Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

By Alexandre Birry, Cihan Duran, CFA, Jon Palmer, Erkan Erturk, Harry Hu, Charles Mounts, Jennie Brookman, and Maddy Corcoran

Highlights

Evolving regulations will define the future shape of the crypto ecosystem over the next two years.

The “crypto winter” and related collapse of some projects and crypto assets have prompted significant losses, exposed idiosyncratic risks and vulnerabilities within protocols, and highlighted systemic concerns within the crypto landscape. As a result, it has sharpened policymakers' awareness of the need to regulate the crypto and decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystem.

Reduced asset prices and activity may offer only a temporary reprieve from the urgency of the regulatory task. Key priorities for policymakers will likely include consumer protection, financial stability, market conduct, and anti-money laundering rules, while also striking a balance that enables and fosters continued innovation in the financial markets.

The policy stance will vary, and legislation may move at different speeds and in different directions between regions. The significant losses caused by the recent rout appears to have toughened the regulatory resolve of even some of the more crypto-friendly authorities. But as the market thaws, there will likely continue to be key differences between policymakers. And policymakers will have to contend with a difficult macro and geopolitical context, as well as some unique features attendant to this emerging ecosystem.

Download PDF

Regulation is shaping up to be a defining feature of the crypto ecosystem over the next two years. The current market downturn and related collapse of some projects and crypto assets have prompted significant losses, exposed idiosyncratic risks and vulnerabilities within protocols, highlighted systemic concerns within the crypto landscape, and sharpened policymakers' awareness of the need to regulate the crypto and decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystem. Reduced asset prices and activity may offer only a temporary reprieve from the urgency of the regulatory task. We believe that for policymakers, key priorities will include consumer protection, financial stability, market conduct, and anti-money-laundering rules, among others, while also striking a balance that enables and fosters continued innovation in the financial markets (see "Key Areas Of Regulatory Focus" graphic, below).

The policy stance will vary. Mindful of the purported benefits of this emerging ecosystem, certain jurisdictions will seek simply to better frame it. Wary of systemic risks, others may strive to tame it. And in the race to become a global hub--or for other geopolitical motives--a few may try to game it. In this report, we explore the regulatory progress and outlook for specific types of digital assets and activities, and for a few key jurisdictions. It is part of a series of publications we have released on the digitalization of markets, which includes "Digitalization Of Markets: Framing The Emerging Ecosystem," published Sept. 16, 2021, and "Stablecoins: Common Promises, Diverging Outcomes," published June 15, 2022.

Key Areas Of Regulatory Focus

Source: S&P Global Ratings.

Copyright @ 2022 by Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC. All rights reserved.

An acceleration in regulatory initiatives doesn't necessarily protect traditional finance incumbents. Building a coherent regulatory framework around digital assets and DeFi may legitimize and accelerate industry development, by attracting new customers and incentivizing entrants that pose a risk to traditional finance incumbents' operating models. We believe that regulations may, on balance, allow for more permeability between the traditional finance (TradFi) and DeFi worlds.

The Challenges Of Regulating Crypto

Source: S&P Global Ratings.

Copyright @ 2022 by Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC. All rights reserved.

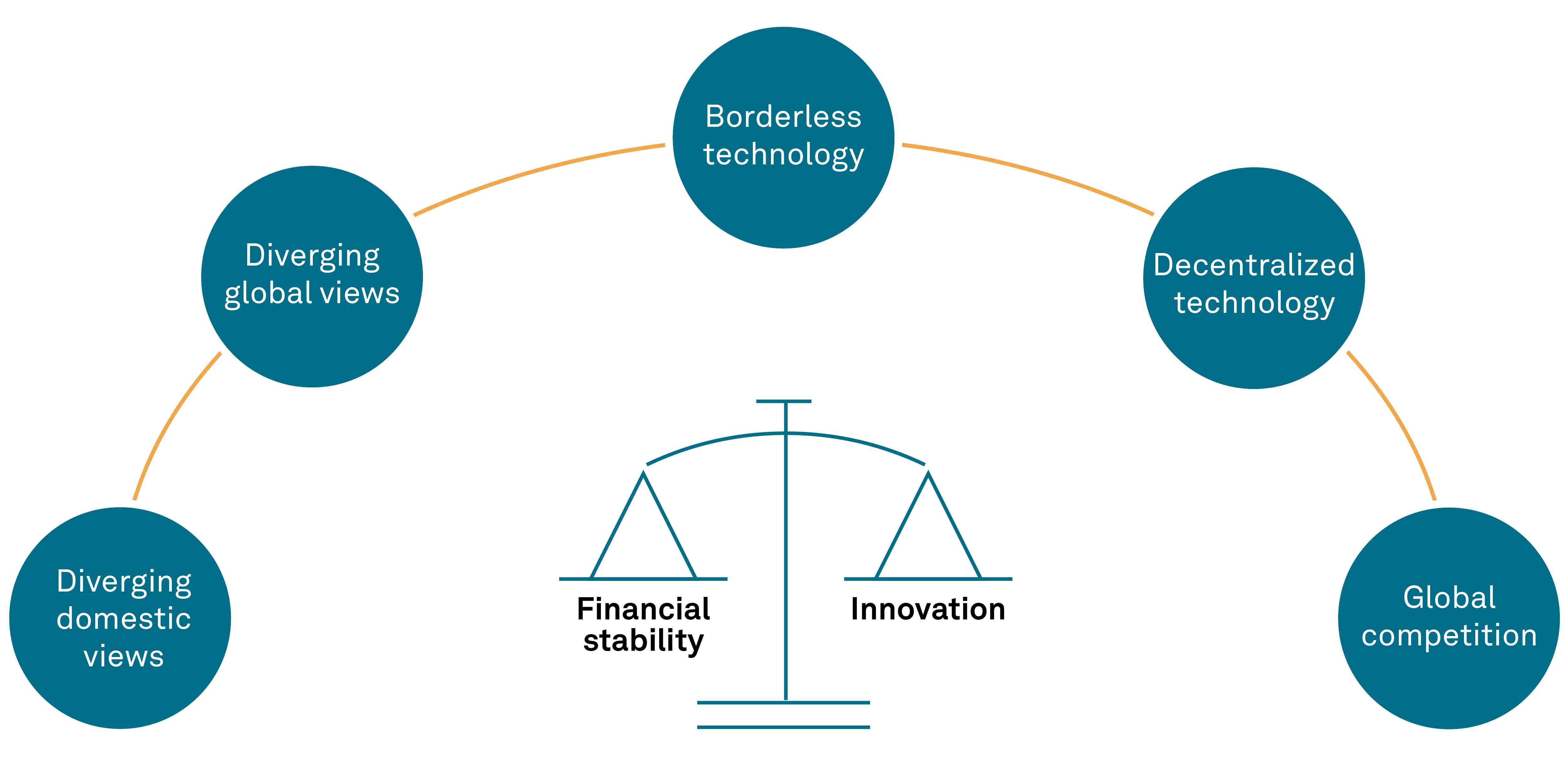

Policymakers will have to contend with a difficult macro and geopolitical context, as well as some unique features attendant to this emerging ecosystem. On the back of the global financial crisis of 2007-2009, regulators have demonstrated their willingness and ability to implement coordinated, comprehensive, and effective measures to reduce risks in the global financial system. The statement released by the Financial Stability Board on July 11, 2022, highlights that this ecosystem "must be subject to effective regulation and oversight commensurate to the risks they pose, both at the domestic and international level". Yet, in terms of regulating this new world of crypto and DeFi, the market adage that past performance is not indicative of future results could hold true. Standard setters and supervisors across regions will have to contend with several complicating factors, such as:

Diverging domestic views: Cryptocurrencies and DeFi are polarizing topics in domestic political contexts that are often already polarized, while some of these digital assets are difficult to classify (e.g., are they commodities, or currencies, or securities, or something else?) with cascading implications for who should supervise them. Stances on these topics also may vary greatly between politicians, central bankers, and regulatory bodies;

Diverging global views: The policy stance will likely remain fragmented across jurisdictions. Conflicting (geo)political objectives can underpin these differences, with the future of money and the status quo of the global financial order at stake. Attitudes to privacy also vary across countries, as does the level of trust in institutions, and the broader population's access to finance;

Borderless technology: One key attraction of the technology is that internet access is the only requisite to use many protocols. The blockchain technology at the core allows developers to operate from almost any location, and the protocols can be made available across borders in an instant;

Decentralized technology: A key question arising from blockchain technology is whom to regulate when authority is decentralized. In many cases, we believe that decentralization will only be partial, with centralized gateways to protocols or permissioned blockchains allowing for greater supervisions. Another question arises around who is accountable when code alone determines the execution of contracts; and

Global competition: Domestic policies and regulations are key elements of a jurisdiction's appeal. In this fast-moving context, the calibration of these policies and regulations can be an opportunity for jurisdictions to establish themselves as hubs of a burgeoning global industry.

We see strong differences in the policy and regulatory approaches between--and often within--jurisdictions; for instance, in terms of policymakers' support for a regulatory, legislative, and operating framework that is conducive to the local development of DeFi and crypto-related activities. The significant losses caused by the recent rout appears to have toughened the regulatory resolve of even some of the more crypto-friendly authorities. But as the market thaws, we believe that there will continue to be key differences between policymakers.

Equally, we believe that jurisdictions are at very different stages of policy formation, with varying levels of progress in the development of a comprehensive and predictable regulatory and legislative framework for these activities. In the above infographic (see "Relative Assessment Of Crypto Regulations For Selected Jurisdictions"), we map our view of these differences in two dimensions for selected jurisdictions. At the same time, we recognize the qualitative nature of these appreciations, as well as the situation's fluidity. The policy stance of certain jurisdictions appears clear: for example, China has banned all crypto activities and is unlikely to reverse this decision, whereas El Salvador passed a law in 2021 that made bitcoin legal tender. But most jurisdictions are somewhere in the middle. In those cases, balancing motives such as innovation, greater competition, and access to new services against considerations including financial stability and customer protection have led to more nuanced, or yet-to-be-defined policy stances. Policymakers face the difficult task of finding a risk-based regulatory approach while keeping a technology-neutral stance to avoid unnecessarily curbing innovation. Even within some of these jurisdictions--whether we're looking at different U.S. states or countries within the EU--the picture is increasingly heterogenous.

All in all, regulation and legislation will likely move at different speeds and, in some cases, in different directions between regions. But we hold one thing for sure: despite the challenges it faces, regulation will be key in defining how this ecosystem evolves, how far it goes, and how DeFi interacts with--and possibly transforms--TradFi.

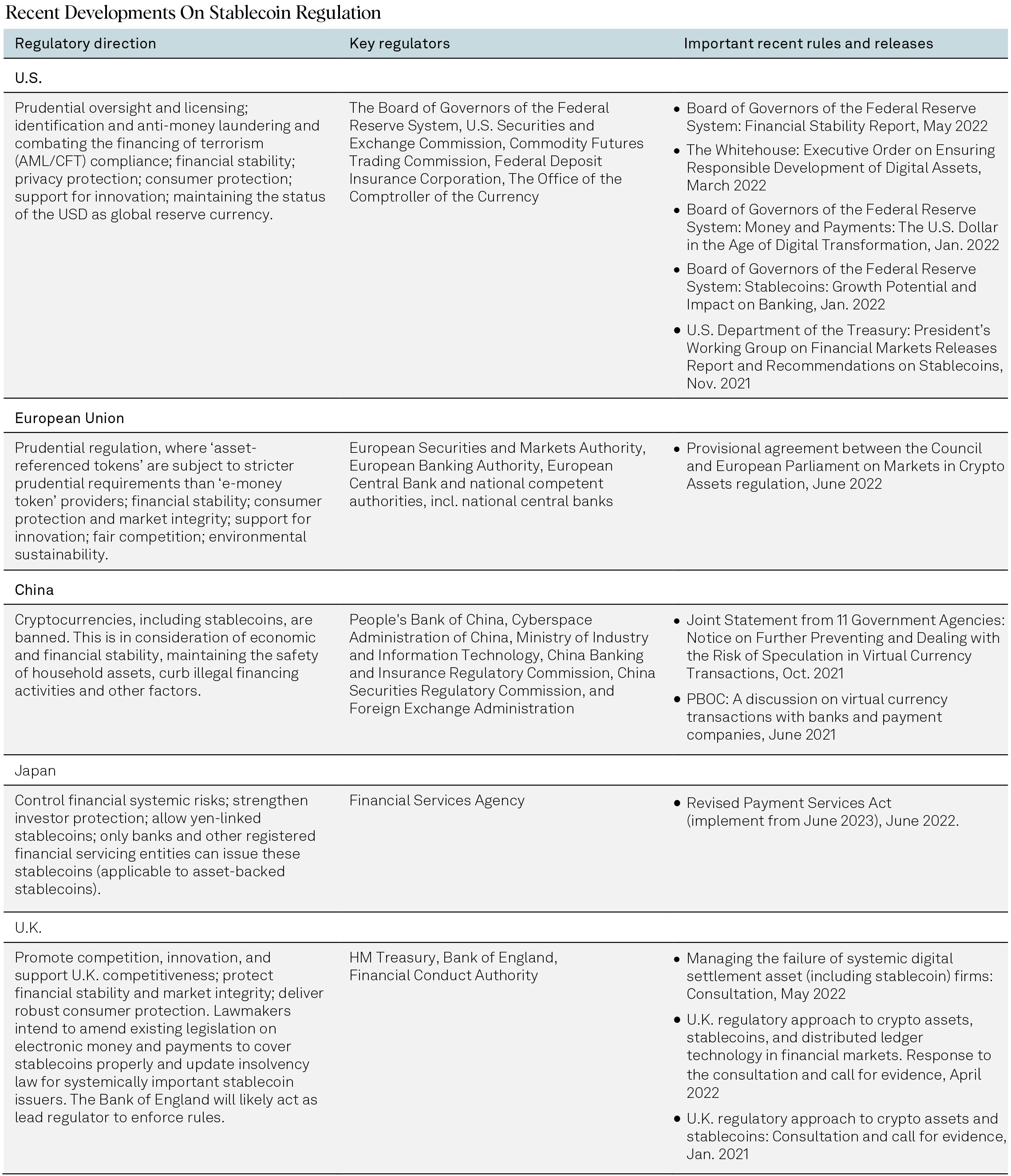

Financial stability is front of mind for financial regulators. The key issue is how stablecoins can coexist alongside the traditional financial system without materially elevating systemic risks.

This report was originally included in "Stablecoins: Common Promises, Diverging Outcome," published June 15, 2022.

The fast growth and use of stablecoins as payment is accelerating regulation. Stablecoins are typically more efficient for global payments and transfers than traditional finance, where the average international remittance fee is about 6% of the transfer value and could take several days to process. As adoption increases, there is an increasing propensity to use stablecoins as payment, a key foundation of traditional financial systems.

To proactively manage financial stability concerns, we are seeing global regulators investigating and taking a stance on stablecoins. For instance, the Financial Stability Board highlighted in its July 2022 statement the need to "address the potential financial stability risks posed by crypto assets, including so-called stablecoins". We believe the regulatory work on this will intensify over the next one to two years and could reshape how stablecoins are governed, managed, and used.

Use of stablecoins for payments needs regulatory certainty. While the private sector is exploring stablecoin retail payment applications, progress has been slow absent clear regulations and licensing, which are still largely in development around the globe. This includes the U.S., where an executive order signed in March highlights the policy direction for which digital assets will be regulated. As over 95% of stablecoin values are linked to the U.S. dollar, stablecoin regulation--and the potential development of the U.S. central bank digital currency (CBDC; for simplicity, e-USD)--could reshape the utilities, competitive dynamics, and perceptions of stablecoins. Early implementations of stablecoin debit cards, such as Coinbase’s USDC debit card, have been rolled out in the U.S. and Europe. Announcements from the payment processor Stripe to support USDC payments will likely further accelerate stablecoin adoption into payment services. By replacing the chain of intermediaries and service providers linking payers and payees, smart contracts automate backend processes and simplify transactions on a commonly distributed digital ledger.

Stablecoin’s advantages over domestic digital retail payments are narrower, because both instantaneously settle. However, stablecoins have the potential to decrease fees to merchants because they have fewer intermediaries, especially as transactions become increasingly peer-to-peer in nature. Stablecoins have potential as an alternative means of payment for households and businesses, and their adoption could be rapid due to network effects and increasing crypto awareness. While there are risks, stablecoins also aspire to help the underbanked to better access financial services, with a positive impact on financial inclusion, particularly in emerging markets.

Globally, the regulatory response has varied from an outright ban to full crypto adoption. In the U.S., a licensed approach is being discussed. There is broad consensus on the efficiency gains of blockchain-based transactions, though expectation gaps remain between authorities and parts of the crypto community (including stablecoin holders) around the degree of decentralization lost to handle concerns such as know your customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML). Cryptocurrencies are a global phenomenon, and related activities could move from one jurisdiction to Ir to benefit from regulatory arbitrage.

While there are investor protection concerns, the crypto ecosystem can also be a source of wealth and fiscal income. The status as the dominant international reserve currency could be another consideration in the legislative process for e-USD adoption. We believe non-reserve currency-backed stablecoins could come under heavier regulatory scrutiny because issues around non-credit-based shadow money supply and seigniorage could surface. These matters would be more pronounced for undercollateralized stablecoins.

It is unclear if regulations could reach stablecoin issuers wishing to remain unregulated by moving their operations outside of applicable jurisdictions. We expect that assigning regulatory approval and deposit insurance for regulated stablecoins will relegate unregulated stablecoins to lesser, more speculative roles and slow their growth without institutional adoption.

Systemic risk is the primary regulatory focus. How stablecoins coexist with the traditional financial system without materially elevating systemic risks is one of financial regulators’ main concerns. Issues such as adequate and transparent reserve backing, asset fire sales under stress, and the consequential shock to financial institutions and markets are actively discussed. Market concentration with existing stablecoin providers could also heighten the impact in a risk event. While the effect on payment systems is also mentioned, the risk is thus far limited, as stablecoins are not yet used as a widespread means of payment.

At the financial institutions level, operational and cyber risk management and controls are likely focus points for prudential supervisors. In addition, stablecoin and crypto-related customer protection and AML efforts are likely to be integrated with existing regulatory frameworks once the necessary infrastructure and policies for identity verification are embedded.

Crypto assets fall under existing laws and regulations when they meet the relevant definitions of a security. But both the appearance and nature of crypto assets can cloud their classification, so that they can fall outside of European regulation and may not comply with regulations in the U.S.

Digital securities include digitized traditional securities and some crypto assets. Many of the crypto assets that have been sold to the public through initial coin offerings in the U.S. are likely securities, according to SEC Chairman Gary Gensler (see "Remarks Before the Aspen Security Forum"). Europe, however, has a less prescriptive classification of financial instruments under the existing Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID). We understand that the EU’s Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) legislative proposal aims to regulate crypto-assets not covered as financial instruments by MiFID (including stablecoins and utility tokens, among others).

Decentralized finance (DeFi) projects that issue crypto assets may fall outside of securities laws and regulations. This could have negative implications for investor protection and market integrity, as stakeholders responsible for developing and marketing a project can be extricated from it as retail investors buy in. This could leave retail investors assuming a disproportionate amount of risk if the project fails (see "IOSCO Decentralized Finance Report," March 2022).

Many crypto assets do not resemble traditional securities. In the U.S., the SEC uses the Howey test, derived from the 1946 Supreme Court decision in SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., to apply the 1933 Securities Act. All four conditions of the Howey test must be met for an asset to be a security: (1) an investment of money; (2) in a common enterprise; (3) with a reasonable expectation of profit; and (4) through the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others.

Crypto assets offered in the U.S. could be deemed securities when the project team behind the offering constitutes a common enterprise, the marketing material for the offering promotes an economic incentive, and if holders of the crypto assets must rely on the efforts of others to realize those economic incentives. To offset this risk, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), foundations, and other governance structures have been set up to operate many new projects. Often, these are registered outside the U.S. in more favorable crypto jurisdictions.

Many crypto projects are funded by venture capital funds, but when capital is raised through a crypto asset offering to finance a blockchain project’s development, it is increasingly difficult for the crypto assets offered to not meet the definition of a security under the Howey test. In Europe, classification as a financial instrument is less prescriptive, but an expectation of profit appears to be a consideration for future regulation of crypto assets (see "Advice on Initial Coin Offerings and Crypto-Assets" and "Annex 1").

The classification of a crypto asset as a security could change over time. A crypto asset may be considered a security when it is first issued. However, if after the initial sale the crypto asset is minted only through a clearly defined protocol (staking or farming rewards) and the project is run by a fully decentralized organization with no common enterprise responsible for it, then it would no longer meet the second condition of the Howey test in the U.S. Even if a crypto asset meets the definition of a security when it is first issued, it may not continue to meet the definition.

Crypto asset investors face substantial risk without built-for-purpose laws and regulations. Most crypto assets are issued without adequate information to make an informed investment decision. Marketing material for these offerings can be misleading. Oversight is currently relatively limited. SEC enforcement actions represent a small fraction of the number of active crypto assets and will be difficult to expand without clearer, built-for-purpose regulation that more completely defines the crypto asset regulatory framework.

Standardized differentiation between types of crypto tokens in Europe aims to impose a proportionate regulatory burden for blockchain-related startups. It also supports investment by standardizing investor protections that improve blockchain project transparency.

A subset of crypto assets, crypto tokens (protocol tokens that sit atop public blockchains) are largely issued outside of existing laws and regulations through various types of initial token offerings. How the token is initially offered and, subsequently, how it is used, may or may not cause it to fall under existing definitions of a security at the time of issuance. However, existing laws and regulations may not always allow authorities to address these nuances. In the U.S., regulators have taken an enforcement-through-litigation approach. In Europe, authorities have issued guidance and warnings to consumers as comprehensive legislation is finalized. In the current environment, investing in crypto tokens offers little investor protection.

A standardized differentiation between types of crypto tokens is not always straightforward. Crypto tokens are typically integrated into protocols that are programmed using smart contracts on public blockchains. The most common use of tokens is to create incentives that facilitate activity in an application and the surrounding network. Incentives are integral for blockchain projects to create scale, making crypto tokens an essential component of a project’s entrepreneurial strategy. Initial token offerings are also an efficient way for blockchain-related startups to create network effects and bring users onto their platform. This leaves policymakers and regulators with the difficult task of balancing investor protection and innovation.

The lines differentiating crypto tokens can be blurred, and the classification of a crypto token can change over time. For example, crypto tokens are increasingly used for digital privacy, governance, and proof of participation, and are deliberately coded to reduce and sometimes prevent extrinsic value. These innovations are important, yet they contribute to regulatory ambiguity. The lines are further blurred when tokens are used as the native currency of a public blockchain, although those tokens are often referred to as coins because they are typically less programmable and used to operate the blockchain network.

It can be difficult to determine when a crypto token is not a financial instrument. The differentiation between crypto tokens is an interesting development in the EU's Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) proposal because it might allow for a relatively light regulatory burden for startup blockchain projects that issue tokens that do not qualify as securities, supporting innovation by avoiding the creation of excessive barriers to entry. However, one of the elements that typically defines securities is an expectation of profit, and it can be difficult to eliminate expectations of profit when an initial token offering is conducted in a manner that attracts participants with profit motivations, as is often the case. Even built-for-purpose laws and regulations may need clear and consistent guidance that outlines when a crypto token will not qualify as a security.

Crypto Tokens Are At The Core OF DLT Innovation

Source: S&P Global Ratings.

Lack of legal and regulatory clarity is constraining growth and innovation and increases risk for investors. The current environment produces an adverse selection problem where limited transparency can lead to fraud and ill-conceived projects that can cloud the market. Built-for-purpose laws and regulations could pull in established firms waiting for guidance and would provide clarity for new entrants. We believe regulatory clarity and better investor protection will increase investment and support innovation.

Cihan Duran, CFA | Alexandre Birry

Decentralized finance (DeFi)-based projects are still largely unregulated, because of their borderless and autonomous nature. But to achieve greater regulatory certainty and scale, platforms may need to settle for permissioned access points that fall within supervisory scope.

Lending (and borrowing) is a key pillar of DeFi. It is the second-largest DeFi sector and constitutes almost 15% of total value locked (TVL; U.S. dollar-equivalent) relative to all DeFi sectors as of June 2022. In summary, lenders receive interest in the form of their deposited token or a basket of other tokens, including the native token of the underlying protocol where assets are deposited. At the same time, borrowers can use these funds if they overcollateralize the amount they borrow in the form of other cryptocurrencies. With enough collateral, any borrower can have access to liquidity for trading and more. Borrowing costs are determined continuously with an autonomous algorithm or protocol, and users can vote with their governance token on interest rates as part of a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO).

The latest wave of innovations (sometimes referred to as DeFi 2.0) haven’t been very successful so far in tackling the limitations of DeFi 1.0. The landscape has evolved quite a bit since our 2021 report on the topic (see "Digitalization of Markets: Framing The Emerging Ecosystem," published Sept. 16, 2021), and new projects have been launched that claim to solve some of the issues with early DeFi protocols. While some of the proclaimed innovations, such as self-repaying and uncollateralized loans, initially expanded significantly, we understand that many projects failed because of flawed smart contracts or unsustainable tokenomics of the protocols (the economics or monetary policy of the token). In a few cases, the new DeFi protocols suffered significant reputational damage because of untrustworthy project founders or team members triggering panic sells and severe corrections in token values. These incidents also highlight the concentration risks of decentralized projects.

We expect anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) rules and customer protection will be key for regulators, since regulatory priorities for DeFi will likely be aligned with those of traditional lending. But the pseudonymous nature of the technology increases the importance of AML and KYC considerations. At the same time, the new, diverse, and often volatile digital assets used by these protocols, and the risks linked to the underlying code, heighten the risk for users.

The lack of regulation is hampering DeFi lending growth and increasing fragmentation, in our view. Regulators have prevented several attempts by established players to launch lending services. Coinbase’s DeFi yield product illustrates this point: it is available only to non-U.S. clients, because of the regulatory crackdown on DeFi lending-related offerings in the U.S. The SEC has put a halt to Coinbase’s plans to offer DeFi lending services in the U.S., although at this point it remains unclear whether the SEC sees these types of products as securities that must comply with federal securities laws. In the case of BlockFi, another crypto asset service provider, the SEC charged the company with failing to register its retail crypto lending product under the 1933 Securities Act. BlockFi settled the charge by paying a $100 million fine in February 2022 and communicated that it will try to offer an alternative yield product.

One key task is to determine which individuals or entities fall within regulatory perimeters. Regulations can’t directly stop the execution of smart contract code on blockchains that may not be located in their jurisdiction. Regulating the technology or software itself would stifle innovation. But there remains the question of whom--if anyone--to hold accountable for code weaknesses that lead to financial losses or other preventable outcomes.

True decentralization makes it tough to identify persons or businesses that can be held accountable through regulations. While regulators could identify the physical location when the smart contract was deployed on the blockchain to apply the governing law in the jurisdiction, the pseudonymity of the developers who deploy smart contracts and the code's protection as a form of free speech in the U.S. make this difficult. For instance, leading DeFi lenders such as Aave and Compound operate autonomous and trustless smart contracts without a central authority.

Because DeFi gives the financial responsibility--including asset custody and investments--back to users, we think some understanding of smart contracts is needed. What’s more, users of DeFi solutions must carry out proper research on the team behind a project, given the large share of code issues in the space as demonstrated by the amount of hacks in the past two years. We understand that there are some early on-chain attempts to reveal the identities of wallet owners, including developers who own contracts, and attempts to assign wallet scores that indicate fraudulent behavior. But platforms often rely on intermediaries, which could fall within regulatory perimeters. Even excluding the developers who initially created the code, protocols often rely on individuals or entities that provide funds for project development or provide user interfaces to make these protocols more scalable.

DeFi lending may need to be partly decentralized so that it can fall within regulatory frameworks. We have seen the emergence of permissioned access points to DeFi acting as regulated bridges to otherwise permissionless blockchain protocols (e.g., Compound Treasury). We think permissioned, regulated access points enable protocols and their users to comply with certain requirements (e.g., AML and KYC), thereby facilitating access to a larger number of users, including institutions. To be scalable, we think this compromise may be acceptable to lending platforms. Regulations could support the willingness of a broader range of actors to interact with DeFi lending platforms. We believe that larger players will be willing to consider compromises such as regulated, permissioned access points to comply with regulatory requirements.

It is hard to gauge the extent to which regulations could push more DeFi lending toward purely decentralized protocols, as we’ve seen with the emergence of DeFi 2.0. For activities remaining entirely decentralized, regulators may need to rely on other investigative tools to ensure compliance by persons and businesses in their jurisdiction with regulatory principles. Regulation would also require international coordination because of the borderless nature of DeFi. For regulators, DeFi lending may offer benefits versus traditional lending. Compared with regulating a traditional lender, regulating DeFi lending platforms will allow for the use of real-time and direct data accessible through blockchains. Supervisors may no longer need to rely on reporting by the platform, and a lot of the supervision may be automated--maybe even with the help of autonomous smart contracts as regulatory tools.

Cihan Duran, CFA | Alexandre Birry

Nonfungible tokens (NFTs) are not equal in intent or function. Regulations will need to reflect this. While some may ultimately be classified as securities, in other cases NFTs give rise to very specific regulatory considerations, including intellectual property.

Key Areas Of Regulatory Focus

Source: S&P Global Ratings.

Copyright @ 2022 by Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC. All rights reserved.

Trading in NFTs has become a material new market, despite the recent activity drop in line with the general "crypto winter". According to DappRadar, NFTs generated $12 billion in trades in the first quarter of 2022 (see chart above).

An NFT is a unique digital token. NFTs are typically immutable, which means they represent a certain piece of data that cannot be changed. However, alterable NFTs can also be created, which have uses as a method of encapsulating a certain type of dynamic data. As a medium of data exchange, NFTs are increasing in popularity and business use cases. An NFT token includes the data itself or reference to a location where the data is stored. A token identifier is generated to represent one or more copies of the information and is permanently assigned to the wallet address of the NFT holder. That token identifier/wallet link establishes a record of ownership when transferred on the blockchain. Like other crypto assets, NFTs are based on technical standards that allow their individual identification on the blockchain, even after potential multiple transfers. It’s the unique nature of the data inside an NFT that makes it accrue value.

A number of controversies in the past few months illustrate some of the risks. Examples include the sale of a fake Banksy NFT, prices artificially inflated by the seller also posing as a bidder for the same NFT, and a dispute between French luxury brand Hermes and an artist over the use of a line of iconic leather goods as digital tokens, to name just a few.

Regulations around NFTs are still playing catch-up with this rapidly growing asset class within individual jurisdictions. A largely harmonized global approach is even further away, despite the borderless nature of the technology and international ambitions of many projects.

Different functionalities may lead to different regulatory approaches. Certain NFTs are similar to digital versions of trading cards (e.g., baseball or Pokemon cards) and therefore may not require any specific regulation. Others for instance may generate revenues, either recurring (e.g., royalties on underlying content, sometimes embedded in an NFT’s smart contract) or in the form of expected one-off gains when (re)sold.

Some could be akin to securities. The U.S. SEC in early 2022 started investigating a certain type of fractional NFT, which represents ownership shares in the revenue associated with an asset (which differs from pure price appreciation of the asset). Some of these revenue-generating assets could meet the Howey test to be considered securities. In the EU, the Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation would apply to an NFT that grants its holder or issuer specific rights linked to those of financial instruments, such as profit rights, in which case they would be treated as “security tokens”. But the MiCA regulation otherwise explicitly excludes NFTs representing intellectual property (IP) rights, or the certificate of authenticity of a unique physical asset, for instance, for which a bespoke regime may be considered.

Unique features may require new or updated regulations. Beside the classification as security or not, anti-money laundering, and other typical regulatory considerations in the crypto space, NFTs entail a number of unique legal challenges, including:

IP ownership: the uncertainty over who owns the IP underpinning an NFT can lead to dispute. In November 2021, for instance, Quentin Tarantino announced a planned sale of Pulp Fiction NFTs. Miramax, the studio, filed a suit within days.

Trademark and copyright infringement: NFTs using trademarks or copyrighted materials without authorization have led to a number of lawsuits.

Authenticity: digital art can be instantaneously and easily replicated, making it sometimes harder to ascertain that a particular version is the original one.

How the NFT is intended to be used and how it is marketed will likely be key considerations. Using the example of the music industry, a music NFT doesn’t necessarily mean ownership of royalties on the underlying content. In many cases, it just constitutes a form of patronage. But some marketplaces do sell music NFTs that entitle owners to receive royalties every time a song is played--and these may be classified as securities according to crowdfunding regulation in the U.S.

NFT popularity may grow exponentially with the emergence of the metaverse. NFTs allow an on-chain based transfer of assets in the virtual world. The fully virtual and still very fluid nature of the metaverse amplifies the existing regulatory challenges surrounding NFTs.

Platforms and marketplaces will likely be held accountable. To achieve scale, NFTs already rely on service providers for the different stages of their lives, from minting to marketing and selling. These counterparties will likely be responsible for clearly defining the NFTs they mint--e.g., whether a security or other type of asset--and this will determine which regulatory or supervisory framework they fall under, if any. But heterogeneous frameworks across jurisdictions may complicate matters.

Regulations won’t immunize different corporate sectors from new challenges. Corporates in the art sector or whose brand strength is a key driver of sales are among the most directly affected by these regulatory and legal considerations. But regulations are unlikely to stave off new forms of competition.

Clearer rules could give rise to new revenue streams. Understanding these rules for incumbents is not just a defensive play; it could, in some cases, open growth avenues as a new asset class emerges. A clearer regulatory framework for NFTs could also pave the way for entire new industries, in our view, with entrepreneurs building metaverse projects, to name one prominent example.

Cihan Duran, CFA | Prateek Nanda

Regulations for centralized and decentralized crypto asset exchanges differ substantially across jurisdictions, and decentralized exchanges remain unregulated for now. We see regulations evolving toward a broader coverage of exchanges, with consumer protection a key goal.

Exchanges that investors use to access and trade crypto assets can be centralized or decentralized. Both play an equally important role, but their functionality, user interface, and regulatory coverage differ significantly. Centralized exchanges are key for on-ramp and off-ramp of fiat money, which can then be transferred to web3 wallets and swapped to other tokens through decentralized exchanges.

A centralized exchange (CEX) is a third-party intermediary acting as an agent, matching trades between buyers and sellers and earning fees through that process. Clients of a CEX need to deposit their fiat money to trade with crypto assets. As such, they entrust their assets to a third party, which is akin to a traditional online broker. According to CoinMarketCap, there are about 300 CEXs worldwide--some regulated and some not. Binance is the largest CEX globally with double-digit billions of trading volumes per day and licenses in many countries.

A decentralized exchange (DEX), on the other hand, is not a legal entity with legal obligations and does not act as a custodian for client assets. Typically, it is owned and governed by token holders, who are often users of the exchange. Users retain sovereign ownership of their assets via their personal wallets and can trade them peer-to-peer through smart contracts on the specific blockchain that underpins the DEX, without intermediaries. Most DEXs do not rely on the usual order book model to facilitate trades or set prices. Instead, they use liquidity pools, whereby buyers and sellers swap any two tokens seamlessly via the underlying liquidity pool provided to the DEX. Unlike CEXs, DEXs have no power over which tokens can be traded over their platform, and anyone can create a liquidity pool that investors can access to buy or sell a token.

CEXs are typically regulated by existing national competent authorities (NCAs) in the markets where they operate. For instance, Coinbase and other U.S.-based CEXs are regulated as money service businesses and have licenses to engage in money transmissions. Management-run crypto exchanges such as Coinbase can be regulated because of their jurisdictional locations and human-led operations, as opposed to algorithmic and decentralized decision-making. They need to comply with strict know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) laws, like other regulated financial institutions. Other countries have legislated to ban CEXs entirely. For example, China has a de facto ban on crypto exchanges because the government prohibited cryptocurrency transactions in September 2021.

Conversely, DEXs are not currently regulated. This is largely because they are not owned or operated by an entity or are not management-run, which would make natural persons or legal entities liable under traditional law. Uniswap is a good example and one of the best-known decentralized autonomous organizations (DAO), which is the core of the protocol's governance structure. The DEX's underlying smart contracts, which enable trading, operate autonomously and are accessible by anyone. Also, it is currently very difficult to implement KYC and AML/CFT checks, as pseudonymous wallet owners can directly connect to the DEX platforms.

Licensing requirements and applicable regulations for CEXs are relatively well defined in most countries. In the U.S., a CEX needs to comply with multiple financial services and consumer protection laws depending on the products it offers; for example, the Bank Secrecy Act and USA Patriot Act. Coinbase, for example, is registered with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) as a money services business. It also needs to implement an AML/CFT program, stick to records retention standards, establish a risk organization to ensure compliance with all applicable laws, and submit regulatory reports to the authorities. Like other traditional financial custodians, Coinbase is regulated by the New York Department of Financial Services and subject to capital requirements. In the U.K. and EU, CEXs must register with the NCAs and comply with KYC, AML/CFT reporting, and customer protection laws. These still differ across each of the countries.

The activities and products offered by CEXs may fall under different regulatory regimes. Innovation may make such determinations challenging for regulators. For instance, in September 2021, Coinbase received notice of a possible enforcement action from the SEC related to its interest-earning product called Coinbase Lend, because of the SEC’s views that Coinbase’s role as an exchange, combined with how the product may be constructed, constituted a security. In some countries, cryptocurrency derivatives were also banned because the volatility of such instruments could harm retail investors. Consumer protection will likely remain a key goal of policymakers when regulating CEXs, balanced against the need for innovation.

Regulators face a more arduous task with DEXs because of their borderless and autonomous nature. In September 2021, the SEC was reportedly in talks with Uniswap Labs, the lead developer of the Uniswap DEX, to better understand how the exchange’s services are used and marketed with a view to defining a stance on the broader topic of decentralized finance (DeFi). DEXs play an integral role in DeFi, and cover about 50% of the market capitalization of DeFi categories (see chart below). We believe that regulatory frameworks currently don’t cover pure DeFi activities, including DEXs. The EU’s Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) regulation explicitly excludes DeFi from its upcoming rulebook, which will most likely go live in 2024. The U.S. is aligning views across its NCAs under the President’s Executive Order, which was released in March 2022. Given the size of traded volumes on DEXs and the potential growth of the DeFi sector, we expect policymakers will try to define a framework to have a minimum level of oversight over DEXs.

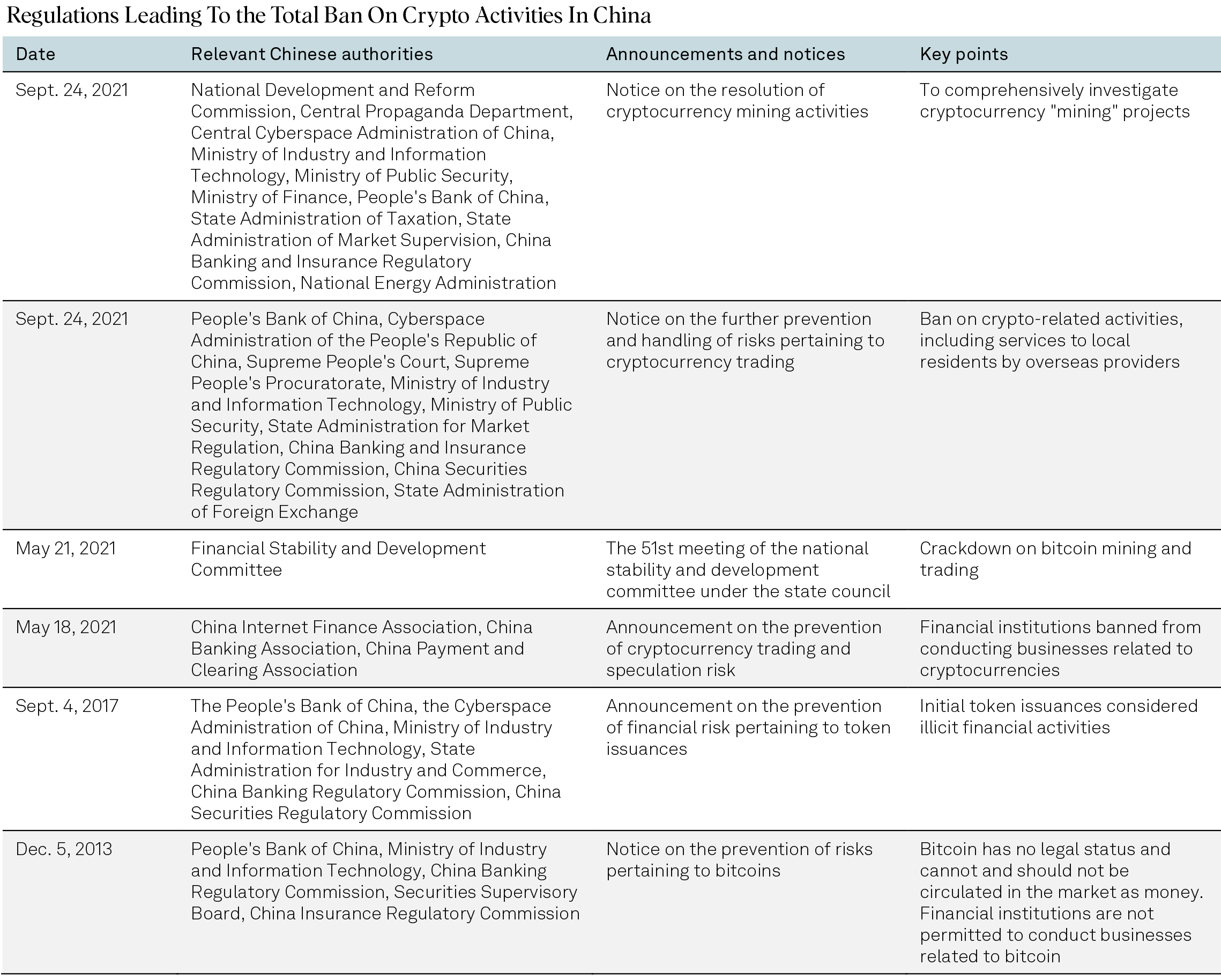

China's ban on all crypto activities is unlikely to be reversed. Yet, while it has had a significantly adverse impact on the attractivity of crypto assets in China, there is evidence that bitcoin mining activity in the country is returning.

China officially banned crypto activities in 2021. The warnings came as early as 2013 and the regulatory intensity rose substantially last year as the crypto sector grew and valuations increased rapidly. The regulatory stance is among the strictest in the world, and Chinese authorities cited national security and social stability considerations in a joint notice delivered by 10 ministries, regulators, and other national bureaus in September.

The authorities view crypto activities as illicit financing activities. These activities are broad and include crypto exchanges, conversion, trades, derivatives transactions, and related pricing and information services. The ban also includes services to local residents by overseas providers through the internet. Furthermore, financial institutions are not permitted to provide related services. Shortly after this notice, several crypto asset exchanges announced their exit from the China market, with some giving a December deadline for customers to close their accounts.

Penalties for rule breakers could be heavy. The ban is not a surprise. In 2013, Chinese authorities warned that cryptocurrencies are not considered legal tender and should not be in circulated in the market. Initial coin offerings were also deemed illegal financing activities in 2017. Given the high-level government attention and seriousness of language used in the rules, we believe penalties for noncompliance will be severe.

Bitcoin mining stopped entirely in China after being banned in May 2021, but there is evidence that it is returning. China’s bitcoin mining hashrate--essentially the computing power of the network--appears to have dropped to 0% on a global comparison in the months following the ban, according to data from the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (see chart below). However, the data shows that the bitcoin hashrate in the country significantly increased again in September 2021 and has remained high--although substantially lower than before the ban--at about 20% of the global total (see chart). It appears that some bitcoin miners may be using virtual private networks (VPNs) to obfuscate their location, and therefore the source of hashrate power.

Cihan Duran, CFA | Markus Schmaus

We expect that the EU's Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) regulation for the 27 member states may create a more transparent and uniform environment, build greater trust for investors, and simplify the operations of service providers across the EU.

On June 30, 2022, lawmakers in Europe reached a provisional agreement on an EU-wide rulebook for investments in crypto assets and crypto asset service providers (CASP) as part of its “Digital Finance Package”. The package lays out a strategy for digital finance and retail payments in Europe, including a pilot regime for market infrastructures that allows the use of distributed ledger technologies in a sandbox environment for trading and settlement of financial assets. The package also introduces a regulation to set standards for the digital operational resilience of companies and to regulate crypto assets. MiCA covers the latter part. It aims to undo legal and regulatory fragmentation across the nations of the EU-27 and to streamline existing rules. Its policy goal is to foster investments and innovation in the blockchain industry and increase transparency around crypto assets, while ensuring consumer and investor protection and preserving financial stability in the EU. MiCA introduces a comprehensive framework of rules for crypto assets, including a new licensing system for issuers of nonregulated crypto assets (e.g., stablecoins), conduct rules and requirements for CASPs, and rules to protect consumers and investors, among others.

Until the MiCA regulation comes into force, the current policy landscape remains a patchwork across the EU. Some overarching rules set at the EU and supranational level have steered policymaking at the national level, but they are not specific enough to have created a level playing field across member states. The guidance for virtual asset service providers (VASP) from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in 2019 defines rules around the exchange of client data between VASPs when funds are transferred. What’s more, the implementation of the Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5) in 2020 requires VASPs operating in EU member states to register with NCAs and follow strict know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) standards for cash-to-crypto transactions and vice versa. The FATF guidance and AMLD5, however, are ambiguous enough that member states have the freedom to interpret rules differently. This has led to the emergence of legislative differences that increase the complexity and costs to operate across Europe.

As a result of the ambiguity of existing rules, but also because of the diversity of NCAs in EU member states, policymakers and regulators have a different stance toward crypto assets and the laws governing them. For example, Portugal is seen as one of the most crypto-friendly countries for investors in Europe because of its modest cryptocurrency taxation, while Malta has attracted a number of startups operating in the blockchain industry in recent years because of its less stringent licensing and registration requirements.

MiCA aims to replace national crypto policies in the EU, with binding legal force for all member states when approved by the legislative bodies. This will likely harmonize rules and reduce complexities, legal uncertainties, and costs for cross-border operations of CASPs. One outcome of this, for example, is that it may allow CASPs to operate in multiple EU countries. This should lead to a level playing field for CASPs and less regulatory arbitrage in the EU. That said, we understand MiCA may also tighten some rules for CASPs, such as capital requirements and standards for issuing project-linked tokens. This may increase compliance costs but should improve the quality and robustness of CASPs.

We also understand that the new regulation will aim to provide clear definitions of covered types of crypto assets and CASPs, providing more legal certainty. There are currently no agreed definitions or industry standards, which leads to misunderstanding and confusion in the market. MiCA may introduce granular crypto asset-related definitions and give more clarity on the classification and treatment of crypto assets and covered companies by defining covered tokens and CASPs. That said, whether a token is a crypto asset (MiCA) or financial instrument (MiFID II) may need to be clarified in individual cases and most likely handled in the whitepapers that token issuers may be required to release under MiCA. We understand that central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and security tokens do not fall under the MiCA regulation. The European Council release in June 2022 confirmed that nonfungible tokens (NFTs) will be excluded from the scope unless they fall under existing crypto asset categories. By the end of 2023, the European Commission will be tasked with assessing the risks around NFTs and considering whether a framework is required to address the risks related to this new market.

The latest MiCA proposal includes a particular focus on stabelcoins. This reflects policymakers' concerns about potential systemic risks from stablecoin issuers. The fall of the third-largest algorithmic stablecoin, TerraUSD, in May 2022 is only accelerating regulatory scrutiny, in our view. We understand that the proposal requests "stablecoins issuers to build up a sufficiently liquid reserve, with a 1/1 ratio and partly in the form of deposits". Also, stablecoins will be supervised by the European Banking Authority (EBA).

We understand that there has been less regulatory focus to date on decentralized finance (DeFi), which we further understand is not within the scope of the MiCA proposal. The European Commission will likely report on DeFi during 2023. It is potentially difficult to regulate DeFi projects because of their decentralized nature, meaning they do not have a central authority or person. Developers who launch projects and tokens on blockchains such as Ethereum via smart contracts that run on their own outside human control are not bound by national regulation and often remain anonymous. That said, not all such projects are decentralized given their heavy reliance on a developing team and the owner(s) of the smart contract. Common controls and clearer standards may emerge over time to ensure that investors and consumers can better understand the risks inherent in particular projects.

Related to DeFi, policymakers have also agreed on amendments to the Transfer of Funds Regulation (TFR), which defines rules for money transfers by requesting that intermediaries collect and share data on transactions. The revision requires CASPs to share information on payer and payee of unhosted wallets between one another to ensure full traceability of transactions. We believe that some CASPs may not be in a position, or may be unwilling, to collect the required data considering the complexities and associated costs. TFR could cut ties of European CASPs with unhosted wallets, which are the entry point to DeFi products. This may affect European competitiveness in this field. Users might move away from European CASPs and use foreign and unregulated solutions to connect to their wallets to transfer funds.

MiCA could, in our view, strengthen investor trust in crypto assets, and may lead to broader acceptance by institutional investors who have so far shied away from this asset class because of regulatory uncertainty. We see increased interest from global policymakers in either setting new, or redefining existing, standards and frameworks for the crypto industry. The executive order on ensuring responsible development of digital assets by the U.S. president is one indication that it is not just the EU aiming to find a structured regulatory framework. We expect regulation to remain fluid and evolving in the future as well, considering the global reach of some providers and DeFi considerations that require an international regulatory approach.

Cihan Duran, CFA | Alexandre Birry

At present, oversight of crypto activities in the U.K. focuses mainly on anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing, while customer protection is attracting increasing scrutiny. In February 2022, the U.K. government confirmed plans to bring the marketing of crypto assets--including exchange and utility tokens (bitcoin and ether) and stablecoins--within the scope of financial promotion rules. Prior to this, authorities had already banned the sale of crypto derivatives to retail clients and brought crypto exchanges and wallets within the scope of financial crime rules. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has also already issued a number of warnings. In March 2022, for instance, it issued a “Notice to all FCA-regulated firms with exposure to crypto assets”, just after EU regulators issued warnings to consumers for its regulatory perimeter (see "Read more").

Regulatory authorities are finding it challenging to meet the registration demands of crypto-related firms. In March 2022, the FCA extended a temporary licensing program for a number of firms whose applications had not been fully processed. Registration is typically required to comply with the updated money-laundering directives introduced in January 2020, which brings crypto assets into scope. In addition, if a firm looks to offer services for digital assets that confer rights such as ownership, repayments, or entitlement in future profits, such assets are likely to be classified as a specified investment under the Regulated Activities Order (RAO).

In the global competition to remain a growing and innovative financial hub, the U.K. has strong cards to play. Compared with the EU and the U.S., it benefits from a simpler policymaking structure, with fewer policymaking bodies involved in the process of establishing a regulatory framework for crypto assets. Also, regulatory bodies have won a good reputation in their ability to deal with technological innovation. The FCA sandbox initiative, for instance, involves a “semi-authorization” process through which firms can test their products in a limited and safe environment, under the oversight of the FCA. This process can offer significant benefits for early-stage firms.

The government has publicly stated its ambition for the U.K. to become a global crypto asset technology hub. To support this ambition, it aims to propose “a staged and proportionate approach to regulation” and in April 2022 it announced a package of measures and ideas. This announcement follows a consultation on the topic and call for evidence initiated in January 2021 and includes:

Bringing stablecoins within regulation to prepare for their recognition in the U.K. as a form of payment;

Introducing a “financial market infrastructure sandbox”;

Establishing a Crypto Asset Engagement Group between policymakers and the industry;

Exploring ways to enhance the competitiveness of the U.K. tax system for crypto assets; and

A research program to explore the feasibility and potential benefits of using distributed ledger technology (DLT) for sovereign debt instruments.

The first legislative phase will focus on stablecoins. According to HM Treasury (HMT), the government finance ministry, stablecoins “have the capacity to potentially become a widespread means of payment, including by retail customers, driving consumer choice and efficiencies”. The government intends to amend existing legislation on electronic money and payments as soon as possible. It also noted the need to make arrangements to be able to deal with risks related to a systemic stablecoin failure. At the same time, the possibility of a U.K. central bank digital currency (CBDC) remains in the research phase, with the Bank of England partnering with other key central banks across the globe in their studies.

Other proposals remain very high level on key areas. For instance, there are no recommendations for decentralized finance (DeFi) or nonfungible tokens (NFTs). HMT intends to consult later in 2022 on some of the other key topics. We see a parallel with the EU's Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) regulation, which also stays largely silent on DeFi and NFTs.

The sandbox approach can offer benefits both for innovative firms and regulators. The U.K. policymakers have already leveraged this tool for some time. The proposed financial market infrastructure sandbox should be operational in 2023. It would allow firms to experiment with the use of DLT, while allowing policymakers to understand what changes are required.

Policymakers will have to move fast if they want to meet government’s digital ambitions for the U.K. They will likely keep an eye on the EU, which has recently agreed on the MiCA regulation and is now going through formal adoption (even if the rules will only start to apply 18 months later). MiCA will provide greater regulatory certainty, despite some areas of greater restriction for market players. Given the fluidity of the ecosystem and international rules, one of the government’s goals is to “ensure sufficient flexibility is built into the U.K.’s regulatory framework”.

The U.S. is sprinting to catch up to Europe and Asia as it works to develop a broad legal framework for regulating blockchain technology and digital assets. We expect active debate around comprehensive legislation in the U.S. Congress over the next 12-18 months, after President Biden’s executive order compressed the timeline.

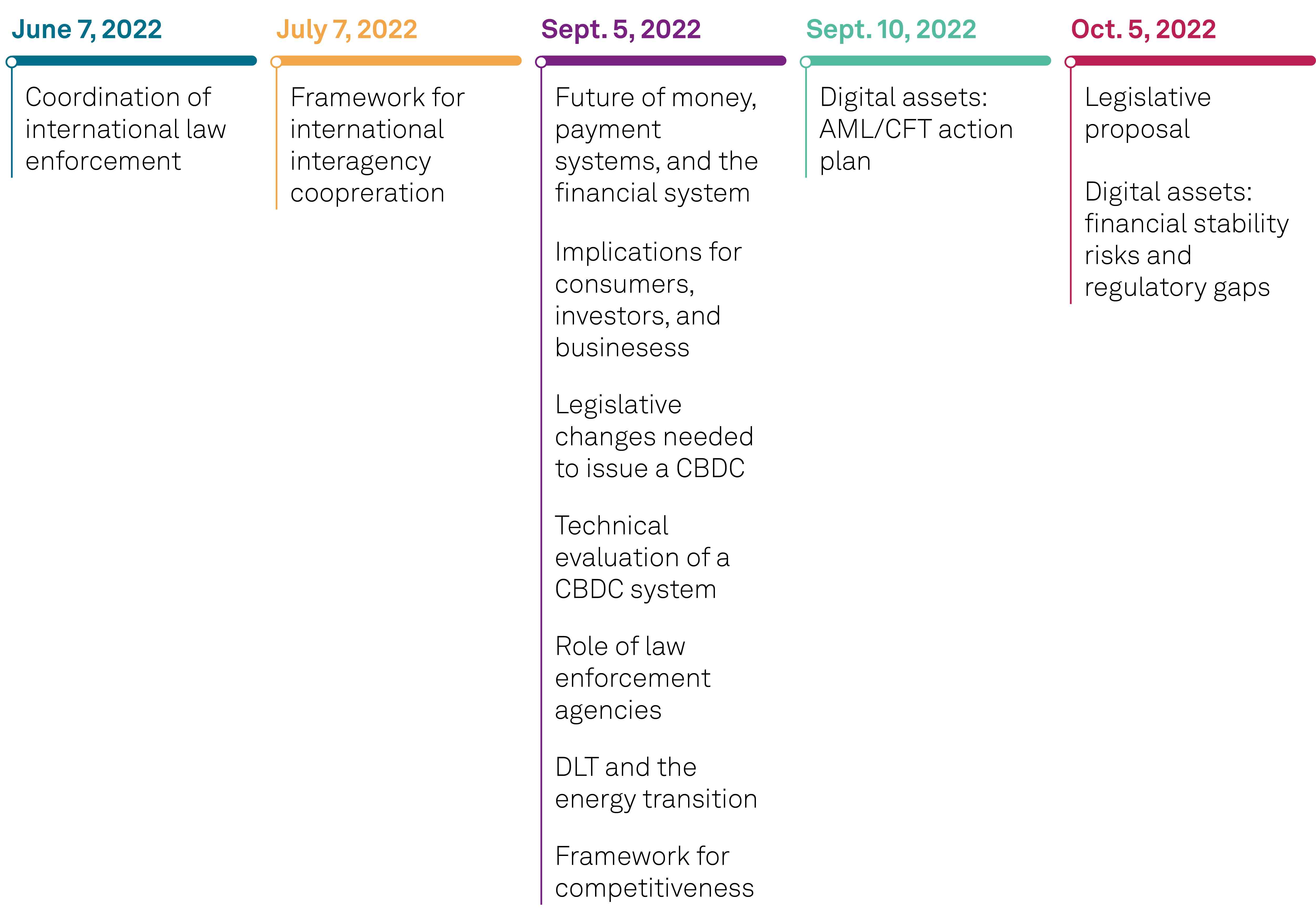

Executive Order On Ensuring Responsible Development Of Digital Assets

AML/CFT--Anti-money-laundering/combating the financing of terrorism, CBDC-- Central bank digital currency. DLT--Distributed ledger technology.

Source: S&P Global Ratings.

Copyright @ 2022 by Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC. All rights reserved.

Sources: Executive Order on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets (March 2022), S&P Global Ratings.

U.S. lawmakers and regulators are taking steps to address regulatory gaps in the crypto industry until Congress passes legislation that establishes a broad regulatory framework. The first U.S. laws to target digital assets were introduced in the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act, which was signed into law on Nov. 15, 2021. It required “brokers” to disclose information about their customers for tax reporting purposes, and businesses to report (digital asset) transactions worth more than $10,000 to the IRS to help detect money laundering. Attempts at consensus building around a broad regulatory framework will continue this year, with blockchain and digital assets increasingly receiving the attention of U.S. lawmakers. Several legislative proposals have already been drafted in the U.S. Congress; most notably, a bill for comprehensive legislation that was introduced by two senators in June 2022. Meanwhile, regulators are taking steps to reign in the crypto industry through enforcement actions (for example, see “CFTC Charges 14 Entities”), and the SEC has proposed an amendment to rules for alternative trading systems (ATS) that could bring digital asset exchanges directly into its jurisdiction.

President Biden has called for a “whole-of-government” approach to understanding regulatory issues. The development of blockchain and digital asset laws and regulations in the U.S. remains in a discovery phase, and President Biden’s Executive Order on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets should advance the debate over key issues in the coming months. The strategy outlined in the executive order includes 12 key action points, which broadly address: blockchain developments; digital assets; central bank digital currencies (CBDCs); payment systems; financial stability; protections for consumers, investors, and businesses; anti-money laundering/combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT); environmental risk and opportunities; and technological infrastructure. The executive order continues the cross-government approach that produced the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets (PWG) report on stablecoins in late 2021, which included legislative recommendations. This whole-of-government approach could conceivably lead to consensus building across a broad set of issues, with the secretary of the treasury, the attorney general (AG), and the director of the Office of Science and Technology policy leading the effort. However, it is unclear when we will see comprehensive legislation signed into law, with a high bar for broad agreement in both chambers of Congress.

The SEC occupies the headlines, but regulators across the federal government work to address blockchain and digital assets within their respective jurisdictions. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRB), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) jointly announced at the end of 2021 that guidance related to digital assets for banking organizations (on custody services, exchange services, collateralized lending, stablecoins, and bank balance sheets) would come throughout 2022, and would provide clarity for incumbent financial institutions that mostly remained on the sidelines as the crypto industry exploded over the past two years. We also expect more clarity around the priorities for rule changes from regulators. The executive order encourages the chairs of the SEC, Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), FRB, FDIC, and OCC to each consider how they can address the risks of digital assets within their respective jurisdictions and whether additional actions are needed. The process of evaluating jurisdictional rule changes across U.S. regulatory agencies will likely be facilitated by a report that is due Sept. 5, 2022, through the executive order. This report will be prepared by the secretary of the Treasury in consultation with the secretary of labor and the heads of other relevant agencies where appropriate (i.e., those agencies previously mentioned, as well as the Federal Trade Commission and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau) and will include proposed regulatory and legislative actions that protect consumers, investors, and businesses, and support increased access to financial services. In the meantime, we expect the SEC, CFTC, and regulators within the Treasury to continue to utilize enforcement actions.

Cross-government assessments from President Biden’s executive order potentially broaden the scope of future legislation. The executive order takes broad aim at the regulatory challenges posed by blockchain technology and digital assets, and several action points that come due over the next four months will include regulatory and legislative recommendations. Until recently, most legislative proposals from Congress have been relatively narrow. Work from the executive order could help bring several issues into one piece of legislation, and it expands the scope to include blockchain infrastructure and climate policy issues.

The first report from the executive order was led by the AG and outlines a strategy for strengthening the coordination of international law enforcement (see “How To Strengthen International Law Enforcement Cooperation For Detecting, Investigating, And Prosecuting Criminal Activity Related To Digital Assets”). On July 7, 2022, the Treasury secretary, in consultation with the heads of other relevant agencies, provided a framework for international interagency cooperation that coordinates global compliance and promotes international standards for digital assets and CBDC technologies (see "Fact Sheet: Framework for International Engagement on Digital Assets"). Several more assessments will come due on Sept. 5, 2022, and these will evaluate: the future of money, payment systems, and the financial system; the implications for consumers, investors, and businesses; legislative changes needed to issue a U.S. CBDC; a technical evaluation of a U.S. CBDC system; the role of law-enforcement agencies; blockchain technology and the energy transition; and a framework for U.S. economic competitiveness. By Sept. 10, 2022, the Treasury secretary, in consultation with the heads of other relevant agencies, must develop an action plan that addresses the AML/CFT issues related to digital assets. The work stemming from the executive order will culminate in a legislative proposal led by the AG in consultation with the Treasury secretary and the chair of the FRB, and an assessment of financial stability risks and regulatory gaps from the Financial Stability Oversight Council, each due by Oct. 5, 2022.

Following President Biden’s executive order, the pressure on lawmakers has been turned up, and we expect efforts to increase in both chambers of Congress. We expect U.S. lawmakers will work to build consensus ahead of the legislative proposals that flow from the executive order to maintain more control over the shape of future legislation. With that in mind, it was unsurprising that a Republican senator and a Democratic senator announced their partnership in developing a broad framework for regulating digital assets in late March 2022, shortly after the executive order was signed. The partnership appears promising given the prominent positions of the two senators, who released their broad legislative proposal, the Lummis-Gillibrand Responsible Financial Innovation Act, in June (see “Lummis, Gillibrand Introduce Landmark Legislation To Create Regulatory Framework For Digital Assets”). The proposal addresses the ambiguity around regulatory jurisdiction over digital assets (e.g., CFTC or SEC), establishes a regulatory sandbox to support innovation, establishes requirements for stablecoins, and creates a framework for taxation, among other things. How well the senators whip up support will be something to monitor. We expect regulatory proposals and lawmakers’ views will remain active in crypto headlines over the next 12-18 months.

While regulatory developments and policy stances vary significantly, most countries have some form of crypto regulations, either in place or proposed. However, a handful of countries have been more crypto-friendly than most in terms of regulations surrounding crypto assets, policy stance, and tax treatments of these investments. At present, the list includes Switzerland, Singapore, Australia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and El Salvador, and new joiners such as the Central African Republic. There are material differences between these crypto-friendly countries, but most of these are eager to attract crypto and blockchain players and become hubs for the industry. And most of them generally have rules and supervisory functions in place to ensure that crypto asset service providers comply with anti-money laundering (AML) and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) obligations.

The material losses caused by the recent market rout appear to have toughened the regulatory resolve of even some of the more crypto-friendly policymakers. But we believe that as the market thaws, some differences in regulatory stances will endure.

Switzerland is a very appealing country for cryptocurrency and blockchain-related projects, attracting many crypto startups and large investments. The crypto activities in Switzerland--particularly the town of Zug, nicknamed “Crypto Valley”--make it a hub for projects from all over the world, including the prominent Ethereum Foundation. About 1,000 crypto startups operate in Switzerland, almost 50% of which are based in Zug. On a per capita basis relative to other nations, we estimate this to be one of the key crypto hubs. Switzerland's regulators have actively supported a legal framework that encourages the country’s crypto hub status. Lawmakers have even legalized tax payments with cryptocurrencies in some regions; for example, the Canton of Zug is accepting bitcoin and ether as means of payment. What’s more, the City of Lugano has partnered up with stablecoin issuer Tether to establish cryptocurrencies as a means for everyday transactions, including tax payments. Key regulatory developments include:

Switzerland’s federal government, Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA), and central bank all recognize the potential benefit of technologies surrounding crypto assets and blockchains. Of note, in 2020, the Parliament passed distributed ledger technology (DLT) legislation (the DLT Act) to address regulatory gaps, which included the creation of new licenses that are tailored to crypto asset service providers and will provide more opportunity for innovation.

The central bank has been evaluating the viability, pros, and cons of a central bank digital currency (CBDC) for digital settlements. The FINMA’s published guidelines provide some clarity on its treatment of initial coin offerings (ICOs) with a focus on the economic purpose of the tokens. It established a sandbox for innovation in 2019, where crypto businesses and fintechs enjoy simplified regulatory requirements to test their business model.

SIX Digital Exchange received regulatory approval for its digital asset exchange application in 2021. This is likely to attract even more digital asset investments to the country.

While Switzerland generally considers cryptos to be digital assets, some regions do accept bitcoins as legal tender.

Switzerland does not have capital gains taxes, but it does have income taxes on crypto-related activities such as crypto mining.

Singapore regulates all crypto activities with respect to their purpose rather than the technology, and remains very attractive for crypto start-ups and investments because of its regulations and favorable tax treatment of capital gains. While the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has recently toughened its tone on crypto assets and promised a tightening of regulations to protect retail investors from fraud, we do not expect the country to move away from its crypto-friendly nature considering existing regulations. That said, we acknowledge some emerging uncertainties on the regulatory direction. Key crypto developments are as follows:

The MAS classifies cryptocurrency as property, not legal tender. The MAS regulates and licenses digital exchanges and we understand that it does not intend to ban cryptocurrency trading activities.

We believe a key objective of the crypto regulatory framework is to protect both the country’s reputation as a global financial center and its consumers, while preventing illicit activities such as money laundering and terrorism financing.

Singapore does not levy a tax on long-term capital gains for individuals or when cryptocurrencies are used to pay for products and services. However, for companies regularly transacting in cryptocurrencies, these gains could be considered as taxable income.

Singapore’s Securities and Futures Act of 2001 regulates initial public offerings of digital coins.

In recent years, several crypto exchanges, startups, and blockchain entities based in India have decided to move to Singapore amid regulatory uncertainty in India.

Australia is establishing itself as a relatively progressive and stable destination for blockchain and crypto asset operations. Digital exchanges have been around since 2017, making Australia an industry leader.

Australia licenses crypto asset service providers and considers cryptocurrencies as financial assets under its securities law.

The Australian Transactions and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC)’s Digital Currency Exchange (DCE) requires the enrolment of digital currency exchanges to generate financial intelligence.

Australia classifies cryptocurrencies as legal property, not money.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has no immediate plans to issue a retail CBDC, but it has been involved with projects to explore a wholesale CBDC.

The tax consequences of cryptocurrency transactions are like a barter arrangement. Trading gains are subject to capital gains tax, as is the case in many other countries.

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) has provided guidelines on the treatment of tokens, while focusing on their technology-neutral functionalities.

The UAE is vying with other crypto-friendly countries to attract large crypto investments and become a global crypto hub.

Abu Dhabi Global Market (the Emirate's international financial center) has implemented a comprehensive framework to regulate virtual asset activities (see for instance the "Guidance – Regulation of Virtual Asset Activities in ADGM", published Feb. 24, 2020).

The Financial Services Regulatory Authority’s (FSRA’s) regulatory framework is focused on consumer protection, safe custody, technology governance, disclosure/transparency, and market abuse.

Dubai has also implemented friendly regulations applicable to virtual asset services provided in the Emirate and has established the Dubai Virtual Assets Regulatory Authority (VARA, see "Law No. (4) of 2022 Regulating Virtual Assets in the Emirate of Dubai").

VARA's objectives include, among others, the promotion of the Emirate as a regional and international hub for virtual assets and related services.

El Salvador is one of the most well-known crypto-friendly countries since it passed a law in 2021 that made it the first country to accept bitcoin as an alternative legal tender. However, bitcoin usage for everyday transactions through the “Chivo Wallet” has been low so far and is mostly concentrated among the more-educated demographic. According to research from the National Bureau of Economics, 60% of the approximately 1,800 surveyed households have downloaded the wallet, and only 20% continued to use it after receiving the $30 sign-up bonus for the wallet application.

Businesses are required to accept bitcoin for all payments. Two-way bitcoin-to-dollar convertibility is provided at the banks.

Because of its legal tender status, there is no income or capital gains taxes on bitcoin in the country.

El Salvador plans to build a “bitcoin city” to attract crypto investments and maintain its status as a cryptocurrency hub.

The government announced in November 2021 that it will issue a $1 billion bitcoin-backed bond. Officials stated that half of the bond issuance would be used to buy bitcoin and the other half would be used to build a geothermal plant in the bitcoin city for bitcoin miners. However, the bond issuance is on hold because of uncertain market conditions.

Altcoin. Any cryptocurrency that can serve as a substitute for bitcoin.

Automated market maker (AMM). An AMM removes the need for an intermediary to manually quote bids and ask prices in an order book and replaces it with an algorithm.

Bitcoin Lightning Network. A protocol designed to address scalability issues on the Bitcoin network by taking transactions off the blockchain to promote transaction speed and efficiency.

Blockchain. A type of distributed ledger technology that groups data into blocks that when verified by members of the network are linked together to form the blockchain.

Central bank digital currency (CBDC). A digital token representing sovereign fiat currency.

Centralized exchange (CEX). An exchange that processes transactions as an intermediary (“middleman”) and requires full custody of users’ funds.

Crypto asset. A digital asset that can include cryptocurrencies or any other digital token (e.g., nonfungible tokens), with transactions recorded using distributed ledger technology.

Crypto asset service provider (CASP). Any person whose occupation or business is the provision of one or more crypto asset services to third parties on a professional basis (as defined by the EU's Markets in Crypto Assets regulation)

Cryptocurrency. A digital asset intended to be used either as a medium of exchange or store of value with transactions recorded using distributed ledger technology.

Cryptography. Broadly encompasses techniques that secure and encrypt information.

Cold wallet. A digital wallet that exists off the internet.

Decentralized application (dApp). A front-end application that runs on decentralized peer-to-peer networks such as Ethereum and enables interactions through smart contracts.

Decentralized autonomous organization (DAO). DAOs are rules encoded by smart contracts on the blockchain controlled by token holders who can vote on decisions.

Decentralized finance (DeFi). Distributed ledger technology-based financial services without traditional intermediaries and central authorities.

Decentralized exchange (DEX). A DEX enables trading with a liquidity pool and direct swapping of tokens without the need for a centralized intermediary.

Digital asset. Any asset that exists in a digital form.

Digital wallet. A place to store digital assets with some level of security.

Distributed ledger technology (DLT). A system of record that is shared and stored across a network of participants (nodes). Blockchain is a type of DLT.

Ethereum. A popular blockchain platform that has smart contract capabilities.

Flash loan. An unsecured loan originated and repaid instantaneously on a distributed ledger technology platform within a single transaction (e.g., typically used for arbitrage).

Hard fork. A change to a blockchain network's protocol that results in two separate blockchain networks, forcing all nodes to upgrade to the latest version of the protocol's software.

Hash rate. A proof-of-work blockchain network's total capacity to validate exchanges.

Liquidity pool. A pool of digital assets used to facilitate trading and lending, designed to eliminate the need to identify a counterparty.

Markets in Crypto Assets (MiCA). Upcoming EU regulation introducing a harmonized and comprehensive framework for the issuance, application, and provision of services in crypto assets across the 27 member states.

Nonfungible token (NFT). A unique digital token that cannot be replicated.

Node. One of several dedicated computational engines, stores of memory, and broadcasting sites on a distributed ledger technology network.

Nonce. A number that can be used just once in a cryptographic communication in a distributed ledger technology network to guarantee unique exchanges.

Oracle. Service providers that collect and verify off-chain data to be provided to smart contracts on the blockchain in a trustless way/without the need to rely on a third party.