Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

23 Apr, 2020

Well before the oil price rout caused by the coronavirus pandemic, commentators and shareholders were calling on Big Oil to make step-out energy transition acquisitions.

Now, with economies in lockdown and corporates fighting to survive, the oil sector’s incremental move into new energy looks over-cautious.

As the value of their fossil fuel assets tumbles, the coronavirus lays bare these companies’ exposure to a world of massively smaller oil and gas demand, offering a glimpse of the EV revolution to come.

And environmental groups are keeping the pressure on oil companies during the crisis even as they cut capital spending, arguing that once economic activity picks up again, new investment should be channeled into stable renewable energy jobs.

In the last three years, global oil and gas companies have branched out into new sectors, ramping up investments in the power sector, low-carbon technologies and mobility, as they respond to intensifying climate campaigning that has also spurred activism among their traditional investors.

The new strategies on display raise questions about how far – and how fast – the giants of fossil fuel production are willing to go in their pursuit of decarbonization.

The start of 2020 saw France’s Total fly out of the energy transition blocks, winning Europe’s largest EV charge point contract in the Netherlands, partnering Groupe PSA in a pilot EV battery facility and taking a 2 GW Spanish solar position.

Others are adding to incremental gains in renewables. Lightsource BP, which is 43% owned by BP, has just closed financing on a 250 MW Spanish solar portfolio while late last year Shell bought out floating wind pioneer EOLFI.

Now BP’s aspirations, although thin on detail, have upped the ante with new CEO Bernard Looney in February committing the company to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, implying a fundamental shift over the coming decades to renewables and carbon abatement. Shell followed suit in April, also announcing a target of net-zero emissions by 2050, along with greater cuts to the carbon footprint of its products compared with previous announced goals.

While the coronavirus pandemic presents a grave risk to near-term electricity demand, electricity price and on-time project deployment, the fundamentals remain in place for renewables to dominate energy capital disbursement once the crisis eases.

Speaking to investors March 19, Enel CEO Francesco Starace said Europe’s Green New Deal was “an ideal vehicle” for kick-starting economies stalled by the virus. In the meantime the company noted Chinese equipment supply delays of just 40-45 days, pushing deployment of 200 MW back from December 2020 to January 2021. Meanwhile, in a week almost devoid of positive newsflow mid-March, it was Total making headlines with two new energy plays in onshore and floating wind.

While sentiment among the oil majors is definitely changing, investments remain modest compared to the size of their overall capex. The International Energy Agency says investment to date by oil and gas companies outside their core business areas is less than 1% of total capital spend. “A much more significant change in overall capital allocation would be required to accelerate energy transitions,” it said in January.

In the same month Shell CEO Ben van Beurden said he “regretted” missing out on purchasing Dutch sustainable energy utility Eneco last year, outbid by a consortium of Japan’s Mitsubishi Corp and Japanese utility Chubu Electric Power Co in a Eur4.1 billion ($4.5 billion) deal.

Van Beurden said that to succeed in the competition the oil major would have “busted” its “new energies” budget, illustrating how competitive the market is for transition plays – and how cautious Big Oil remains when presented with a relatively modest stepout opportunity.

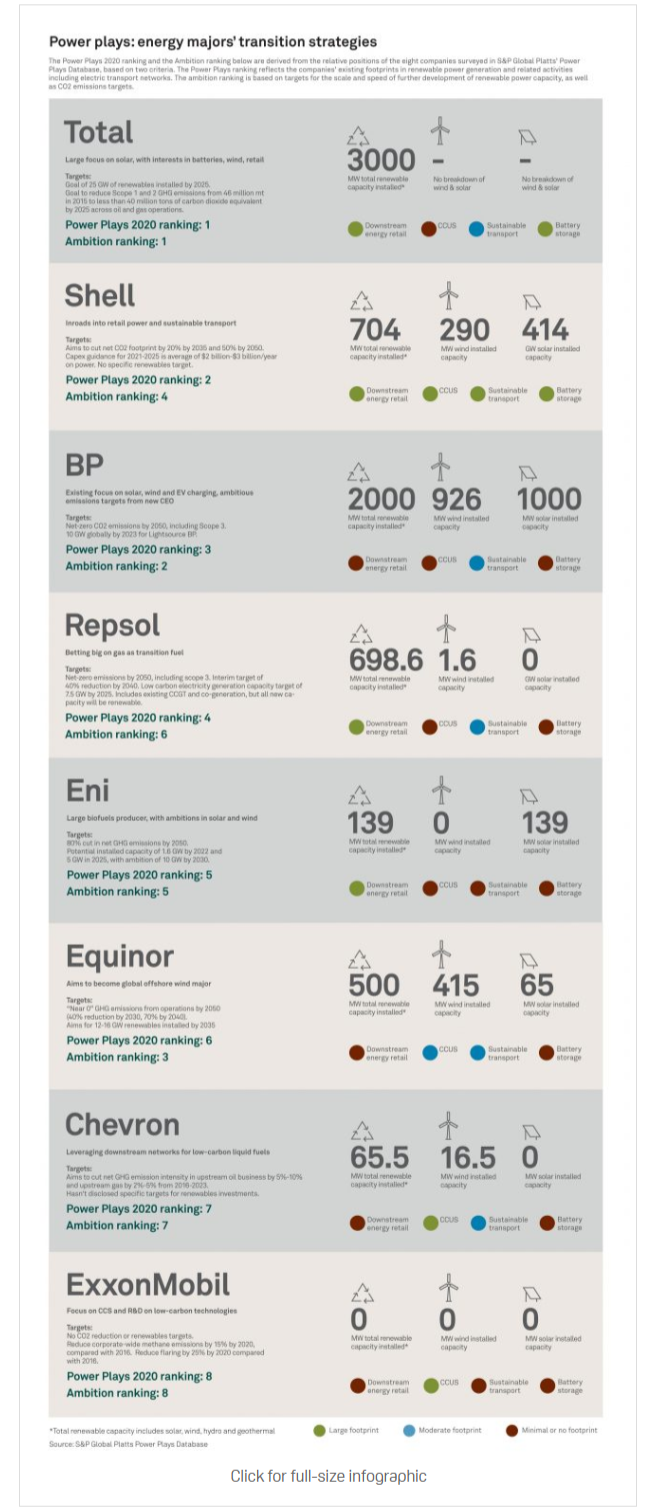

S&P Global Platts’ Power Plays Database, which tracks eight international oil and gas companies’ approaches to the energy transition, reveals several distinct strategies (see infographic). Broadly speaking, the six Europe-based majors surveyed have launched more enthusiastically into both renewables and the utilities space than the two US-headquartered companies.

Total and BP are clear leaders in terms of installed renewable generation capacity with 3 GW and 2 GW respectively. Repsol, with around 700 MW currently installed, has over 1 GW already in development across wind and solar, and a target of 7.5 GW of “low-carbon” generation capacity by 2025 – this includes existing CCGT and co-generation capacity, but new additions will be renewable, Repsol said.

Norwegian state-owned Equinor wants to have 12-16 GW of renewables installed by 2035, and can lay claim to being a sector leader in floating offshore wind, as well as carbon capture and storage technology.

The US majors ExxonMobil and Chevron have taken an approach that is more closely aligned with their traditional business models, focusing on improved efficiency, increased biofuels production and CCUS (carbon capture, utilization and storage). Venture capital initiatives and R&D investments are also a big theme.

Chevron has a small renewables portfolio of around 65 MW. This is geared towards serving its core oil and gas producing operations rather than constituting a separate business, CEO Mike Wirth said at Chevron’s analyst day in early March.

Chevron has invested $1 billion in CCS projects in Australia and Canada, and in 2018 launched a $100 million Future Energy Fund, to invest in “breakthrough technology.” The venture capital fund has targeted EV charging, battery technology and direct CO2 capture from the air.

ExxonMobil has been spending in excess of $1 billion/ year on R&D, and has tied up several agreements with universities, including in Singapore, the US and India, for research on biofuels and low emissions technology, among other areas.

ExxonMobil is targeting biofuels output of 10,000 b/d by 2025 (US biofuels production in 2019 was 1.09 million b/d, according to the US Energy Information Administration). The company has also invested heavily in CCUS, and says it has a working interest in approximately one fifth of the word’s total carbon capture capacity.

At an investor day in early March, ExxonMobil stressed that its approach to energy transition would build on its existing hydrocarbons and petrochemicals business, rather than depart from it radically. Key means to achieve this would be CCUS, biofuels from algae – which can be produced on a smaller land footprint than traditional biofuel crops – and new hydrocarbon-based structural materials to reduce emissions in construction and industry.

“Instead of replacing the world’s existing power generation system, we’re collaborating with others and researching more effective technologies to capture the carbon they emit,” said CEO Darren Woods. “Using existing infrastructure significantly lowers the cost of transition and could accelerate decarbonization in the power generation sector, particularly when you couple that with natural gas.”

In adapting and expanding their business models, international oil companies can follow two approaches to the energy transition that are not necessarily contradictory, according to Bassam Fattouh, director of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

“On the one hand, IOCs will continue to focus on traditional activities, increasing the efficiency of their operations and decarbonizing those operations to extend the life of their business and respond to government, societal and financing pressures. On the other hand, they need to develop new business models and de-risk low-carbon technologies extending beyond their core traditional activities,” Fattouh told S&P Global Platts in an interview.

“We are likely to see more divergence across companies in their approaches and in the speed of the transition, with some continuing to focus mainly on their core activities and traditional strengths in oil and gas while others accelerate the shift to lowcarbon technologies.”

Beyond the majors, a handful of smaller oil and gas companies have undergone more radical transformations. Denmark’s Orsted – formerly called DONG – has reshaped itself from a fossil fuel business to a pure-play renewables company in 10 years, reducing its carbon emissions by 86% in the process, while the UK’s Centrica is exiting oil and gas production in favor of an asset-light, retail customer-focused strategy.

Meanwhile, utilities that now consider renewables to be their core business are feeling the benefits after years of value destruction in their conventional assets. Last year the top 10 stocks in the utility sector rose in value by an average 49%, led by those with significant exposure to renewables. These are prime targets for Big Oil.

While the stock sell-off prompted by the coronavirus wiped gains off utility shares, a swift bounce for several in late March meant that, over a year view, these stocks remain on an upward trajectory with regulated businesses serving as something of a safe haven for investors.

And the underlying fact remains that as the share of green electricity in final energy consumption rises, so does the need for oil companies to hedge their E&P exposure, said Societe Generale’s utilities analyst Lueder Schumacher. “If you want to hedge upstream, do it by going after these disruptive technologies in renewables and associated infrastructure,” Schumacher said.

The financial markets are increasingly seeking exposure to renewables as the energy transition challenge escalates, so why not oil companies? Eni, Total, Repsol and Shell already have a sizable presence in the downstream retail sector. “The big stocks in the utilities sector are small fry compared to the oil majors,” Schumacher said.

And while renewables generation assets are currently favored above transmission networks, growth in infrastructure over the next two decades “is expected to be massive,” he said. “We are just at the beginning of the energy transition.”

Big oil companies reference lower returns as a barrier to investing more heavily in the increasingly competitive world of renewables, according to Mark Lewis, Global Head of Sustainability Research at BNP Paribas Asset Management.

“The biggest block on these companies moving into renewables is the so-called profitability gap,” Lewis said.

The oil majors traditionally expect returns of 15%-20% from upstream investments. “For renewables the return is 5% to 10%, at most 15% with clever financial engineering. Your average oil executive is saying, why should I bother?” Lewis said.

The oil sector is, however, “completely missing the point in the assumption that because it made 15%-20% before, it can carry on making 15%-20%. Those returns were only possible because there was no competition,” Lewis said.

Only now are oil analysts waking up to a comparison with the utility sector, where for a long time executives argued renewable energy projects would end up as stranded assets once subsidies were withdrawn.

“How ironic then that all the stranded assets on utility balance sheets ended up being conventional assets, impacted by renewables in terms of market share and value of electricity,” Lewis said.

Now the emerging market for electric vehicles is being fed increasingly by renewable electricity. “The oil industry is unused to dealing with this sort of competition, I don’t think they can see how quickly things might change,” Lewis said.

Climate is the existential theme everyone has been focusing on, “but what people miss about renewables is the decentralization theme, reducing the barriers to entry,” he said. “The way costs are coming down, it is really only offshore wind that remains as a capital intensive activity for big energy companies.”

In 2006 wind and solar accounted for just 6%-7% of total German power production, but 100% of power demand growth, Lewis noted.

“Once renewables account for 100% of the growth component, that tells you the fossil fuel component has peaked and is going into decline,” he said. The profitability gap notwithstanding, investor pressure is building on the likes of BP, Lewis said. “Brokers think one of these companies is going to be make a big step-out transaction in the next two years,” he said.

Orsted, as the sector leader in offshore wind, is an obvious target, but the Danish government would likely block any takeover bid. “And Orsted would argue: we don’t need it, we transformed ourselves. Look at the multiples. Orsted is trading over 30 times earnings, I can’t see any oil companies trading at those levels,” he said.

An alternative view is that the IOCs could have a far more transformative impact on downstream power systems, following a disruptive model rather than behaving like – or simply acquiring – a large utility.

A report co-authored by OIES’ Fattouh last year, The Energy Transition and Oil Companies’ Hard Choices, suggests that IOCs could bypass the traditional utility model as they carve out a niche in the power sector.

Ventures into EV charging, the authors argue, could be “an entry point to decentralized energy systems… part of a strategy to become a virtual power producer (VPP) and to optimize the use of distributed energy resources.”

“IOCs are in good position to leverage their assets to extend to the business of power and EV charging, for instance by developing gas-to-power and developing their renewables business,” Fattouh told Platts. But he questioned the appeal of a significant move into the traditional utilities space for oil and gas majors.

“Utilities have a different business model and operate in a very regulated environment. It’s not clear what benefits such integration would bring to IOCs and whether shareholders would reward them for such a move,” he said.

Whichever path they decide to take, the strategies of this handful of companies could make a big difference given their generous R&D spending and venturing in pioneering technologies.

Even if the oil and gas majors steer clear of traditional utility business models, by helping to link up changing trends in transport, power distribution and low-carbon energy, they may end up wielding an outsize influence in the electricity systems of the future.

Big Oil faces an existential challenge in the decades ahead. Will it maintain focus as a sunset industry, cashing out its business model to grateful investors? Or, as is the case today, will it continue to reposition itself incrementally in sustainable fuels, EV infrastructure and sustainable energy markets?

Taking the Orsted “big bang” approach seems a big stretch for these huge companies. In the near term, it seems likely that we will see a more prudent accrual of start-ups. But in the mid-term, it would not be surprising if one of them seeks to differentiate itself from the pack with a step-out acquisition.

There is also the question of the impact the oil majors will have as they look to reshape their businesses, both in terms of the energy sector’s evolution and the global race to curb emissions and slow global warming.

Currently, not only are the low-carbon investments small compared to their overall portfolio, but the eight majors surveyed in Platts’ Power Plays Database are responsible only for a small proportion of global hydrocarbons production. State-owned behemoths such as Saudi Aramco and China’s CNPC are far more insulated from societal and investor calls to decarbonize.

The stance taken by ExxonMobil and Chevron, that divestments from fossil fuel assets simply shift the emissions problem from one company or country to another, reasonably suggests the need to look at the issue globally.

But it may also miss a bigger point: the pressure from governments and investors on producers of hydrocarbons is only going to intensify, and the recent behavior of the high-profile oil majors is simply the most visible symptom. Those oil and gas producers that stay on the sidelines and resist a bigger shift in model may find they have missed the boat later on.