Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

12 Jul, 2021

By Karin Rives

|

|

The prospect of sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere is gaining traction as policymakers and fossil-heavy companies ponder new ways to tackle climate change without upending the world economy.

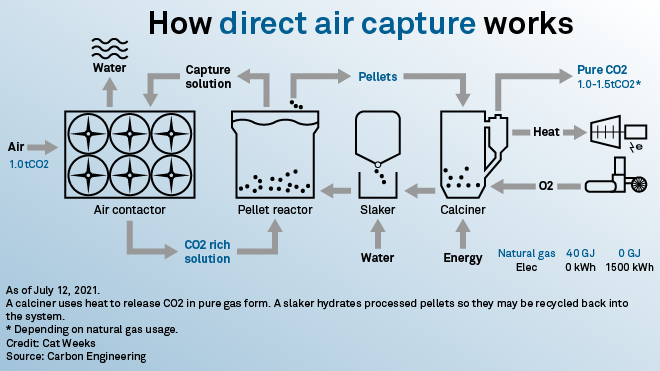

What may have sounded like science fiction a few years ago — deploying giant machines that draw in air and use chemicals to separate carbon dioxide from ambient air — is now getting closer to reality.

As of 2020, 15 relatively small direct air capture plants operate in the U.S., Canada and Europe, according to the International Energy Agency. But to use direct air capture, or DAC, to not just offset, but eliminate, large amounts of greenhouse gas emissions the technology must be powered by clean energy sources because it requires the use of so much energy, climate advocates say.

Power costs also remain a significant stumbling block to the broad deployment of the technology. Because carbon dioxide in the air is diluted and much less concentrated than what comes out of a smokestack, massive amounts of energy and money are needed to pull in just a ton. For instance, a liquid-solvent DAC system that captures 1 million metric tons of carbon annually will require up to 300 MW of uninterrupted power, according to a recent paper by Mihri Ozkan, a professor at the University of California, Riverside.

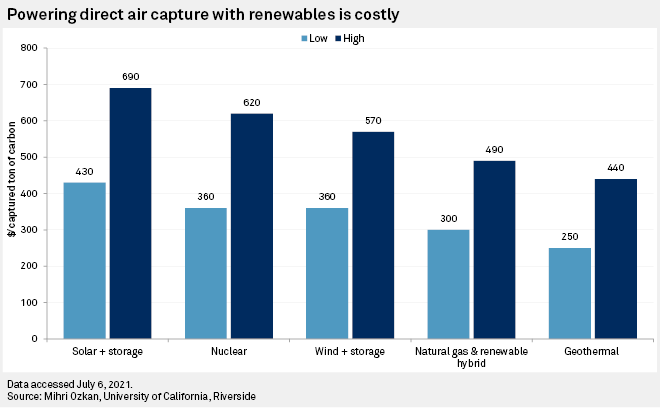

All of that renewable electricity is expensive. Ozkan estimated that capturing one ton of carbon from the air using solar and energy storage could run between $430 and $690, the most expensive renewable option. Powering DAC plants with nuclear energy would not be far behind, with costs for capturing a ton of carbon expected to range from $360 to $620. Geothermal energy would be the least costly source, as low as $250 per ton captured.

Others assert that like with most new technology, predicting the cost to deploy DAC on a global scale to reduce hard-to-abate emissions is difficult.

"We're early on, and there are lots of questions, but we also have reason to be encouraged that cost could be lower than that," Sasha Mackler, director of the Bipartisan Policy Center's Energy Project, said of Ozkan's cost estimates. "We're at the front end of the development cycle and engineering for DAC. What we're talking about is developing DAC at scale and what role it can play in the net-zero economy."

Big plants planned

Most DAC plants today are small facilities that produce carbon for drinks and other products. But a new project in Texas' Permian Basin backed by Oxy Low Carbon Ventures LLC, a subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum Corp., could become the world's first large-scale DAC plant.

The Oxy plant, to be built at a still-undisclosed site in western Texas, is expected to be up and running by the end of 2023, Vicki Hollub, Occidental's president and CEO, told analysts. Occidental, meanwhile, is planning to transition away from oil to focus instead on carbon management.

Hollub said during a recent earnings call that what people tend to miss is that DAC can be installed anywhere and still be effective because the winds balance the concentration of CO2 around the world. "That's what makes it possible to have direct air capture in the Permian and the [Denver Basin], the Powder River, Oman and hopefully in Algeria, too."

The Canadian company spearheading the DAC project in Texas, Carbon Engineering Ltd., recently teamed up with a company in the U.K. to build the country's first large-scale DAC plant in Scotland, expected to come online in 2026. The Texas and U.K. plants are each expected to absorb and trap up to 1 million metric tons of carbon annually. The company described its technology as akin to what plants and trees do when they photosynthesize, except for working much faster and with a smaller footprint.

Although the combined capacity of the two planned Carbon Engineering plants is far from the 10 million tons the IEA would like to see DAC plants capture by 2030, they are a good start, proponents of the technology say. DAC enthusiasts also believe that the high cost of running the energy-hungry plants will come down over time as renewable energy sources become ubiquitous and more plants begin to operate.

A 2018 analysis by Carbon Engineering founder and Harvard professor David Keith forecast that the company's plants could capture one ton of carbon for between $100 and $232 once the market has expanded.

Sensing an opportunity to offset their own greenhouse gas emissions and reach net-zero targets, corporations are also eyeing the emerging technology. Earlier this year, Carbon Engineering launched a new "carbon renewal service" that signed Canadian e-commerce company Shopify Inc. as its first customer. Shopify reserved 10,000 tons of carbon removal capacity from one of the large-scale DAC projects Carbon Engineering is working on.

Hollub said Occidental is having conversations with shipping companies, tech firms and airlines that are all potentially willing to pay several hundred dollars per ton to offset pollution.

The interest in DAC reflects a growing concern worldwide that climate change may be spinning out of control. The European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service reported April 7 that the U.S. experienced its hottest month on record in June, while Europe experienced its second-hottest.

DOE ramps up R&D

The U.S. government is also supporting DAC development. So far this year, the U.S. Energy Department announced more than $50 million in research and development grants for DAC projects. In addition, U.S. President Joe Biden requested $63 million for carbon dioxide removal research from Congress in the fiscal 2022 budget request, the first time that the White House included a separate line item for such emerging technologies.

The budget also included funding for a new DAC testing center to be housed within the National Energy Technology Lab.

"This would be an important step to really move DAC forward and to better understand a lot of those early-stage pieces of R&D," Shuchi Talati, chief of staff at the DOE's Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, told a recent Bipartisan Policy Center event. "For the first time, we have directed focus [on carbon dioxide removal] at DOE."

Adding to the growing excitement over DAC, supporters say, is that the technology is new and free of baggage from years of partisan squabbling over climate change. Proposals to extend federal 45Q tax credits for carbon capture as well as DAC, for example, have broad bipartisan support in Congress.

Increasingly, environmental advocates are also calling for a more broad approach to try to stem runaway climate change.

"Direct air capture may help with carbon emissions that are hard to avoid from aviation, shipping, and the concrete and iron-steel industries," Ozkan said in an email. "At this point, we need to exercise all types of negative emission technologies to avoid global warming that will endanger life on Earth."