Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

24 Feb, 2022

By Brian Scheid

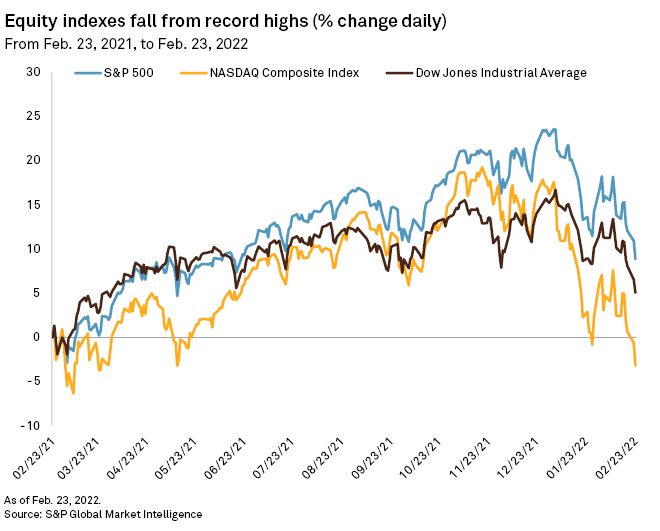

The S&P 500, already battered by soaring inflation and the Federal Reserve's plans to tighten monetary policy, tumbled into free fall early Feb. 24 as Russia launched military operations in neighboring Ukraine. That fall in equities is far from over, analysts said.

"Markets hate uncertainty and they are awash in it," said Paul Schatz, president of Heritage Capital. "Given the speed and veracity of the decline, we should see at least a short-term low very soon, as in the next few days or so, but the depth is not easily known just yet."

The large-cap index fell by as much as 2.6% in early trading Feb. 24, a drop of about 14% from Jan. 3, when the S&P 500 closed at an all-time high.

The headwinds facing equities — inflation, rate hikes and instability in Eastern Europe — began to emerge in late November, said Michael O'Rourke, chief market strategist with JonesTrading. Still, the S&P 500 went on to shatter all-time highs anyway, climbing about 4.4% from late November to its record-high settlement Jan. 3.

The same factors hammering stocks have since worsened. Inflation hit a 40-year-high in January, the Fed is considering a "supersized" rate hike in March, and Russia launched its offensive in Ukraine early Feb. 24.

"There remains a high level of uncertainty and no foreseeable conclusion to challenges regarding monetary policy or Eastern Europe in the immediate future," O'Rourke said.

Uncertainty worsens

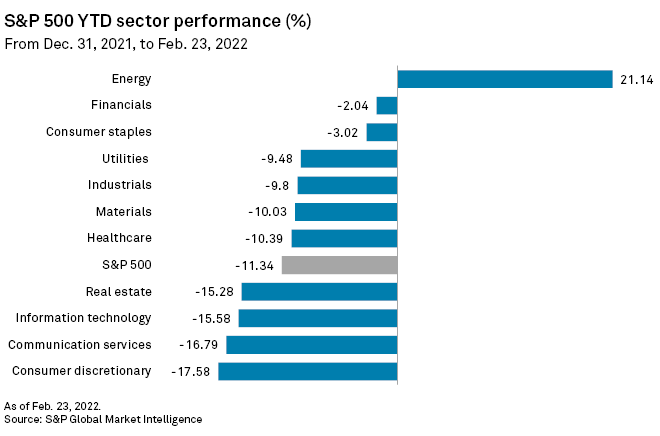

Every S&P 500 sector has fallen since the index's record-high settlement earlier in the year, except the energy sector, which has benefited from climbing oil prices.

The index could fall to the same levels in the early days of the pandemic when the Fed dropped rates to near-0% and began a bond-buying program, which has since pushed its balance sheet to nearly $9 trillion, O'Rourke with JonesTrading said.

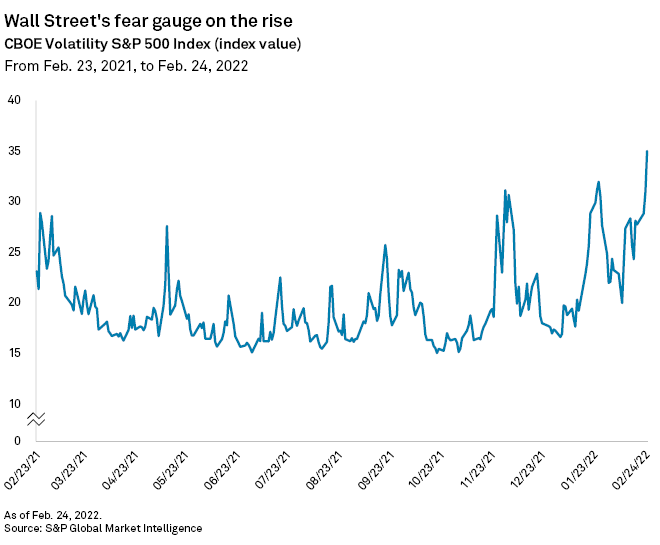

Uncertainty is on the rise and only getting worse, said Edward Moya, a senior market analyst with OANDA.

"Wall Street will have a hard time aggressively piling back into stocks until the big inflation question is answered and the risks of a Fed policy mistake of overtightening appears to be removed," Moya said. "Geopolitical risks have really thrown a big amount of uncertainty on when investors think inflation will peak and that is complicating everyone's forecast on Fed tightening."

On Feb. 24, the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index climbed above 35, its highest point since January 2021. The index is a measure of stock market volatility expectations based on S&P 500 index options.

Inflation and hikes

While the Russian military offensive may have jolted the market this week, other factors will exert more influence on the path ahead for stocks.

"Our view is the larger risk is the Fed's rate-hiking cycle and higher levels of inflation," said John Davi, founder and CEO of Astoria Portfolio Advisors.

The consumer price index, the market's preferred inflation metric, jumped 7.5% year over year in January, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Feb. 10. The January data for the personal consumption expenditures price index, the Fed's preferred inflation metric, will be released Feb. 25.

The rise in inflation boosted the odds that the Fed would raise rates by 50 basis points, rather than the more traditional 25 basis points, at its March meeting. Russia's military moves in Ukraine lowered the odds of a rate hike of 50 basis points to about 13% as of Feb. 24, down from as high as 94% on Feb. 10, according to the CME FedWatch Tool, which measures investor sentiment in the Fed funds futures market.

The Fed has delayed major policy decisions due to geopolitical uncertainty, but the Russian military offensive will likely not prevent the central bank from raising rates at their March meeting, Joseph Briggs and David Mericle, economists at Goldman Sachs, wrote in a Feb. 23 note.

"The current situation is different from past episodes when geopolitical events led the Fed to delay tightening or ease because inflation risk has created a stronger and more urgent reason for the Fed to tighten today than existed in past episodes," Briggs and Mericle wrote. "With some signs of problematic wage-price dynamics emerging and near-term inflation expectations already high, further increases in commodity prices might be more worrisome than usual."