S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

5 Apr, 2022

The Federal Reserve will likely forge ahead with its plans to hike interest rates despite wider credit spreads.

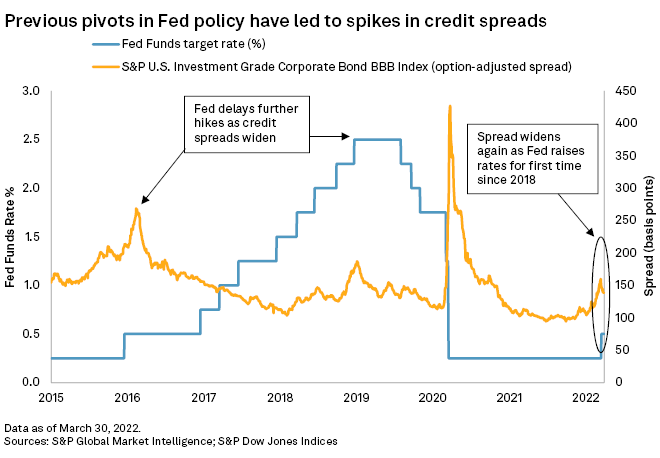

Markets have factored in the Fed's plans to push benchmark interest rates to nearly 2% this year and higher in 2023. The option-adjusted spread on the S&P U.S. Investment Grade Corporate Bond BBB Index rose more than 50 basis points from the start of the year to 160 bps in mid-March, when the central bank released expectations for the path of rates.

In the past, the Fed has paused rate hikes in the face of wider credit spreads, which translate to slower economic growth and higher borrowing costs for companies. This time around, the Fed has less reason to alter its course, given low bond yields, companies' healthy corporate balance sheets and a big reduction in corporate demand for debt.

"Although U.S. credit spreads have widened sharply this year across all sectors, financial conditions still remain far from restrictive territory," Rick Patel, portfolio manager at Fidelity International, said in an email.

Ongoing higher borrowing costs pose even greater challenges to heavily indebted and vulnerable companies sitting just above junk rating status. Nonfinancial corporations ended 2021 with a record $11.65 trillion in debt.

Fed undeterred

Aggressive rate hike plans for 2022 and 2023 come as the personal consumption expenditures index, the Fed's preferred inflation gauge, rose 6.4% year over year in February, the highest increase since January 1982.

In recent history, rising corporate bond spreads have dealt setbacks to the Fed's plans. The Fed halted policy tightening in early 2019 after corporate credit spreads widened by 50 bps, eventually cutting rates when the pandemic arrived, while a spike in spreads in the aftermath of a rate hike in late 2015 delayed further increases by 12 months.

Even with spreads widening this year, financing costs for companies remain historically low. The bar for the Fed to reconsider its plans is likely much higher, analysts at Morgan Stanley Research wrote in a March 22 note.

Funding costs would have to push much higher or markets would need to close for many participants to push the Fed from its currents plans, Patel of Fidelity said.

Russia's war against Ukraine has also narrowed spreads after a mid-March peak. The conflict and the Fed's rate plans are the key drivers of market performance, said Fraser Lundie, head of fixed income at Federated Hermes.

"We continue to see a bit of a tug of war between risk-off sentiment and inflation worries," Lundie said.

Higher debt, lower repayment costs

A large swath of companies is precariously positioned if higher borrowing costs become the new normal. Credit quality declined as companies racked up debt in the low-rate era after the 2008 financial crisis.

About $3.37 trillion in debt held by U.S. nonfinancial companies is rated BBB, just one rung above non-investment grade, or high yield, on S&P Global Ratings' ladder. Some 10% of total debt is flirting with downgrade with BBB- ratings.

A fall into non-investment grade can push up borrowing costs sharply. The yield on the S&P U.S. High Yield Corporate Bond BB Index was 4.84% as of April 1 as opposed to 3.75% for the BBB index.

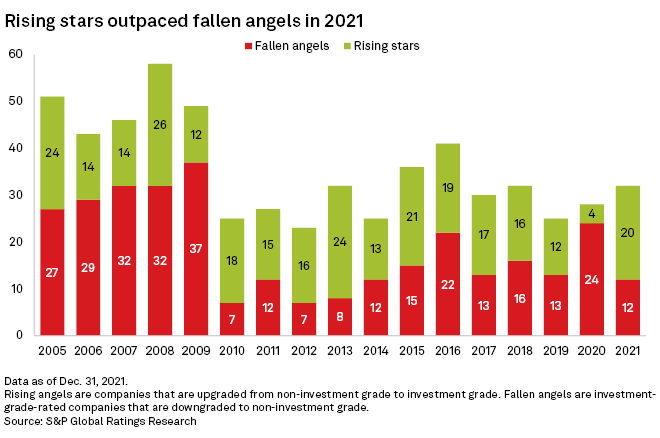

Las Vegas Sands Corp. was the most recent fallen angel, downgraded from BBB- to BB+ on Feb. 16, meaning its $10.45 billion debt is now non-investment grade.

The rate of fallen angels has been historically low in the last decade, with companies supported by access to cheap finance. After a mini-spike in COVID-19-affected 2020, the number of U.S. fallen angels fell to an eight-year low of 12 in 2021.

U.S. companies took advantage of low rates and quantitative easing in 2020 and 2021 to take on cheap debt and refinance old, costlier debt. In doing so, they reduced their leverage and pushed out the maturity wall of their outstanding bonds.

Companies issued bonds at record-shattering rates in 2020

Eventually, the mass of debt will have to be repaid or, more likely, refinanced at whatever are the prevailing rates. The good news is that companies have time on their side.

Typically, the maturity wall for non-investment-grade-rated companies peaks at four-to-five years out, but in 2021 that was extended until 2028, when $573 billion in debt is set to mature, according to Ratings.

This has contributed to a low expectation for defaults. Ratings has warned that a sharp widening of spreads could see the default forecast for the year at 6%, but their baseline is currently 3%, a historically low figure.

A key metric to watch for stability is the interest coverage ratio for the average U.S. company, Fidelity's Patel said.

The median interest coverage ratio — a measure of a company's ability to repay its debts calculated by dividing earnings before interest and taxes by the cost of its debt-interest payments — for nonfinancial companies rated investment-grade by S&P Global Ratings was 8.0 in the third quarter of 2021, according to the latest data published by S&P Global Market Intelligence. While this was down from 8.4 in the previous quarter, it was up from a pre-pandemic level of 6.0.

"Although this [interest burden] is increasing, it remains at levels close to historically low levels," Patel said.