Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

19 Aug, 2021

By David DiMolfetta and Sarah James

The U.S. Senate's $1 trillion infrastructure bill puts low-income Americans one step closer to a permanent broadband subsidy, but how that could force service providers to change their current low-income internet offerings remains to be seen.

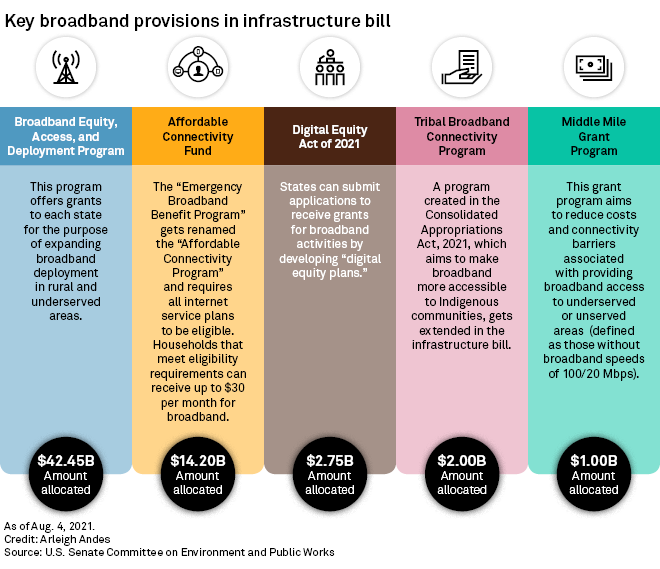

Of the $65 billion that the infrastructure bill allocates for broadband projects, $14.20 billion, or nearly 22%, is set aside for the establishment of the Affordable Connectivity Fund. The fund is an extension and reworking of the existing $3.2 billion Emergency Broadband Benefit Program, or EBBP, a subsidy program established during the pandemic to help low income households and Americans laid off during the pandemic stay connected to the internet.

While the EBBP was seen as temporary, the new fund is seen as more indefinite. Policy experts agree a longer-term broadband subsidy program will be a boon to consumers, especially in the face of the ongoing pandemic, as connectivity is critical for anyone trying to work or learn from home. But the differences between the original benefit program and new connectivity fund — both in terms of requirements around eligibility and promotional outreach — mean the new fund could have a greater impact on operators.

"I’m optimistic that this portion of the bill which received bipartisan support is necessary, but the devil is in the details," said Nicol Turner Lee, a senior fellow for governance studies at The Brookings Institution. "If we’re able to glean from lessons learned from the initial rollout [of EBBP], alongside some evidence-based research on what is the right sweet spot for broadband subsidies, I think we'll be in a better position."

Just the facts

The Federal Communications Commission's current EBBP provides eligible households with a monthly broadband service discount of $50, or $75 on tribal lands, and reimbursement for connected devices of up to $100 per household. Eligible households include those that have an income at or below 135% of the federal poverty guidelines, and those that qualify for programs like Medicaid or Lifeline, which provides a discount on wireline and wireless services for certain Americans with low incomes.

The Affordable Connectivity Fund, as envisioned by the Senate bill, is a bit different. It would offer a subsidy of only $30 per month, $20 less than that of the EBBP. While the new subsidy is smaller, eligibility requirements are broader, extending to homes at or below 200% of the federal poverty line.

"While the benefit is on paper dropping from $50 to $30, I think the net takeaway is that more people are going to be eligible for the program," said Brent Legg, executive vice president of Connected Nation, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit focused on broadband access.

To market, to market

Another major difference between the two programs — beyond the size of subsidy — is that internet service providers participating in the program would be required to run public awareness campaigns that highlight both the benefits of broadband and the existence of the connectivity fund.

This was an area that needed improvement in the original Emergency Broadband Benefit Program, said Jenna Leventoff, senior policy counsel at Public Knowledge. That program provided no funding or requirements around promotion, which may have limited adoption.

EBBP counted nearly 4.7 million enrolled households as of Aug. 15, according to the Universal Service Administrative Co.'s enrollment tracker. By comparison, USAC estimates that 33.2 million American homes are eligible for the Lifeline program, and any home eligible for that subsidy is also eligible for the Affordable Connectivity Fund.

To market EBBP, the FCC worked with local officials to share information, administering virtual public presentations, agency officials previously said in an email to S&P Global Market Intelligence. The agency also relied on earned media, with appearances on popular morning talk shows that target various demographic groups.

Leventoff said requiring promotions from providers will help, but the campaigns must appeal to consumers of all stripes.

"Even if people know about this program and they want to enroll, a lot of communities eligible for this might struggle to enroll. They may not speak English, or they may not even have internet," Leventoff said.

Eligible plans

Another difference between the two programs is that the new connectivity fund requires providers to apply the discount to any broadband plan a consumer wants to sign up for. This was not the case under EBBP, and it reportedly led to providers upselling their newest and most expensive plans to consumers.

"The reported shenanigans of some ISPs to upsell our most vulnerable consumers as a condition for using the emergency benefit have been addressed in this legislation," Jonathan Schwantes, senior policy counsel at Consumer Reports, said in a report on the legislation. "Allowing consumers maximum flexibility for how they wish to use their benefit will increase the effectiveness of this program."

This modification shows that legislators are paying better attention to the needs of consumers than in prior programs, Leventoff agreed.

One question that remains unanswered is whether the new subsidy will impact existing, voluntary low-income internet plans from broadband providers. Comcast Corp.'s XFinity, for instance, offers an Internet Essentials bundle for qualifying households that supplies 50 Mbps download speeds for $9.95 per month plus tax. Charter Communications Inc.'s Spectrum Internet Assist offers 30 Mbps downstream speeds for $14.99 per month, plus a $5 fee for in-home Wi-Fi.

"I think that service providers are going to be incentivized to tailor a service package that would meet the cost that’s available under this program, so I think we'll see a lot of service providers make a $30/month package available for a subscription that would be entirely covered by this program," Legg said.

Asked if he expects voluntary programs like Internet Essentials go away or become more expensive, Legg said, "I don’t think it means that programs like Internet Essentials go away, but now there’s this mechanism to pay for that service, and it likely means the criteria for what the service actually includes is probably going to get better."

The connectivity fund gives the private sector new opportunities to find a more competitive marketplace for their services, said Brookings' Turner Lee, but Congress needs to ensure that any low-income programs or offerings do not turn into "low-income alternatives" that push consumers into second-class tiers of internet access.

Comcast and Charter did not respond to requests for comment about the infrastructure bill or its potential effect on their low-income plans.

All told, the legislation still hinges on its ability to pass in the House, which is in recess until September.