Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

18 Jan, 2022

By Brian Scheid

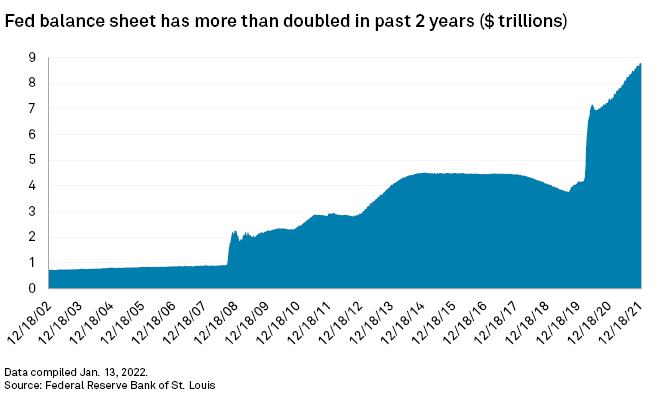

The U.S. Federal Reserve is moving to tighten monetary policy, ending its bond-buying program in March, with rate hikes to follow shortly after. That leaves central bank officials with a key challenge: reducing the central bank's nearly $9 trillion balance sheet far earlier than most market watchers anticipated.

The Fed balance sheet, fattened by the bank's $120 billion in monthly securities purchases since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, has grown to unhealthy economic levels, economists and strategists argue, with its sheer size distorting the bond market and threatening the future shape of the yield curve.

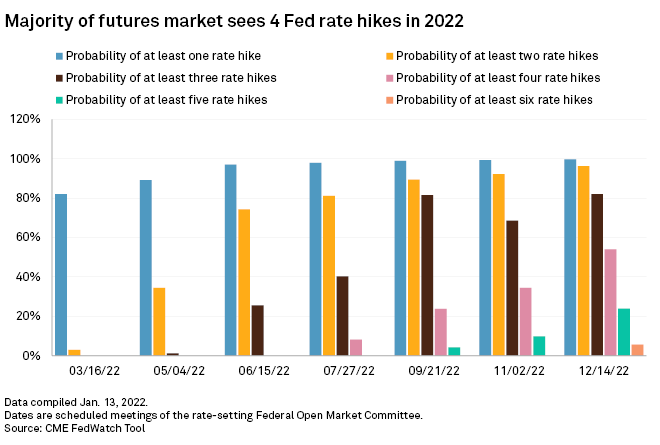

These effects could worsen as the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee readies three or more hikes to the federal funds rate in 2022, so the start of a lengthy balance sheet runoff is being quickly readied.

"I think because everything has been pulled forward and accelerated now, the spotlight has turned a bit to the normalization [of the balance sheet]," said Paul Gruenwald, global chief economist at S&P Global Ratings. "The timing is a surprise."

Quicker, higher, bigger

In its previous attempts to tighten monetary policy it imposed during the Great Recession, the Fed did not begin allowing some of its maturing assets to drop off the balance sheet until nearly two years after it first raised rates in December 2015. Now, the first rate hike may take place just days after the central bank's bond tapering process is done, and balance sheet reduction could be launched shortly after.

"The timelines are shifting dramatically," said Shahid Ladha, head of strategy for G10 Rates Americas with BNP Paribas. "The Fed may need to go quicker, go higher, do bigger increments. It's behind the curve on inflation, and it needs to catch up."

The Fed will likely reduce its balance sheet by not replacing bonds that mature, Gruenwald said.

In an attempt to curb soaring inflation, the Fed is expected to raise rates first in March, roughly two years after it initially slashed rates to near-zero and began buying bonds as part of an ultra-loose policy crafted in response to the pandemic.

Outsized risks

As expectations for multiple rate hikes have increased in January, Fed officials have ramped up talk of reducing the balance sheet which they see as a needed part of tightening monetary policy.

Keeping an "outsized" balance sheet while also raising rates could flatten the yield curve and push investors into riskier assets, Kansas City Fed President Esther George said in a Jan. 11 speech.

George said the Fed should "opt for running down the balance sheet earlier rather than later as we plot a path for removing monetary accommodation."

Maintaining such a large balance sheet skews the supply and demand balance of bonds in the market and keeps rates low, particularly at the long end of the curve, such as the 10- and 30-year yields, since the Fed has been purchasing longer-duration instruments.

If the Fed were to hike rates without reducing the balance sheet, fixed income strategists warn, the yield curve could be inverted, with short-term interest rates climbing higher than long-term rates, a sign of an approaching recession.

"The Fed doesn't have time to wait," said Althea Spinozzi, a senior fixed income strategist with Saxo Bank.

Consumer impact

Rate hikes will likely cause shorter-term rates, such as the 1- and 2-year Treasury yields, to climb more rapidly than longer-term rates.

A rise in short-term rates could put more pressure on consumer credit, increasing the costs of auto and student loans, said Tom Tzitzouris, head of fixed income research at Strategas Research Partners.

By launching the reduction in the balance sheet, the Fed could match the rise in short-term rates with a similar rise in longer duration rates.

As the Fed shrinks its asset holdings, longer-dated Treasury yields will rise, possibly reducing the Fed's need to hike rates.

"Given mortgage rates and corporate borrowing costs are more impacted by movements in 10-year yields than 3-month rates, the Fed funds target rate may not need to be increased as aggressively to get inflation under control," James Knightley, ING's chief international economist, said in a Jan. 13 note.

As fast as feasible

Fed officials discussed reducing the balance sheet at their December 2021 meeting, although views on the timing of that rundown were "diffuse," according to the meeting's minutes.

Over the past week, Fed officials have been increasingly vocal about reducing the balance sheet sooner rather than later.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell told the Senate Banking Committee Jan. 11 that balance sheet runoff would likely begin later in 2022. In a Jan. 12 interview with The Wall Street Journal, James Bullard, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, said the balance sheet reduction could take place as soon as this spring, after the first rate hike is imposed. That same day, Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said the runoff should take place "as fast as feasible."

Since the balance sheet talks were revealed in the minutes of the Fed's December 2021 meeting, shorter-duration Treasury yields, which move inversely to bond prices, have hit highs not seen since March 2020. The 5-year Treasury yield closed at 1.55% on Jan. 14, its highest close in two years. The 30-year Treasury yield also climbed, closing at 2.12% on Jan. 14 but failing to close above highs reached in October 2021.

The benchmark 10-year Treasury yield closed at 1.78% on Jan. 14, matching its highest close in about two years. The 10-year yield was trading above 1.84% on Jan. 18.

The yield curve has also flattened since the Fed signaled its push to tighten monetary policy. The gap between the 5- and 30-year yields, one measure of the curve's direction, was at 58 basis points Jan. 13, near its lowest point since March 2020 and down more than 100 basis points from its peak in February 2021.

The prospect

"We're already seeing some of the frothier sectors of the market start to deflate a little bit at the prospect of all this easy money drying up," Jones said.

Ladha with BNP Paribas said the Fed is also planning to reduce its balance sheet simply to prepare for the next crisis. If the Fed's balance sheet continues to climb beyond $9 trillion or even stays at that record level of U.S. GDP, then Fed officials' capacity to buy securities would be diminished if such a tool becomes necessary in the future.

"They might run out of runway," Ladha said. "They realize they need to get their toolkit back whilst they have the runway to do so."