Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

25 Feb, 2021

By Brian Scheid

The U.S. government bond market looks positively pre-pandemic. But that recovery is starting to pressure equities following a nearly year-long stock market rally.

On Feb. 25, Treasury's benchmark 10-year yield settled at 1.54%, up 16 basis points on the day and its highest close since Feb. 19, 2020. The 30-year yield closed at 2.33%, up 9 basis points on the day and its highest settlement since Jan. 9, 2020.

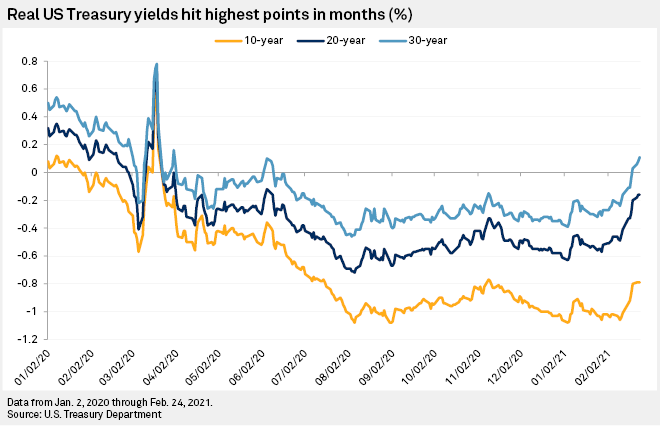

Late last week, the 30-year real yield, which measures the return on a long-dated bond after compensating for inflation, closed in positive territory for the first time since a brief break above zero back in June 2020. And the gap between short- and long-term Treasury bonds is the largest it has been in years, a sign of a coming economic expansion.

If bond investors are to be believed, a full-scale U.S. economic recovery is well underway.

The rise in yield rates, which move opposite to bond prices, reflects a few factors, said Gennadiy Goldberg, director and U.S. rates strategist at TD Securities, in an interview. These include increased optimism about a decline in coronavirus cases, an increase in vaccinations, and the expectation for a $1.9 trillion stimulus package poised for congressional passage, Goldberg said.

Negative real yields have been a boon for U.S. equity markets, which have hit record highs in the midst of the pandemic as investors flocked to better returns from stocks than bonds.

The recent rise in real and nominal yields, however, appeared to weigh on stocks Feb. 25. The S&P 500 settled down 2.45% on the day, and the Nasdaq Composite Index closed down 3.52%, its worst day since October.

"It is without a doubt that rising bond yields are starting to erode the attractiveness of stock markets," said Fawad Razaqzada, a market analyst with ThinkMarkets, in a Feb. 25 note. "So, if bond yields continue to rise, this could be bad news for stocks, as yield-seeking investors could make equally good or better returns by holding longer-dated government debt."

Financial conditions

As Treasury yields have returned to pre-pandemic levels, financial conditions and growth outlooks have done the same.

For example, the Chicago Fed on Feb. 24 reported that its National Financial Conditions Index was at -0.65, roughly where it was a year earlier. The index, which measures risk, credit and leverage conditions in money markets, debt and equity markets and shadow banking systems, has a negative value when financial conditions are looser than average and a positive value when conditions are tighter than average. The index spiked at 0.33 in early April.

But the decline from that spike was largely due to due to the Fed's accommodative monetary policies, including its bond-buying program, which Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said this week the central bank was not looking to change.

"It is likely to take some time for substantial further progress to be achieved," Powell told the Senate Banking Committee on Feb. 23. "We will continue to clearly communicate our assessment of progress toward our goals well in advance of any change in the pace of purchases."

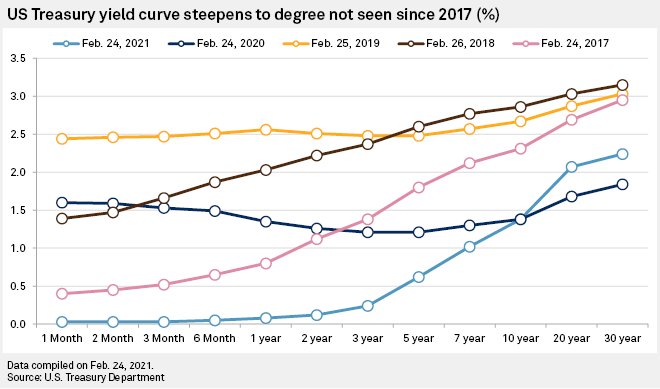

While Fed policy is boosting 10-year and longer yields up, it is also keeping shorter maturity bonds down, causing the yield curve to further steepen, according to Patrick Leary, chief market strategist and senior trader with Incapital.

A steep yield curve — when there is a large spread in interest rates between shorter-term Treasury bonds to longer-term bonds — often precedes a period of economic expansion, as investors bet that a central bank will be forced to raise rates in the future to tamp down higher inflation.

"The front end will remain anchored by Fed policy and the massive amounts of cash sloshing around the financial system," Leary wrote in a Feb. 18 note.

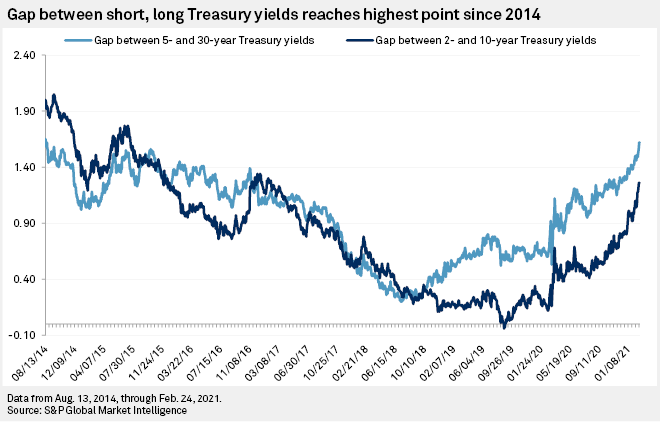

The gap between the five- and 30-year yields on Feb. 24 reached 162 basis points, the largest differential since August 2014. The gap between the two- and 10-year yields hit 126 basis points on Feb. 24, the largest gap since February 2017.

Despite the rise in yields, fixed-income analysts said they do not expect much of a sustained decline in equities nor a near-term shift in Fed policy.

While real 10-year yields have climbed by 27 basis points since Feb. 10, they remain "deeply negative and not far away from all-time lows," said Goldberg with TD Securities.

"We don't think the equity market will be derailed by this increase," he said. "In fact, expectations of more stimulus and improved growth projections should help equities remain robust in the near-term."

Michael Crook, deputy chief investment officer at Mill Creek Capital, said that continued, increasing yields will not cause the Fed to slow asset purchases and that rate hikes remain several years away. Fed officials want to avoid a market panic similar to the 2013 "taper tantrum," where Treasury yields spiked after the Federal Reserve indicated it would slow its quantitative easing program.

"They want to see longer-term real yields increase — along with inflation expectations — because it means monetary and fiscal policies are having the intended impact," Crook said in an interview. "You can also view higher real yields as implicit tightening, so the Fed's initial response should be to wait longer before removing accommodation."