Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

8 Mar, 2021

By Casey Egan

First came California with its sweeping data privacy law. Then Virginia followed suit. Now, the only question is which state might be next.

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam signed a sweeping piece of consumer data protection legislation into law this month, making Virginia the second state to pass a comprehensive data privacy law, according to privacy experts. The law, known as the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act, gives consumers the ability to access, correct, delete and obtain a copy of personal data. It also enables consumers to opt out of having their personal data processed for targeted advertising purposes.

The new law marks the latest chapter in an expanding patchwork of state actions on privacy. Tech groups have warned that each state passing its own rules and regulations will only create uncertainty for companies and consumers alike. As a result, the tech industry has repeatedly pressed Congress for a blanket federal solution. After passage of Virginia's law, Facebook Inc. called for imminent action on Capitol Hill, writing in a March 4 blog post that it hopes the new law, combined with proposals in other states, "will serve as an impetus for Congress to pass a comprehensive federal privacy law this year."

A tale of two laws

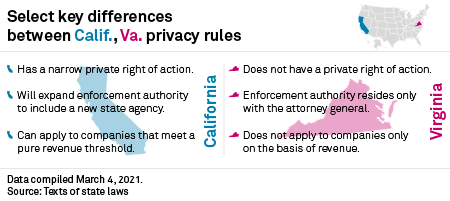

Virginia's new law is similar in many ways to 2018's California Consumer Privacy Act, but still differs in key respects.

CCPA brought a range of new privacy requirements to compel companies across industries — including major tech companies such as Facebook and Alphabet Inc.'s Google LLC — to give consumers more access and control over their data. Among other provisions, the CCPA gives consumers the right to opt out of having a business sell their personal information to a third party. The law, which has since been expanded by the California Privacy Rights Act, also lets consumers know why a company wants to collect their data, among other provisions.

Jason Gavejian, co-leader of the privacy, data and cybersecurity practice group at the law firm Jackson Lewis PC, said that from his perspective, one of the "most significant differences" between the CCPA and the VCDPA is that the Virginia law does not provide for a private right of action in the event of a data breach impacting personal information, while California's law does.

A private right of action can give private citizens the right to sue, rather than the government.

Under Virginia's law, the state attorney general is given exclusive authority to enforce the law, which is set to become effective Jan. 1, 2023.

"[In] Virginia, individuals would not be able to pursue their own civil claims under the law," noted Michelle Cohen, practice group leader for the data privacy and cybersecurity group at the law firm Ifrah Law PLLC, in an interview. "It would have to come from the attorney general's office enforcing it," she added.

Other key differences

Alan Friel, deputy chair of the data privacy and cybersecurity practice at the law firm Squire Patton Boggs, noted in a February report that the Virginia law excludes natural persons "acting in a commercial or employment context" from its definition of consumers, largely making business-to-business data and human resources data exempt from the law.

This differs from California, which currently offers only a temporary exemption for certain human resources and B2B data. Glenn Brown, a senior member of the data privacy and cybersecurity practice group at Squire Patton Boggs, said in an interview the exemption is set to expire in 2023.

Another difference between the two laws is that in Virginia, there is not a pure monetary threshold for applicability. Whereas California's law applies to any for-profit businesses that do businesses in California that have a gross annual revenue over $25 million, Virginia's law is a bit more complicated. It applies to anyone who conducts business in Virginia who controls or processes personal data of 100,000 consumers or more, or anyone who conducts business in Virginia who derives 50% of gross revenue from the sale of personal data and controls or processes the personal data of at least 25,000 consumers.

Because of the various differences, the Virginia law is perceived as more business friendly.

Tom Foulkes — senior director of state advocacy at BSA | The Software Alliance, a trade group that counts Oracle Corp. and Microsoft Corp. as members — said the group was "particularly glad to see [the Virginia law] recognizes the different roles that different types of companies play in handling consumers personal data — and its creation of obligations that fit those different roles."

Other states on the move

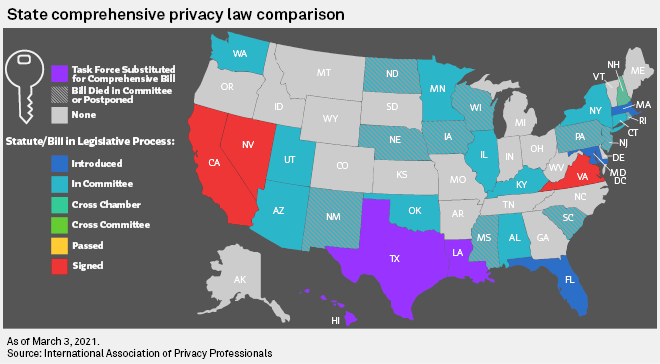

Virginia and California are not the only two states taking up privacy reform. In 2019, Nevada passed a limited privacy bill, which, among other things, requires privacy notices and opt-out options for users. Other states are considering their own privacy measures.

All told, the International Association of Privacy Professionals counts more than a dozen states where a privacy law has been introduced or is under review. In Washington state, for instance, a consumer privacy bill has passed one chamber of the state legislature.

Additionally, Gavejian says his firm is watching proposals in New York and Florida with particular interest.

In Florida, Gavejian notes that similar to California, one proposal in the state legislature provides for a private cause of action. The bill has the support of Gov. Ron DeSantis, who has said proposed privacy rules would "finally check these companies' [big tech] unfettered ability to profit off our data and ensure the protection of Floridians' personal and private information."

Now, Cohen wonders if the activity at the state level will compel action at the federal level.

"To me, the next question is — after how many states will Congress maybe decide to try to do something?" Cohen said.

So far, Congress has not yet coalesced behind a comprehensive bipartisan proposal.