Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

27 May, 2022

The gender balance at the highest levels of Latin American banks continues to tilt heavily in favor of men.

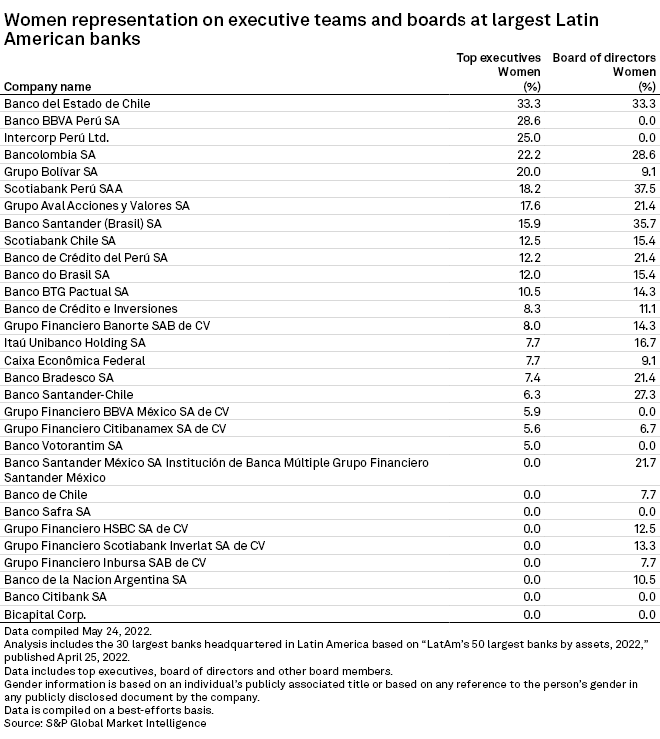

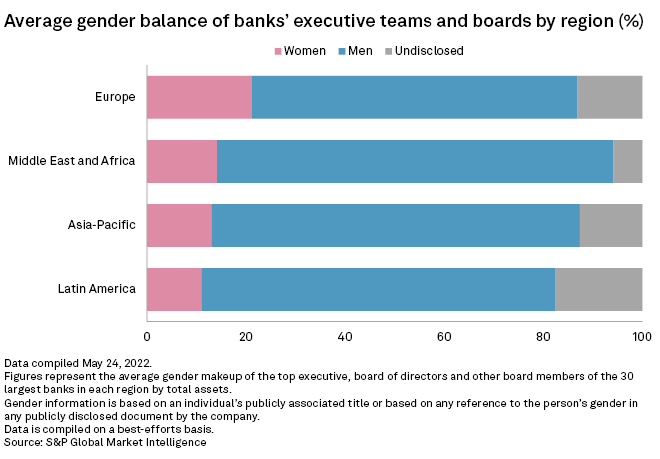

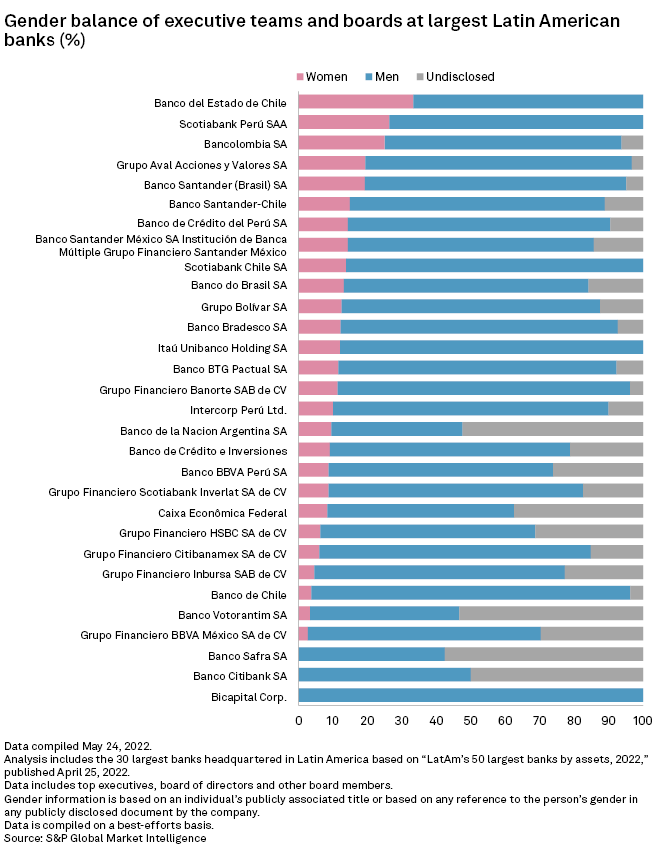

On average, women represent 11.14% of executives and board members at financial institutions in Latin America, according to data compiled by S&P Global Market Intelligence. In Europe, that figure is 21.27%. Asian financial institutions clock in at 13.13%, and those in the Middle East and Africa at 14.21%.

The actual percentage of women on boards and executive teams in Latin America could be slightly higher, taking into account that reporting the gender of employees is not as widespread as in other regions. In fact, Latin American financial institutions did not disclose the gender of 17.48% of employees in leadership positions. Men accounted for 71.39% of reported leadership positions.

The numbers of women in leadership roles continue to lag despite research showing that their inclusion brings benefits such as better financial performance and shareholder value and reduced risk of fraud and corruption, according to the International Finance Corporation. Quotas in some countries have helped increase numbers, but progress has been slow in conservative cultures where the argument is often made that there is a lack of qualified female candidates.

"I want to debunk what some people think it takes to get onto a corporate board. Whether it's in Latin America or in the U.S. or anywhere around the world, when I hear that we cannot find enough qualified, diverse candidates, my first response is you made the first mistake of assuming that it's about the qualifications," Cid Wilson, president and CEO of the Hispanic Association on Corporate Responsibility, said.

"We make the assumption that every board director is a qualified board director. I have a laundry list of unqualified board directors who got there either because it was a family connection or because they had old money and were able to invest," Wilson said.

Getting onto boards is about sponsorship and networking and not about qualifications, according to Wilson.

"If you look at the social construct of many Latin American countries, while yes, you have seen more women advance in terms of owning businesses and being able to succeed ... there is still that dynamic where women are often left out, whether it's country clubs, social gatherings, meetings where a lot of these sponsorship relationships begin to develop," he said.

Slow progress

"We have seen an increase in the last five to seven years, but we're not happy with the numbers," Daniel Aguiñaga, lead partner for corporate governance in Mexico at Deloitte. There is no rotation of directors whose tenures are long, and "boards are not open to changing directors or growing the board."

Deloitte's recent edition of its "Women in the boardroom: A global perspective" report shows that the number of women on boards in Latin America rose to 10.4% in 2021 from 7.2% in 2016. The number of female CEOs rose from zero to 1.6%. While most countries have progressed, the numbers remain unimpressive. In Colombia, 15% of board members are women, compared to 10.4% in Brazil and 9.7% in Mexico.

It does not help that Latin American cultures continue to carry a chauvinistic heritage that still sees women being needed at home, whether they have support or not, Aguiñaga said.

Change will come by way of quotas and will require government boards to monitor the process, according to Ruth Medd, executive chair at Women on Boards, an advocacy group. Stock markets should also have requirements, and interest groups should become more active, she said.

"We need to see more action from companies," with organizations changing their policies, Deloitte's Aguiñaga said.

Having women on boards should be a no-brainer, he said. Women make up 50% of the market and talent pool. They make the large majority of consumer decisions in families. By omitting them, companies are limiting their perspectives and opportunities.

Companies with at least one female director see better stock prices and return on equity, according to the IFC. With at least 30% of women in leadership positions, profit margins and rates of return on investments rise.

"It's a business case," Aguiñaga said. "It has been seen as, oh, it's because of equity, it's because of being a nice company. No. It's a business case discussion."