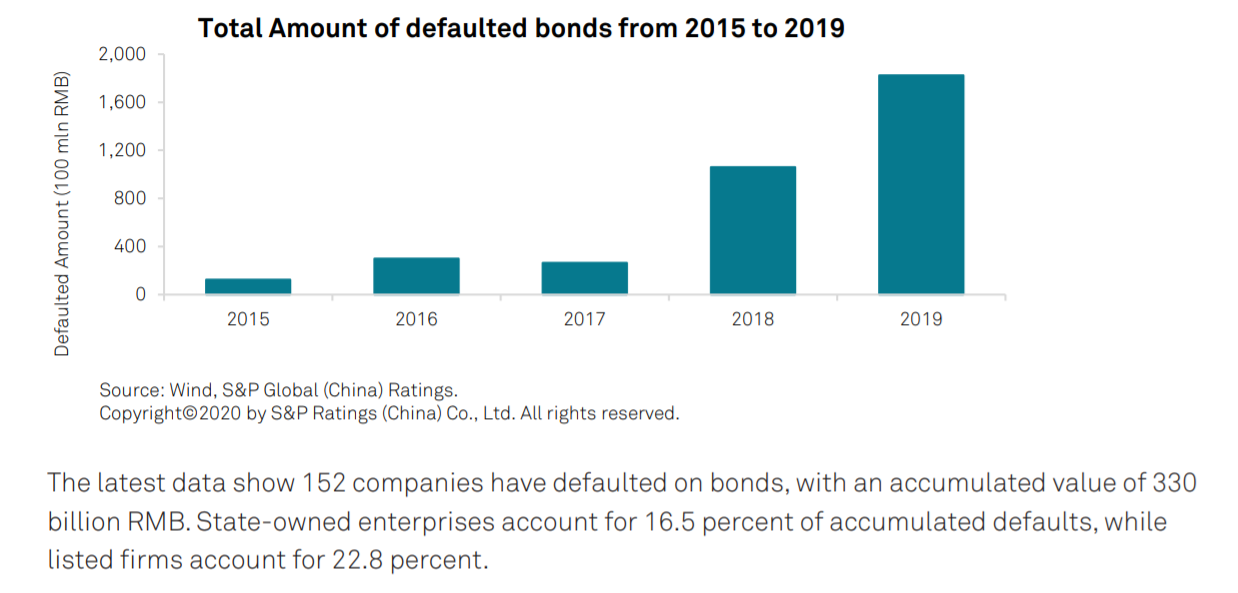

2014 was a turning point for China’s public bonds market, with the year marking the first recorded corporate default. Since then, defaults have steadily become more frequent. By the end of 2019, accumulated bond defaults reached around 330 billion RMB, involving 152 different companies. Against this backdrop, investors have grown increasingly vigilant towards the risk of default.

In this report, we provide a basic overview of corporate bond defaults over the past few years. Using S&P Global (China) Ratings’ methodologies, we have carried out a desktop analysis of five firms that defaulted or faced significant debt repayment pressure. These case studies highlight the events and changes in business risk and financial risk that can typically be seen in the buildup to a default, and show how such changes combine to affect the company’s indicative issuer credit quality.

We have also summarized some of the major red flags that appear before a corporate bond default, and provided insight into how S&P Global (China) Ratings assesses the risk of default. To clarify, this report only constitutes a desktop analysis. Please refer to “About This Article” for more information.

In the wake of rapid development and gradual structural improvements, China’s public bond market no longer follows the “rigid repayment” pattern seen in its infancy. Today, defaults occur at both a higher frequency and volume than ever before.

March 2014 saw the domestic market’s first default. For the following three years, the market saw annual defaults of around 30 billion RMB. However, from 2018 onwards, the frequency and volume of defaults gradually increased. According to data from Wind, 2018 saw 125 bond defaults worth approximately 100 billion RMB. That trend continued in 2019, with 178 defaults with an overall value of around 180 billion RMB.

The latest data show 152 companies have defaulted on bonds, with an accumulated value of 330 billion RMB. State-owned enterprises account for 16.5 percent of accumulated defaults, while listed firms account for 22.8 percent.

There are significant gaps between different sectors and industries when it comes to the volume of defaults. Trading, construction and engineering, conglomerates, mining and metals are among the worst-hit sectors, while local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), pharmaceuticals, unregulated power and gas, media and entertainment see relatively fewer defaults.

Our desktop analysis covers four defaulting firms — Fuguiniao Co., Ltd. (Fuguiniao); Kaidi Ecological and Environmental Co., Ltd. (Kaidi Eco); Reward Science and Technology Industry Group Co., Ltd. (Reward Science and Tech) and Neoglory Holding Group Co., Ltd. (Neoglory), as well as Kangmei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Kangmei Pharmaceutical), which came under huge debt repayment pressure and received wide market attention. Our analysis of each firm starts two to three years before the date of default (or major credit event in the case of Kangmei), and highlights changes in the companies’ business and financial risk profiles, as well as various events that combined to impact on indicative issuer credit quality

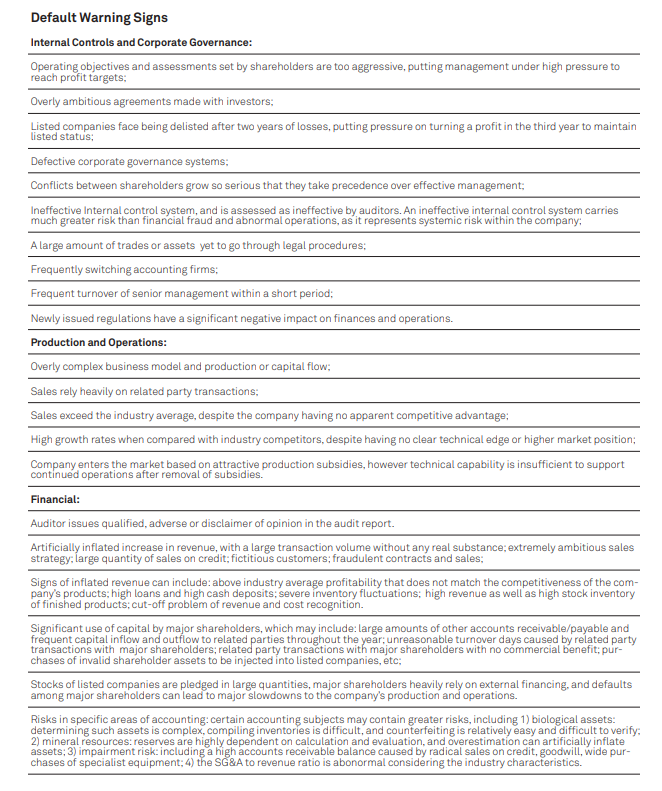

In most cases, irregularities and warning signs typically appear before most debt defaults. These red flags include but are not limited to:

Table 1

The following three areas are useful to our analysis in gauging default risks.

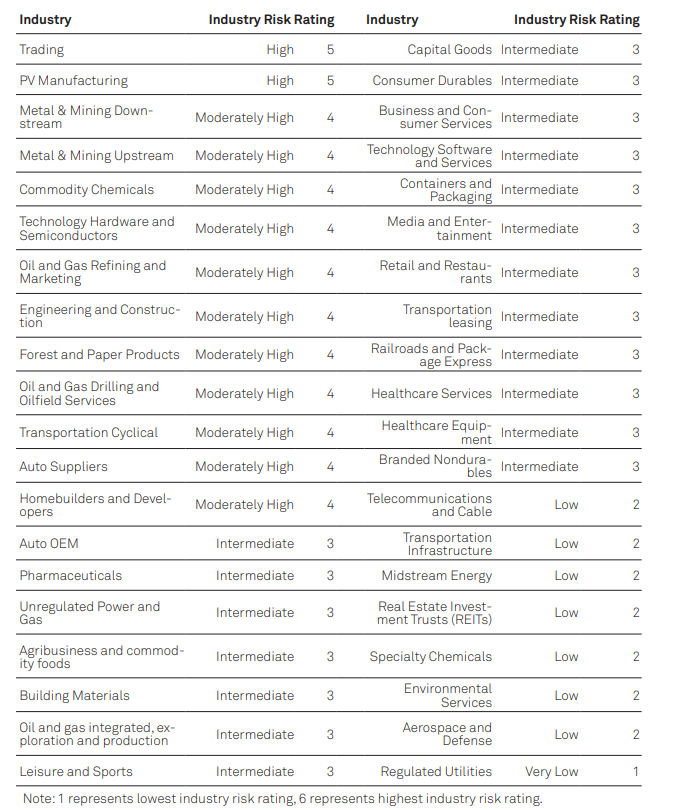

We don’t view industry risk as being the same among all industries. In fact, various risk characteristics could lead to different levels of health and stability in markets in which a company operates. With this in mind, we use “industry risk” as a starting point and key basis for analyzing a company’s business risk profile, before combining that with the company’s competitive position to obtain an overview of the business.

TABLE 2

We focus on how differentials in risk between different industries influence a company’s business risk profile. In our view, being a leader in one industry is no guarantee that that company has similar attributes to leaders in other sectors. Two different companies with similar competitive position rankings in their own respective sectors may have a different business risk profile assessment due to the different industries that they operate in.

For example, for two different companies with strong competitive positions in their own respective industries, we may expect companies engaged in regulated utilities (industry risk level 1) to have a stronger business risk profile than those in the photovoltaic manufacturing sector (industry risk level 5). In other words, we believe enterprises in high-risk industries need to have a better competitive position in order to compete with enterprises in low-risk industries when it comes to their business risk profile assessment.

A look at the distribution of bond defaults across various sectors confirms our assessment of industry risk. The higher the industry risk score, the higher the amount of defaults in that industry. Defaults among companies with an industry risk of 5 are relatively low, mainly because there are only two industries with such a high-risk level: trading and photovoltaic manufacturing.

For companies that are top firms in niche industries, we believe it is important to avoid overestimating their business risk profile and ability to combat risk. When it comes to assessing the business risk profile of such a company, we choose to compare it against the overall makeup of its wider industry, rather than against other individual firms belonging to that niche sub-sector.

For example, when looking at the competitive position of a company mainly engaged in wind power, we will not only compare it with other players in the wind power sector, but also with companies engaged in hydropower, solar energy, waste power generation, water and gas supply and other related businesses. We classify these sub-sectors as being part of a wider "regulated utilities" industry.

There are two reasons for this. Firstly, China has a sound industrial structure with many subsectors. It is usually possible to identify many "leading" companies within niche markets. But if the products of these firms are too specialized and demand is too narrow, any changes in downstream industries can have significant impact on these companies. When these companies are looked at alongside firms that are leaders covering a wider range of markets, we view the latter to be more resilient.

Secondly, excessively niche businesses may face greater refinancing pressure, because the field of competition for financial resources typically covers a broader domain, rather than solely within that narrow sub-sector. When financial institutions allocate assets, they may set caps on investing in large industries. In such circumstances, there is intense competition between firms in niche industries to access financial resources.

S&P Global (China) Ratings typically combines financial results of the past two years with estimates for the following three years to evaluate companies’ overall financial risk profiles. We typically add greater weighting to the forecast in our analysis. We typically rate “through the cycle”. For example, when we estimate the price of an upstream industry company’s main product and use it as a basis for evaluating its future financial performance, we should not overestimate the profitability of the company when the price peaks. We should also avoid exaggerating financial risk when that product’s price is at a low point.

When evaluating the issuer credit quality of a company, we also look beyond its own situation and, if applicable, focus on the potential impact of its parent company's credit status. If the parent company's credit quality is strong, it may improve the subsidiary company's credit quality. But in cases where a parent company’s credit quality is weaker than its subsidiary, then the parent may be more of a burden, acting as a cap on the subsidiary’s credit quality.

This drag occurs because the parent company may use the resources of its subsidiary to ease its own debt repayment pressure. There are many ways for parent companies to co-opt the resources of their subsidiaries, such as intercompany loans, divesting subsidiaries’ assets into other companies, or forcing the subsidiary to acquire assets belonging to the parent company at unreasonable prices. At the same time, significant financial problems facing the wider group may seriously affect the normal production and operations of its subsidiaries, negatively affecting their credit quality.

The "strong subsidiary, weak parent" situation is widespread, especially among listed companies. China has strict requirements for the listing of companies, so most groups will package their best assets together in order to list. Within the parent group, listed companies usually have the strongest profitability, the best asset quality and the lowest debt burden.

For the listed companies mentioned above, if the parent has a heavy debt burden or its business situation is much worse than that of its subsidiaries, we may expect the parent’s credit situation to have a negative impact on the listed companies. However, if the listed company is completely isolated from the influence of the parent, and the parent company is unable to exert significant influence on the operations or finances of the listed company, then we may expect the credit quality of the parent company to have no influence on the subsidiary in question.

Content Type

Location

Segment

Language