Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

S&P Dow Jones Indices — 18 Mar, 2020

This article is reprinted from the Indexology blog of S&P Dow Jones Indices.

The fall in equity market values since February’s peak has been sudden and dramatic. During this period, the equity markets have functioned well at their primary task of facilitating price discovery at a time when values were changing rapidly. Equity investors who wanted to trade have been able to trade. (Whether they were wise to do so is a separate question.)

This is in no small part due to the liquidity provided by index-linked vehicles. Index funds have been part of the investment landscape for nearly 50 years, during which time superior performance and low cost have earned them a growing share of investor assets. What’s less well-appreciated has been the growth of a trading ecosystem linked to indices, most importantly to the S&P 500. The vast majority of trading in index-linked vehicles is not done by index funds, but rather by active investors and traders.

The coronavirus-induced bear market which we’re now enduring illustrates the logic of index-linked trading well. A pandemic of still-unknown duration and severity can be expected to affect every business adversely. The degree of adversity will obviously vary across industries, with some (e.g., airlines and hotels) suffering more than others. But investors who want to adjust equity exposures quickly will be far better served by trading an entire index than by trying to sort out relative winners and losers in the traditional way.

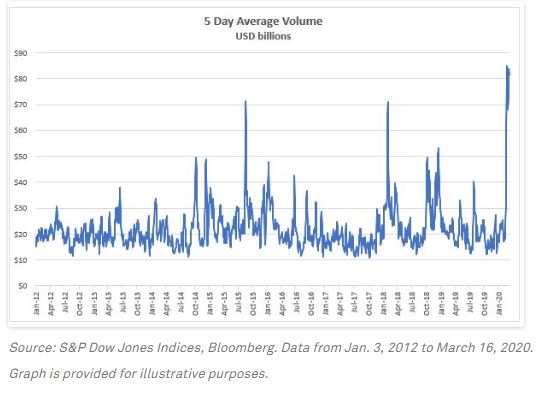

In this environment, it’s unsurprising to see higher volumes and higher dealer spreads, as we did during the last two weeks’ market carnage. It’s estimated that in the first week of March, “exchange-traded products powered more than a third of equities trading on U.S. exchanges.” We can see this effect in Exhibit 1, which measures the average value traded in the largest ETF tracking the S&P 500. Normally the most heavily-traded issue in the U.S. market, daily volume skyrocketed at the end of February.

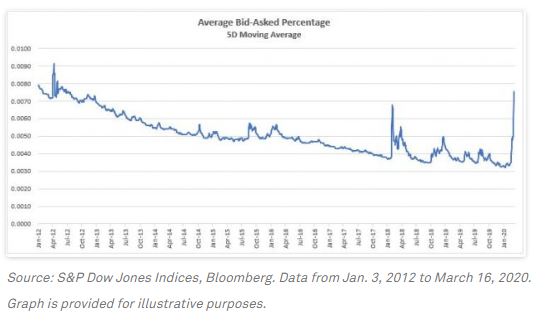

At the same time trading costs rose, as measured by the width of the bid-offer spread pictured in Exhibit 2.

As recently as January 2020, spreads were as low as 0.003%; more recently they doubled. Spreads are not at all-time highs, however, and trading the ETF is still much cheaper than trading individual securities.

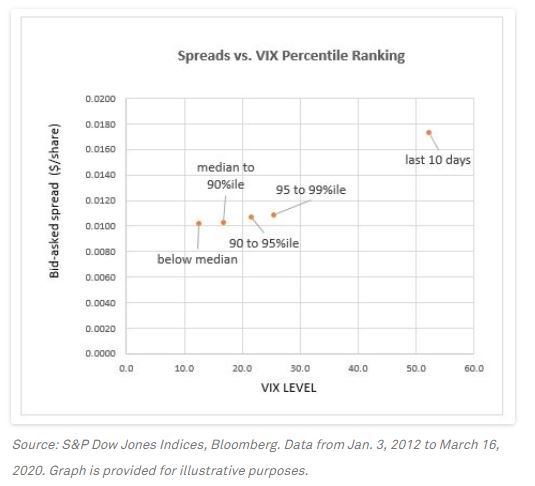

It’s important to understand that the widening of dealer spreads is a natural and appropriate reaction to the extraordinary levels of market volatility we’ve witnessed since mid-February. Exhibit 3 describes the relationship between the VIX index and the ETF’s bid-asked spread. When VIX is at or below its median level, for example, spreads average just over $0.01/share. The relationship slopes gently upward over most values of VIX. Extreme levels of VIX, however, indicate heightened dealer risk, and thus increased bid-asked spreads.

At time when it was badly needed, index-based products helped to ensure equity liquidity was available at a reasonable price.