S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

30 Sep, 2021

By J. Holzman

| A driver leaves U.S. Steel Corp.'s Gary Works manufacturing plant on June 20, 2019, in Gary, Ind. U.S. Steel has announced a massive investment into low-carbon steel production, and it is unclear whether existing production sites will be idled as a result. |

U.S. steel companies are injecting billions into new low-carbon steel production, a risk they hope will help them stay afloat as the world tightens up on carbon emissions.

The steel industry is one of the largest greenhouse gas emitters in the world, driven by its use of coal-fired blast furnaces, and it faces pressure from investors and world governments to reduce its carbon pollution. The largest U.S. steelmakers, buoyed by high domestic steel prices, made announcements in September to expand production into mini-mills, which swap out high-emission coal furnaces for electric arc furnaces. For steelmakers, the new technology offers an opportunity to beat out higher-emissions foreign competition and to avoid getting usurped by green steel startups.

But adding new domestic capacity creates the risk of generating too much steel in a market with prices artificially propped up by tariffs keeping out cheaper, dirtier foreign steel. An increase in production combined with an end to U.S. trade barriers could spell a major price crash down the road.

Steelmakers such as U.S. Steel, which announced new investments in mini-mills in September, reject that argument.

"Our goal is to build capability, not capacity, to get better, not bigger," U.S. Steel spokesperson Amanda Malkowski said in an email. "By accelerating our transition to more efficient mini-mill steelmaking, we expect to continue differentiating ourselves versus less-efficient capacity while improving our through-cycle profitability and lowering our capital and carbon intensity."

High prices give a cushion

U.S. steel companies have space to take a gamble, thanks to high domestic steel prices. The NYMEX US Hot Rolled Coil Index, an industry benchmark used to measure the value of steel contracts, hit $1,959 per ton on Sept. 22, a 226.5% increase from the prior year price of $600. That insulates the industry from the fluctuations in other inputs, such as the high natural gas prices that are bedeviling European steel producers.

On Sept. 16, U.S. Steel Corp. announced a $3 billion mini-mill project using electric arc furnaces that would be constructed in the Midwest. Just days later, on Sept. 20, Charlotte, N.C.,-based steel behemoth Nucor Corp. announced plans to build a $2.7 billion electric arc furnace steel plant, also in the Midwest.

"This mill is going to provide Nucor [with] a continued differentiated mix for ourselves as we move up that value chain and move into that space more heavily," Nucor CEO Leon Topalian said on a Sept. 20 call with analysts. Nucor did not respond to a request for further comment.

Bracing themselves

The companies are preparing for a world that demands they produce steel with far fewer emissions. The EU is considering a tax on imports based on the carbon intensity of those products, and, closer to home, President Joe Biden has made tackling climate change one of the centerpieces of his policy ambitions. This summer, nonprofits leaned hard on the president to advance sector-specific carbon reduction targets, and progressive Democrats are seeking to include "carbon polluter fees" on imports of steel and other commodities in their large budget reconciliation bill.

"I don't think any product made using coal can be climate friendly ... Our goal is to eliminate coal from the steelmaking process and shift to more sustainable material," Glenn Hurowitz, CEO of environmental group Mighty Earth, told S&P Global Market Intelligence in August. Hurowitz said Mighty Earth is currently in talks with automakers as part of a campaign to get them to buy cleaner steel products.

The companies also face potential technological disruption from heavily funded new startups. Boston Metal, which counts billionaire Bill Gates among its backers, is working on a no-emission steelmaking process, and Swedish startup H2GS AB is raising €2.5 billion to build a hydrogen-based steel plant in the northern part of that country.

They may be playing catch-up, as other steel majors have also announced electric arc furnace, or EAF, projects: U.S. steelmaker Steel Dynamics Inc. is building an EAF plant in Texas, and a joint venture between Luxembourg-based ArcelorMittal and Japan's Nippon Steel Corp. is funding AM/NS Calvert LLC to constructing an EAF facility in Alabama.

Danger ahead

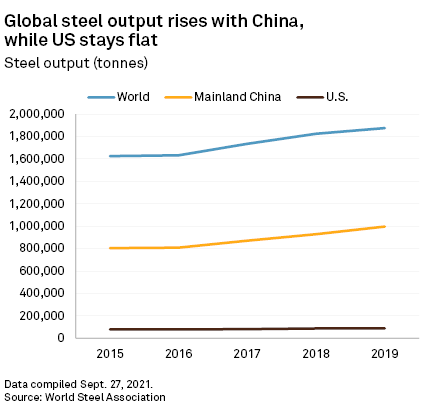

The U.S. steel industry only represents a small part of global steel production, which is otherwise dominated by China. But it has a captive domestic audience, and it has a history of expanding when prices go up, only to get caught short when the music stops.

"It seemed like they'd be pretty prudent about adding excess capacity," Moody's Investors Service analyst Michael Corelli said in an interview, adding that it is unclear whether the companies planning cleaner steel production will take any emissions-intensive output offline at the same time.

"The steel sector has a history when times are good of adding capacity and then regretting it later," Corelli said.

They also face a risk that the Biden administration may opt not to continue with the high steel tariffs imposed by the Trump administration. The U.S. and the EU are expected to have a path forward on negotiations to ease Trump-era steel and aluminum tariffs imposed on the EU by the end of 2021. Biden is caught in a bind, with the domestic steel industry and the union workers who helped carry him to the presidency on the one side, and end users like carmakers and builders seeking cheaper raw materials on the other.

The American Iron and Steel Institute, an industry group of U.S. steelmakers, sent a letter to Biden on Sept. 3 asking for "effective trade measures" to prevent a steel import surge from the EU and to work with the EU on the creation of carbon border adjustment measures to tackle climate change that would privilege cleaner steel producers.

Kevin Dempsey, president and CEO of the Institute, acknowledged the tariffs have "a shelf life" and that industry assistance is "not going to be permanent."

"The history of these types of measures ... They don't last forever," Dempsey said.