Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

S&P Dow Jones Indices — 10 Nov, 2020

For the first time, the SPIVA Europe Mid-Year 2020 Scorecard introduced risk-adjusted performance evaluations of European equity funds. Previously, proponents of active fund management may have criticized the SPIVA scorecard for measuring performance on a return-only basis. They may have argued that this only told one side of the story, and that their abilities should also have been judged on the level of risk that they employed. After all, given funds with similar returns, would investors not prefer the fund with lower risk? A similar question could arise when comparing active funds with their benchmarks. Do benchmarks perform better simply because they take on more risk? Adjusting returns by the risk involved allows us to tell the whole story and more closely compare how well active funds and their benchmarks performed per unit of risk taken.

Do European Benchmarks Still Perform Well on a Risk-Adjusted Basis?

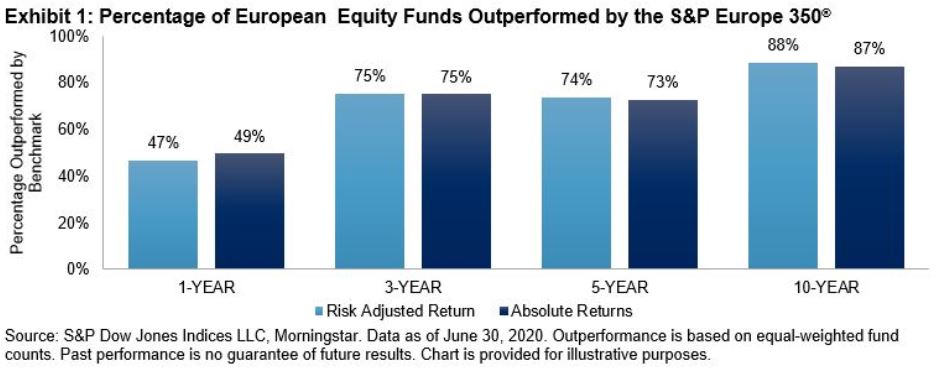

In our latest SPIVA Europe Scorecard, a fund or benchmark’s risk-adjusted return was computed as the annualized average monthly return divided by annualized standard deviation of the monthly return for the period observed. The intuition is straightforward: rather than looking at absolute returns, we looked at the returns attained per unit of risk borne by the investor. Exhibit 1 shows the percentage of European equity funds outperformed by their benchmark and compares the metrics computed using different measures of performance. The percentage of funds that outperformed the benchmark was largely unaffected by adjusting the performance by its risk, and the notion that active funds may yield lower returns because they were less risky did not seem to be confirmed by the data. Otherwise, once adjusted for risk, we should have seen a much lower percentage of active funds being outperformed by their benchmark across the different time periods. Instead, we saw similar numbers, which increased steadily when looking at the medium to long term. This highlights a stylized fact already well substantiated by our SPIVA scorecards: in the long run, the majority of active funds failed to beat the benchmark.

The U.K. Case

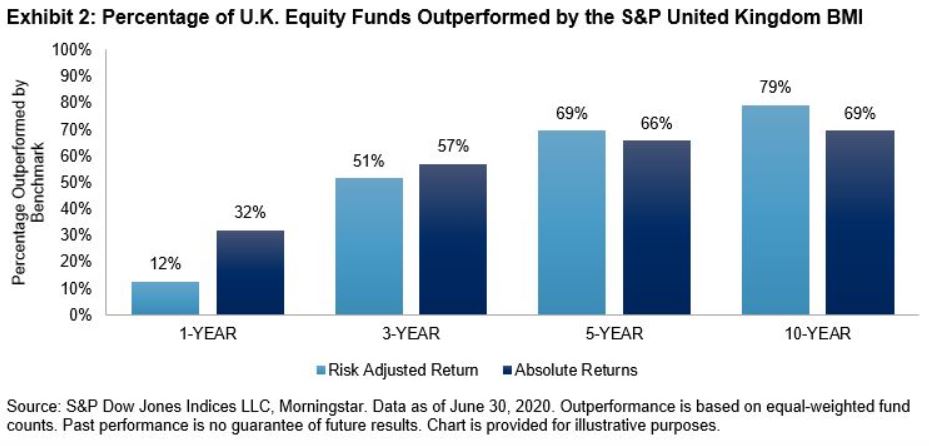

Exhibit 2 shows the results of carrying out the same exercise for U.K.-focused equity funds. In the short term, active funds performed better on a risk-adjusted basis: only 12% were outperformed by the benchmark on a risk-adjusted basis, compared with 32% when looking at absolute returns. However, when looking at longer periods, the same pattern as was seen in Europe emerged. Not only did it seem harder for active funds to beat their benchmark in absolute performance terms, but their risk-adjusted performance could not keep up either. Across the 10-year period, the relationship seen in the short term was inverted; on a risk-adjusted basis, a larger percentage of active funds were outperformed by the benchmark compared to an absolute return basis.

Our SPIVA Europe Mid-Year 2020 Scorecard also shows risk-adjusted performance metrics for other European fund categories. In most cases, the conclusion was similar: risk adjustment did not seem to save active funds from being outperformed by their benchmarks. With this new addition to the SPIVA Europe Scorecard, it begs the question, “Are there any more excuses left for active managers?”

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.